Missed chances in Night Stalker case

- Published

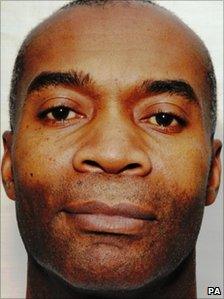

Grant was arrested in 2009 after an intensive police surveillance operation

Delroy Grant has been convicted of a series of sex attacks and burglaries across south London over a period of 17 years. Police think he could have had as many as 600 victims.

Grant's arrest in November 2009 has been described as a fine example of good old-fashioned policing. But Grant could and should have been caught 10 years earlier.

A member of the public spotted a car at a burglary in Bromley in May 1999, noted down the number plate and informed police.

The car was traced through driver records at the DVLA to Delroy Grant from south London.

But Grant was never arrested or even spoken to.

An Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) investigation found this extraordinary lapse was due to basic policing errors and a mix-up over identity.

When police got the name "Delroy Grant" from the DVLA, officers were distracted from what should have been a routine inquiry when a search of their own computer system, the PNC, revealed a listing for a man with a similar name.

Spoke to wife

By coincidence, his DNA profile happened to be on the national database. When it was compared to DNA samples left at various crime scenes there was no match.

Police then went to Delroy Grant's home in south London but their inquiries weren't thorough enough.

An officer spoke to his wife and she confirmed that the suspect car seen near the burglary did belong to them. But, inexplicably, police never went back to speak to Grant himself.

Grant was arrested at his home in Brockley, south-east London

In August 1999 Delroy Grant, from south London, the Night Stalker, was eliminated from police inquiries.

Grant went on to commit a further 146 offences after the blunder in 1999, including two rapes and 20 sexual assaults.

Commander Simon Foy, from the Metropolitan Police, said the force apologised for the "missed opportunity".

"We are deeply sorry for the harm suffered by all the other victims," he said.

Following the IPCC investigation, two detective constables have been disciplined by being given management advice.

In 2001, police received another potential clue that might have led them to Grant.

A caller to Crimestoppers said an e-fit of the offender resembled a man in a children's home, named Delroy Grant.

Police now say they do not regard this as a missed opportunity because the information they were given at the time was sketchy - the caller said the e-fit also looked like someone else.

Since Grant's arrest, officers have seen no evidence he was cared for or worked in a children's home and the home itself has been destroyed in a fire, making it hard to retrieve records.

But both near-misses, in 1999 and 2001, raise questions about Operation Minstead, the operation to catch the Night Stalker.

On the wrong track

Criminal profiler Professor David Canter, from the University of Huddersfield, said "incompetent policing" often played a part in serial offending.

"It's not really some sort of great criminal mind that carries out crimes over and over again without getting caught, it's really the lack of effectiveness, of the police, in being able to identify the individual especially in the early days when in a sense he's still learning his trade," he said.

One piece of information which appears to have put police on the wrong track during their inquiry was the suggestion that the Night Stalker rode a motorbike.

In a public appeal in 2006, Scotland Yard said this was one of his "significant characteristics".

Detectives say the motorbike theory emerged because one burglary victim heard a noisy, throaty engine roar after the offender left the premises.

However, police now say there is no evidence Grant owned a motorbike. Police say he did have an American Trans Am-type car, which could have made a similar noise.

During the police inquiry four experts were deployed to help catch the Night Stalker - two behavioural experts, one geographical specialist and a clinical psychologist.

Their work - although useful in informing police about the driving forces and likely background of the offender - did not advance the investigation significantly.

Arguably, however, what sidetracked police more than anything during their inquiry was the quest to identify the offender's ancestry.

DNA analysis showed that he originated from the Caribbean and that his relatives, going back five generations, were probably from the Windward Islands.

Although this helped narrow down the pool of potential suspects from 26,000 to 6,000 it did not get police any closer to Grant, who was in fact born in Jamaica and was not on the list.

Commander Foy defended this avenue of inquiry as "entirely legitimate" saying that it went to the "edge of science".

But in the end, Grant was caught by more basic police work: CCTV analysis of the suspect's car and an intensive surveillance operation involving 70 officers in the area where his offending began in 1992.

- Published24 March 2011

- Published24 March 2011

- Published24 March 2011