Two decades on, battle goes on over 'Gulf War Syndrome'

- Published

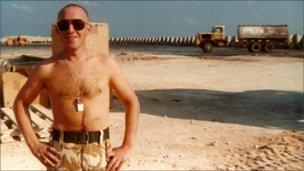

Veteran Kerry Fuller: "It would have been far better to be killed in action"

Every week, Kerry Fuller counts out his medication into a plastic pill box.

He fills the compartments with the 20-30 tablets he takes each day for heart problems and severe pain in his muscles and joints.

Formerly a keen hill walker, Kerry now struggles to walk more than a few dozen metres from his home at Dudley in the West Midlands without stopping for breath. Some days, particularly in cold weather, he is forced to stay indoors because of crippling pain.

Twenty years ago this weekend, coalition forces began the air campaign to force Saddam Hussein's Iraqi troops out of Kuwait.

As Operation Desert Storm got under way, Kerry Fuller was a senior aircraftman with the RAF Support Helicopter Force stationed at Al-Jubail in Saudi Arabia.

As part of his pre-war preparations he was given around a dozen vaccinations to protect him in the event that Saddam Hussein's forces used chemical or biological weapons. Within a week Kerry was taken to hospital with chronic fatigue.

He returned to active service a few days later but the bouts of ill-health recurred. He was in hospital again with chronic fatigue within a year of returning from the Gulf.

At the age of 40 he suffered a stroke, which has left him with a mild stammer.

Kerry Fuller believes his deployment to the Gulf caused what has come to be known as "Gulf War Syndrome".

"We were used as guinea-pigs, knowingly or unknowingly," he says.

"Going to war didn't bother me but I didn't bank on being poisoned by my own side.

"Now, a lot of us feel it would have been much better if we had been killed in action and hadn't come back at all."

Unexplained illnesses

There is little doubt that some veterans developed unexplained illnesses following their service in the Gulf two decades ago.

Reported symptoms range from chronic fatigue, headaches and sleep disturbances to joint pains, irritable bowel, stomach and respiratory disorders and psychological problems.

Since his deployment to the Gulf ahead of the war, Kerry has suffered recurring ill health

Twenty years on, though, there is still disagreement over why rates of ill health are twice as high among Gulf War veterans than troops deployed elsewhere.

Campaigners and doctors also continue to disagree over whether Gulf War Syndrome actually exists as a medical condition unique to Operation Desert Storm.

Even estimates of the number of people made ill by their service in the Gulf vary widely. Official figures show that more than 1,500 people in the UK have claimed war pensions due to Gulf War illnesses but campaigners insist the true number of sufferers is many times higher.

In the years since Operation Desert Storm, theories over possible causes of ill health have ranged from vaccinations, depleted uranium used in armour-piercing weapons, organophosphate pesticides, exposure to nerve agents and the effects of inhaling toxic smoke from burning oil wells.

Psychological factors and battlefield stress have also been cited as possible factors.

Professor Simon Wessely is director of the King's Centre for Military Health Research in London and an adviser to the Ministry of Defence. He does not believe Gulf War Syndrome exists as a distinct illness.

Even so, he has no doubt that a significant number of Gulf veterans became ill as a direct result of their military service.

"The evidence is incontrovertible that there is a Gulf War health effect," he says.

"Something to do with the Gulf has affected health and no-one serious has ever disputed that.

"Is there a problem? Yes there is. Is it Gulf War Syndrome or isn't it? I think that's a statistical and technical question that's of minor interest."

The Ministry of Defence echoes Professor Wessely's view.

An MoD spokeswoman told BBC News: "We have long accepted that some veterans of the Gulf conflict are ill and that some of this ill health may be related to their Gulf service.

"The UK and the US have undertaken a substantial amount of research into Gulf veterans' illness. The research has indicated that there is no illness which is specific to Gulf veterans."

But some ex-servicemen regard this position as cowardly.

'Left behind'

"The MoD is afraid of being accountable," says Shaun Rusling from the National Gulf Veterans and Families Association.

"If they admitted there was such a thing as Gulf War Syndrome they could be open to compensation claims for medical negligence.

"I would like the present government to apologise to the servicemen and give them proper care and pensions."

Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of veterans have suffered poor health since the 1991 war

Sue Freeth, director of welfare at the Royal British Legion, says it is "inexplicable" that sick British veterans are not receiving the same acknowledgement and treatment for their illness as US veterans.

She said more money had been spent on research into Gulf war illnesses in the US than in the UK.

"We had hoped that once good evidence was found in the States, this country would have had the good grace to say 'that's good enough for us'. But unfortunately no government to date has been willing to do that," she told the BBC.

As veterans remember the 20th anniversary of Operation Desert Storm, it seems increasingly unlikely that sufferers like Kerry Fuller will ever receive a definitive explanation for their ill health.

"I don't think we're ever going to be able to take it any further now," says Professor Simon Wessely.

"Even if you gave me £10m [for research], I wouldn't know what to do with it.

"I think the only thing worth spending money on is trying to help those who are ill."