HMP Grendon: Therapy for dangerous prisoners

- Published

Lee Foye was given life in 2006 for the murder of 19-year-old Lauren Strachan

Lee Foye, who was imprisoned for killing a young mother, has been given a life sentence for killing paedophile Robert Coello in August 2010.

They were both inmates at Grendon - a very different kind of prison which tries to rehabilitate violent criminals through group therapy - and it was the first murder in its 51-year history.

"The hardest thing about Grendon is facing up to what you have done and what you have become."

That's the opinion of Noel "Razor" Smith, career criminal turned author, who spent five years at Grendon from July 2003 to May 2008 while serving a 12-year sentence for armed robbery.

Grendon is a unique prison - inmates volunteer to go there, they have control over the day-to-day running of their lives, and they can be voted out at any time by their peers.

It is still the only prison in Europe to operate wholly as a therapeutic community.

"A therapeutic community is a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 52-weeks-a-year commitment to analysing your behaviour in the context of a prison to try and gain insight and understanding into why you ended up in that prison," explains Professor David Wilson.

The leading criminologist is also a former Grendon governor and he is one of many experts who fear for the prison's future.

He feels the ongoing budget cuts are shortsighted, given Grendon's success. He says the two-year reoffending rate for prisoners who stay at Grendon for more than 18 months is 20%, compared with 50% for those serving time in conventional prisons.

'Diamond geezer'

Smith, who has 58 convictions to his name, volunteered to become a "resident" at Grendon after a road-to-Damascus moment in October 2001 when he was at the "top of the criminal tree".

"I was mixing with major villains, I was in a top-security jail and I was serving a life sentence," said the 50-year-old. "If you start out as a young criminal you kind of aspire, not to go to prison obviously, but to get into that company."

The father of four received the tragic news that his youngest son had died, but he was not allowed to go to his funeral because he was "too high profile and dangerous".

"I started to realise that what I had aspired to was absolute rubbish," he said. "I was the diamond geezer on the landings but I couldn't be with my family when they needed me most."

Going to Grendon was a big decision for Smith, who regards himself as an ODC (ordinary decent criminal) - their code of honour dictates that violence is reserved for other "wrong-uns" and the authorities.

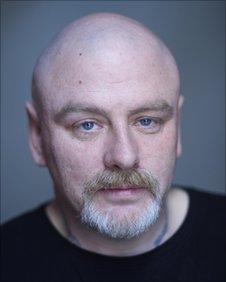

Noel "Razor" Smith was at Grendon for five years

"A lot of strange people go to Grendon," he said. "There's a pecking order in prison - everybody needs somebody to look down on. That would be the sex offenders, granny bashers, arsonists, and they were the type of people going to Grendon."

Smith's suitability was further tested on an induction wing before he was finally allowed to enter C-wing.

Three days a week, he would take part in small group meetings where residents would sit in a circle and analyse their own - and each other's - failings.

In addition, there was a wing meeting twice a week, where the groups would recount what had happened in the smaller sessions. Smith also took part in psychodrama - acting out scenes from his past - for two years.

Smith struggled with Grendon at first, with the respect he was shown, with the responsibilities he was given, and with mixing with child killers and rapists.

"I had spent my prison career finding these people and hurting them," he said.

What stopped him from "bashing their brains in" was hearing their stories and accepting that they too were at Grendon to try and change their behaviour.

Indeed, listening to sex offenders' accounts of their crimes left former Grendon prison officer Steven Heaven with post-traumatic stress disorder, and earlier this year he was awarded an undisclosed six-figure sum in damages.

Ever-decreasing budget

Prof David Wilson, now chairman of the charity Friends of Grendon, says the prison has never been without its detractors - to the "bang 'em up" brigade, it sounds like a soft touch - but for most residents it is much harder than being locked up in a cell.

He says the murder of Coello, a 44-year-old former bus driver who was serving life for raping a child, had brought the spotlight back on to Grendon.

During the trial at Luton Crown Court, the jury heard that Coello had been placed in a wing with prisoners who were not sex offenders because the prison was so full.

Patrick Mandikate, the prison's head of psychotherapy, admitted he was "uneasy" with the decision. "It was made clear to me in no uncertain terms that we needed to fill these beds no matter who was available."

Judge Foster said Foye had "manipulated the prison authorities to facilitate" his move to Grendon and he had chosen Coello as his victim "perhaps because he had been vocal about his own offending".

Prof Wilson argues the murder should not be allowed to undermine the work done at Grendon, which historically has had the lowest rate of violence within the entire prison estate.

"Make no mistake about it, Grendon is at a really difficult crossroads," he said.

"Its resources have been cut and cut and cut, and there comes a point at which it is no longer safe and we are very close to that point.

"If the government insists on cutting it further then I no longer see how it will be able to operate as a therapeutic community."

Smith has his own theories about the murder at the prison.

He believes the entry criteria have been "dumbed down" - which the Prison Service denies - and it is now easier to get in, because Grendon has to compete for residents as other prisons have opened therapeutic communities within their establishments.

More generally, it is an ever-decreasing budget that worries the Prison Officers' Association, the Chief Inspector of Prisoners and various academics.

After an inspection in 2009, external, the then Chief Inspector of Prisons, Dame Anne Owers, said it had "reaffirmed Grendon's remarkable achievements with some of the system's most dangerous and difficult prisoners".

She also said: "It was of enormous concern to find that cumulative financial efficiencies had begun to erode Grendon's capacity to deliver a therapeutic regime at all."

Criminologists Elaine Genders and Elaine Player first visited the prison in the late 1980s, and to celebrate its 50th anniversary they revisited in 2010.

Among their many findings, external, they reported fewer staff, groups cancelled on a regular basis, and residents spending more time in their cells.

They concluded: "One of the most significant factors affecting how Grendon functions as both a prison and a therapeutic community has been the Treasury-driven reductions in prison service expenditure."

A Prison Service spokeswoman said the Ministry of Justice needed to make savings of about £2bn by 2014/15 and this meant "tough financial decisions".

"The government is committed to a rehabilitation revolution," she said. "To help achieve this we need a fit-for-purpose prison estate, which balances the needs of offenders with the capacity of the public purse."

Smith, who was released in May last year, says that while he wanted to change his life, it would not have been possible without Grendon.

And the most important thing he learned there?

"Empathy. A lot of armed robbers tell themselves we don't have victims," he said.

"I had never really taken other people's feelings into account. When you think about what your victims must have thought, it is very hard to depersonalise them."

- Published15 November 2011