Did the New Cross fire create a black British identity?

- Published

The exact cause of the New Cross fire has never been established

On 18 January 1981, 13 black youngsters died in a London house fire which some feared may have been a racist arson attack, prompting a vocal outpouring of grief from Britain's Afro-Caribbean communities.

Thirty years on, what is the legacy of the New Cross fire and what does it tell us about changes in British society?

Yvonne Ruddock's 16th birthday party was supposed to be a happy occasion.

But instead of celebrating her young life, it marked the end of it.

And she was not alone - 12 others perished and they were all aged between 14 and 22.

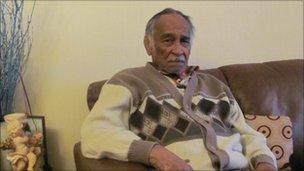

One of them was George Francis's 17-year-old son, Gerry.

Time has not proved to be much of a healer. His voice cracking with emotion, he recalls the "bright young man" who had been the youngest of his four children - the "baby of the family".

"It changed my life immensely. I used to think life is what you make it. After the disaster, I changed. If life was what you made it, my son wouldn't be dead."

The blaze at 439 New Cross Road was greeted not only with sadness at the lives lost, but also anger at the perceived indifference of the police investigating the cause of the blaze in the aftermath of rumours that it might have been a racially motivated arson attack.

That suspicion arose from the fact that the part of south London where the blaze occurred was, at the time, a National Front stronghold where arson attacks had been threatened against members of the black community.

In addition to the backdrop of simmering racial tension, many within London's Afro-Caribbean communities were wary of the police due to their use of "sus" laws which allowed officers to routinely stop people on suspicion of wrongdoing.

George Francis lost his son, Gerry, in the 1981 fire

"When the fire occurred we weren't very happy with the police because we felt they were a bit slack," recalls Mr Francis, who is now 82.

"The police back then didn't push as hard as they should have done to get us an answer," says the bereaved father, although he praised the officers who conducted a second investigation, involving fresh interviews with witnesses and forensic analysis, nearly 20 years after the fire.

At the time of the fire, police investigating it argued that they did not have enough evidence or witnesses.

Despite the police investigation being reopened after 16 years and two inquests, the precise cause of the fire has never been established and nobody has ever been charged in relation to the blaze.

In 1981, in the immediate aftermath of the fire and amidst a backdrop of suggestions that it was started deliberately, a committee was established within days to voice anger at the authorities' perceived apathy.

It organised a march in London, involving about 15,000 black people.

The lasting legacy of the New Cross fire may be that it helped create a black British voice with a politicised identity.

Playwright and actor Kwame Kwei-Armah says seeing the peaceful march in television reports as a 15-year-old was a "formative moment" that resonated with him and provided an indelible image.

'Turning point'

"It was the first time I had seen black Britons participate in an organised demonstration that was that focused. It was very clear to me that we belonged to this society and were using the means and ways that mainstream society used to organise themselves," he says.

"I felt a sense of connection to their outrage and articulation of wanting to change the status quo to be treated better. That demonstration was saying 'Do something, treat us fairly'.

Yvonne and Paul Ruddock both died in the fire

"It was my first experience of us, as a black community, standing up as a community in that way. This was black Britain - the ones who only knew this country as home."

Professor Les Back, the author of several books on race relations and social cohesion including New Ethnicities and Urban Culture, agrees that the response to the fire marked a "turning point" in multicultural Britain because "black people spoke for themselves".

"It was a coming out in public that this [indifference to black lives] was not to be tolerated."

The sociologist lectures at Goldsmiths, University of London, which is only a few roads from where the disaster unfolded. He was an 18-year-old student there at the time.

Loss of young lives

"As a young white person it was a particular education being around those events. It was an exercise in humility - we could play a part in the struggle, but not co-opt it.

"The black community was speaking for itself."

A march attended by up to 15,000 people was held after the New Cross fire

He says the same road on which the fire took place was, in 1977, the site of a National Front march. And this atmosphere, he argues, helped to politicise the black community and energise their response when the police and media appeared indifferent to the loss of young lives.

He argues that now, at a local level 30 years on, "popular racism at street level has become muted because the geography and cultural demography of London has changed" to create a "mundane, everyday multiculturalism".

And, although this multiculturalism is more evident in London than other parts of the UK, he says the notion that ethnic minority communities were entitled to a voice triumphed over the racist ideologies espoused by far-right extremists in the late 70s and early 80s.

"The idea that you could have 'purified' white spaces and (kept) difference at a distance is simply impossible in today's world.

"And there can't be any discussion now about there being 'no black in the Union Jack' because black soldiers have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan."