What has the Pope's visit achieved?

- Published

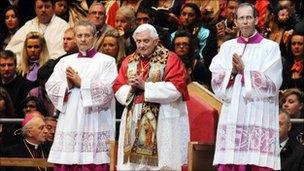

Thousands of people from across the UK travelled to catch a glimpse of the Pope

Popes do not just arrive in a country without knowing what they are about to encounter of course.

Catholic leaders in Scotland and in England and Wales have been briefing the Vatican for some time, and, no doubt, contributing to the Pope's speeches.

That is why Pope Benedict began to talk about sex abuse on the plane carrying him to Britain, an early acknowledgement of the Church's own failing in acting quickly enough to prevent it.

But the Pope did not make any reference to the biggest obstacle to healing the victims of abuse in his airborne press conference - the systematic covering up of abuse by the Church.

When he has referred to the way the Church's reputation was protected at the expense of children's welfare - in a letter to the Irish Church last March, the Pope seemed to be blaming local bishops.

Emotional meeting

So, when in Westminster Cathedral he used the phrase "all of us" in acknowledging the shame and humiliation brought by abuse, it seemed to be an admission of some corporate responsibility of the world-wide Church, and a step closer to what survivors' groups have demanded.

He also referred once again to sex abuse as a crime, an admission that the Church can no longer go on calling it a "sin", and by implication something it can deal with by internal discipline.

Then a few hours later Pope Benedict met five people who had been abused by priests, in what his spokesman Federico Lombardi described as an emotional meeting.

Organisations representing abuse survivors say actions will speak louder than words

Such papal meetings have worked well in taking the heat out of this festering issue in the past, especially in Malta earlier this year.

Someone who knew the five, said they were "not angry... but they have anger in them".

So was all this enough?

Organisations representing abuse survivors say actions will speak louder than words: they want files on abusing priests handed to the police.

The Pope is understood to have told the five people - three from Yorkshire, and one each from Scotland and London - that the Church was, among other things, ready to co-operate with the civil authorities in bringing abusive priests to justice.

But when new guidelines were published this summer, they fell some way short of the automatic reporting to civil authorities that happens under the system used by the Church in England and Wales.

A lot will depend on what the five people who talked and prayed with the Pope say.

Survivors' groups ask - reasonably enough - how they were selected by the Catholic dioceses who put them forward.

But the Pope is appealing not only to them, but to the general public, and so far the strategy seems to be succeeding.

Extensive television coverage has affirmed the Pope as a person of international stature - what other figure would get so much national attention?

It has also given him the opportunity to appear as the pastoral pope, not just as the dry, authoritarian, teacher.

The visit to St Peter's, the old people's home in Vauxhall, is a good example too of how he is managing to get his message across to a secular society.

In his speech there he said each person was valuable, and had their own worth and dignity even if they were very old and disabled.

The message was that this more or less universal view is central to Catholic teaching.

Moral code

In other words you do not need to go to church or sign up to Catholic dogma, to see the worth of a voice in society defending basic values.

In the same way as he asked children in Twickenham, "what sort of person do you want to be?" He is asking Britons more widely, "what sort of society do you want to have?"

The answer he is providing is that even a secular society needs to stay in touch with the basic, unchanging, moral code offered by religion.

Pope Benedict maintains that it is informed by natural law, or the fundamental nature of people, making it universal and timeless.

But the other thing the visit to Vauxhall allowed the Pope to do was possibly more important still.

The 83-year-old Pope joked about knowing the sorrows of old age, and outside greeted onlookers face-to-face.

The images may turn out to be worth more than any of his speeches, in wooing a sceptical public to Benedict's cause, and to him personally.