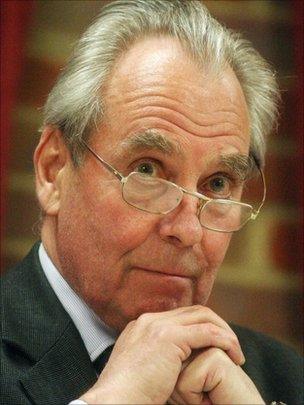

Profile: UKIP leader Lord Pearson

- Published

Lord Pearson did not enjoy his time in the media spotlight

Leaders of political parties sometimes like to give the impression that they took on the role reluctantly out of a sense of duty. In Lord Pearson of Rannoch's case you could actually believe it.

With his cut-glass accent and aristocratic connections, he was, in some respects, a throwback to an earlier era.

As a former Conservative peer and member of the House of Lords for 20 years, he was seen by UKIP's membership as the candidate with the gravitas and experience to lead the party into the general election after his friend Nigel Farage quit to fight for a seat at Westminster.

But he quickly discovered that being the leader of a political party, even a relatively small one like UKIP, is not like running a business or being a maverick, free-thinking backbench peer.

He often appeared ill-at-ease with the demands that the 24-hour media now places on politicians - the need to have an instant answer for everything and to sound like you know what you are talking about even if you do not.

His general election gaffe, when he confessed in an interview with the BBC's John Sopel that he had not read all of UKIP's manifesto, is not the sort of admission it is possible to get away with now. Perhaps it never was.

But, in contrast to previous UKIP leaders, who fretted about the party's image as a single-issue pressure group, Lord Pearson was not much concerned with expanding its agenda beyond its core campaign to withdraw Britain from the EU.

'Better politician'

He saw the party purely as a vehicle for achieving this aim and even offered to disband it if the Conservatives committed to a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty - an idea rejected by the Tories.

He also angered some in UKIP with his offer not to stand candidates against eurosceptic members of other parties at this year's general election.

His other main campaigning platform was to warn against the dangers of Islamic fundamentalism.

It came from the heart, but it was an area that the more politically savvy Nigel Farage had steered away from when he was in charge, perhaps recognising its potential to land UKIP with the charge of xenophobia, which he had worked so hard to shift.

Given all this, it is, perhaps, no surprise that he has decided to step down after less than a year as UKIP leader, admitting with characteristic candour that he does not "enjoy" or is "much good" at party politics, and the party "deserves a better politician than me to lead it".

But it would be a mistake to view him as someone who is not cut out for public life, or who lacks the stomach to campaign for what he believes in.

Before he became UKIP leader, the Eton-educated insurance broker had a reputation for not steering away from a public fight - the bigger the opponent, the better, it seemed.

In his time he had declared war on, among others, Lloyd's of London, the Home Office and Marxism.

Before last year's leadership election, Mr Farage described the peer, who was born Malcolm Pearson in 1942, as "head and shoulders above" his four rivals in the leadership contest.

And Jonathan Aitken, the former Tory cabinet minister, told the Daily Telegraph: "In my eyes, he has more moral and physical courage - and the remarkable tenacity that goes with those qualities - than anyone I have ever met short of an SAS commander.

"In my first week at Eton in 1956 I saw this tiny little boy on the football field, not only playing with skill but also tackling boys three times his size."

After school, Mr Pearson started a successful and lucrative career in the City.

Dissident groups

In 1964 he founded the insurance brokers Pearson Webb Springbett, which went public in 1984.

From 1975 he was involved in the so-called Savonita Affair at the insurance underwriters Lloyd's of London. His refusal to accept a claim involving cars supposedly lost at sea, but later found to be on sale on the Italian black market, led to reform and a new Act of Parliament.

During the 1980s Mr Pearson gave what he calls "financial and other assistance" to dissident groups in Soviet-dominated eastern Europe.

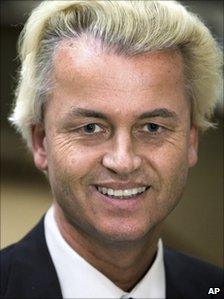

Lord Pearson brought controversial figure Geert Wilders to the UK

And, in 1990, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, one of his political idols and a vociferous opponent of Marxism, recommended him for a Conservative peerage, which he accepted.

While in the Lords, though, Lord Pearson's attitude towards the EU hardened.

He says it was his membership of the Lords EU select committee, from 1992 to 1996, which "led me to become a leading exponent of the case for the UK to leave the European Union".

In 2004, unhappy with his party's stance on the issue, he recommended that people should instead vote for UKIP in the European elections.

Lord Pearson lost the Tory whip and joined UKIP three years later, instantly becoming one of its best known figures.

But it was last year when he came to wider prominence as a politician.

Lord Pearson invited controversial Dutch MP Geert Wilders to show his allegedly anti-islamist film Fitna in the House of Lords.

However, Mr Wilders was turned away from the UK in February on the grounds that he could stir up public disorder.

Lord Pearson responded with outrage, saying the visit was a "matter of free speech".

Eventually the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal decided Mr Wilders could come and he did so in October last year, giving a press conference with the UKIP peer by his side.

But despite the headline-grabbing flair he demonstrated at this event, he found Mr Farage, a polished media performer, a hard act to follow as leader.

In his resignation statement, he said the party had exciting plans for the future but he wanted to spend more time on his wider interests.

He said: "These include the treatment of people with intellectual impairment, teacher training, the threat from Islamism and the relationship between good and evil - not to mention my dogs and my family."

The UKIP executive will choose a new leader next month.

For better or worse, we are unlikely to see anyone quite like Lord Pearson at the head of a UK political party again.

- Published17 August 2010

- Published17 August 2010

- Published29 July 2010