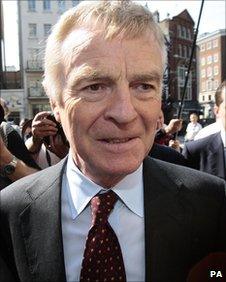

Max Mosley seeks reform of celebrity privacy laws

- Published

Max Mosley wants to end "ambushes" by tabloid newspapers

Ex-world motorsport boss Max Mosley is to go to the European court in a bid to reform celebrity privacy laws.

He will make a case for "prior notification", which would compel the UK press to go to celebrities or public figures at the heart of a story before running it.

The individual could then seek a court order to stop or delay publication.

A victory could mean the end for "kiss and tell" stories but critics say it could also damage serious journalism.

In 2008, Mr Mosley, the former president of the International Automobile Federation, won a famous victory against the News of the World newspaper.

A judge found that a story it had run about his sex life had invaded his right to privacy.

He was awarded £60,000 in damages, but everyone learnt the details of his sexual preferences.

'Ambush' prevention

Later, at Strasbourg's European Court of Human Rights, his lawyers will argue that money is not a sufficient remedy for the loss of a person's privacy.

They will say that newspapers should be made to notify the subject of a story before they run it.

That would enable them to seek a court order from a judge to stop the story being published.

Mr Mosley hopes to prevent what he sees as "ambushes" by tabloid newspapers.

He believes that the decision on whether to invade a person's privacy should be taken by a high court judge rather than a tabloid editor.

He told the BBC Radio 4 Today programme: "It's really the very simple thing that if a newspaper is going to write something about your private life, or something you might reasonably wish to keep private, they should tell you beforehand."

When asked if his proposal could hamper press freedom, Mr Mosley said: "I think that's the great fallacy.

Press freedoms

"The fact of the matter is, in 99 cases out of 100, if they are going to write something about someone of any great interest they will approach the person.

"What we are talking about here is cases where they don't come to you, they even perhaps publish a spoof first edition, because they know if they did you would seek an injunction.

"I think press freedom is absolutely vital and it has to be protected at all costs. It's the basis of a modern democracy - but that's a very different thing from newspapers concealing from you that they are going to publish something that's illegal."

Mr Mosley said he was going to Strasbourg on a "very, very narrow point".

And he said courts "will never give you an injunction if there is a public interest element in what the newspaper wants to publish".

Mr Mosley's case is the latest example of the clash between the right to privacy under Article 8 of the Human Rights Act, and the right to freedom of expression under Article 10.

Paper threat

If Mr Mosley succeeds, the government would have to act to impose a legal requirement on newspapers to notify people of the stories they intended to publish.

That would mean the number of so-called kiss and tell stories dwindling, but some fear it would also threaten serious investigative journalism.

Caroline Kean, from the law firm Wiggin, has represented many of the UK's leading publishers.

She was quoted in the Press Gazette, external as saying: "There will be a radically different press if he is successful with a lot of the colour taken away.

"We would see papers folding because they can't afford the legal costs. I hate to say it but it would imperil investigative journalism."

A judgement in the case is not expected for several months.

Jo Glanville, spokeswoman for Index on Censorship, which campaigns for freedom of expression, told the BBC changing the law could stop the media from publishing information which was in the public interest.

"There's something very worrying about it for press freedom in [Britain] because in a case perhaps like Max Mosley, it might appear obvious that this is, or was, an invasion of his privacy. In many cases it's not obvious.

"So what you might see is any individual who might want to protect their reputation, the reputation of their business, where the story might be very clearly in the public interest. It will allow them to stop publication of that story."

- Published29 October 2010