Time to spend more money preparing for colder winters?

- Published

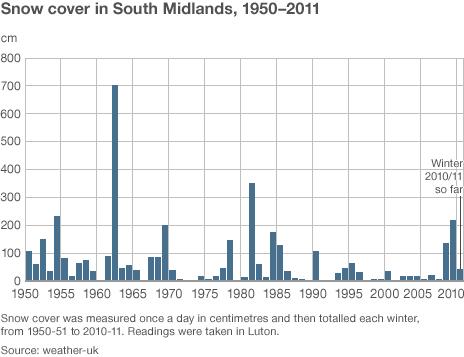

Snowy winters were commonplace in the 40s, 50s and 60s

December 2010 is every bit as cold and snowy as the worst December of the 20th Century - 1981 - and it could well turn out to be the coldest December since 1890.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the Transport Secretary Philip Hammond has asked the government's chief scientific adviser whether we might expect more severe winters in the coming decades, and whether we ought to invest in more equipment to keep our infrastructure moving during months such as this one.

The first thing to say is that it is essential to place current events in proper historical and scientific contexts.

The last three winters have appeared to be cold and snowy only in comparison with the relatively mild and snow-free winters of the last two decades.

Were we able to pick them up and transplant them into, say, the 1940s or 1950s or 1960s they would not have looked out of place at all.

In middle latitudes of the northern hemisphere our winter weather is controlled by the jet stream.

This is a powerful conveyor-belt of winds in the upper atmosphere which drives the weather systems that deliver our day-to-day weather.

In some years the jet stream is powerful and blows hard and true from west to east.

Here in Britain such a winter will be characterised by an endless succession of Atlantic storms, delivering frequent rain and wind, while temperatures remain resolutely above average.

In other years the jet stream is relatively weak, and like a sluggish river it will meander widely on its travels.

It still flows essentially from west to east, but it will stray deep into the sub-tropics, then into polar latitudes, and then back to the sub-tropics.

This winter, here in the UK, we find ourselves on the cold side of one of those meanders, and that means that the Atlantic depressions are heading across Spain and the Mediterranean.

This leaves the back door open for northerly winds to blow straight out of the Arctic, bringing severe frosts and heavy snow with them.

We can also see that the strong-jetstream winters and the weak-jetstream winters tend to cluster in groups.

Thus we have a series of mild and stormy winters, followed by a grouping of three or four cold and snowy ones, and then we are back to the mild and rainy regime.

We can easily identify the cold clusters in the last half century - 1962-65, 1968-70, 1978-82, 1985-87, and, to a lesser extent, 1995-97. What we don't know is whether the cluster we are in now is simply 2009-2010, or maybe 2009-2012.

I am often asked whether the last two winters mean that global warming has ended.

This is an important question, because it emphasises how much confusion there is about the difference between weather and climate.

Weather is caused by disturbances within the atmosphere, but climate is controlled by external influences, such as the distribution of oceans and continents, the extent of ice and snow-cover, variations in the amount of energy from the sun, and changes in the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

Climate is the underlying average, or if the climate is changing it is the underlying trend, whereas weather is the noise in the system.

We have always had huge day-to-day and year-to-year variations in our weather, and we always will do, and a couple of cold winters are no more evidence that climate change has stopped than a single summer heat-wave proves that global warming is happening.

What can be said with very little doubt is that, once this cluster of cold winters has finished, we will have another lengthy run of mild and rainy ones, and if we spend piles of cash on snowploughs and de-icing equipment, we may come to regret it.

- Published21 December 2010

- Published20 December 2010