The Briton who sought justice for Sobibor

- Published

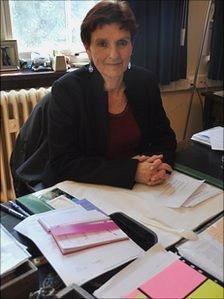

Helen Hyde is head teacher at Watford Grammar School for Girls

The conviction of John Demjanjuk is of special significance to Helen Hyde, who has long sought justice for her aunt who died at Sobibor.

She cannot forget her, not least because she carries her name.

The 63-year-old, who is head teacher at Watford Grammar School for Girls, had three members of her family killed at the Nazi extermination camp in May 1943.

She tracked the case of John Demjanjuk over its many months of painfully slow legal argument, and was in court in Munich for the opening of the trial and to hear the verdict.

Ukrainian-born Demjanjuk, extradited from the US in 2009, was convicted of aiding and abetting the murder of 28,060 Jews. The 91-year-old had denied the charges.

Mrs Hyde has twice visited Sobibor in Poland - still a "terrible place" - where her aunt Helen Neuhaus died, as did her son and husband, at the hands of Nazi guards, who pushed terrified crowds of people into gas chambers, driving them along using whips and bayonets.

Mrs Hyde said anyone posted to Sobibor was there "for one reason - you were involved in the killing. You aided and abetted that".

"If the argument is that he [Demjanjuk] was just a cog in the wheel, then the cogs are still human individuals with a mind of their own," she added.

"We're not machines and they were not monsters. They were just ordinary people accepting decisions."

Surviving daughter

Mrs Hyde's family were originally from Germany but some managed to scatter abroad as the Nazis' grip on power, and their anti-Semitic policies, grew stronger.

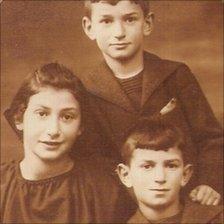

Two members of the family to escape the Holocaust were Helen's brothers Justin and Henry, who was to become Helen Hyde's father.

Henry went to South Africa in 1936, where his daughter was born. She emigrated to Britain in 1970 and became a British citizen soon after. Her crisp, clear voice hints at her South African past.

Helen Seligman - seen here as a child with her brothers Justin (top) and Henry - died at Sobibor

Her aunt Helen was a nursery school teacher and married Justin Neuhaus in 1937. He was running his family's leather goods business in Germany, but the couple fled to Holland a year later. Their attempts to reach the US by visa and England, via a fishing boat, had both failed so they moved, with their newborn son Peter, to the Netherlands.

While in hiding in Amsterdam during 1941, Helen Neuhaus had a daughter, Judith. The infant was later given away because of fears that her cries would betray her family. Judith Neuhaus survived the war and now lives in Israel.

But Justin Neuhaus, Helen and Peter were picked up by Nazis in the street in 1943 and deported to Sobibor, where they were murdered in the gas chambers. Helen, aged 33, and Peter, just short of his fifth birthday, died together while Justin, aged 42, was killed two weeks later.

Sobibor was one of three secret killing factories built by the Nazis in eastern Poland. In 18 months, a quarter of a million Jews were transported here and murdered in the gas chambers. Their bodies were incinerated, their ashes buried in pits.

Prosecutors said Demjanjuk had been a guard at Sobibor between March and September 1943 - meaning he would have been a guard at the time the Neuhaus family perished there.

"Did he have a choice?" asks Mrs Hyde.

"Yes he did. He could have refused. It would have been a risk to refuse but there's no great evidence that he would have been shot."

Thirst for justice

During her time in the courtroom she was only a few feet away from him.

"I had mixed emotions - I want to say I feel sorry for him because he's an old frail man, but I don't," she said.

"I don't feel hatred or revenge when I think of him. I feel frightened, because I'm Jewish and I'm frightened about Holocaust-deniers and I'm frightened of anti-Semites, and he might be one."

There were no living witnesses in Demjanjuk's case, but there were more than 30 people listed as joint plaintiffs - two camp survivors and others who lost relatives or their entire families. One of those plaintiffs was Judith, and Mrs Hyde also attempted to become a co-plaintiff herself.

The final day of the trial was one of great emotion for the Holocaust victim's niece, particularly when Judge Ralph Alt read out the names of victims.

"The judge was very careful to make no mistakes and did a superb job," said Mrs Hyde.

There was general surprise in court that the war criminal was being released pending his appeal, she added, but the main thing was Demjanjuk's conviction.

"Judgment was pronounced and Demjanjuk was found guilty of specific crimes," she said.

"He is 91 and is not going anywhere. He will be looked after by the German state. If somebody has to look after the man, let it be the German government."

Message for the future

In the main corridor at the Watford school, a notice board carries a display about Irena Sendler.

She saved 2,500 Jewish children by smuggling them out of the Warsaw Ghetto during WWII.

Mrs Hyde describes herself as an educator and says she cannot tell students that if they commit a crime and hide it for as long as they can, they will get away with it.

"I just feel that justice has to be seen to be done for those that died at Sobibor, because they can't do it," she said.

"Demjanjuk might be old and suffering but he's been surrounded by the best medical care available and lived to be at least 91. My aunt never had the opportunity to grow old."

The Nazi extermination camp of Sobibor was in the Lublin region of occupied Poland