London 2012: The 1948 torch relay on a shoestring

- Published

Not the Duke of Edinburgh or athletics hero Sydney Wooderson, John Mark was the surprise last torchbearer in the '48 Relay

Plans are under way for a 2012 Torch Relay spanning the UK. But what happened last time London staged one?

It was no 70-day extravaganza and it involved nothing like the 8,000 torchbearers that will carry the Olympic flame around the UK in 2012.

But the London 1948 Olympic Torch Relay was greeted with wild rejoicing and a mobbing of the torchbearer, even when he, (and they were all 'he') ran on by in the dead of night.

Ahead of London's "Austerity Games", organisers wanted to stage a relay to "capture the imagination of the public and the spirit of the Olympic torch".

The organising committee, led by Lord Burghley, decided to continue the pre-war tradition started by the Nazi regime at the 1936 Berlin Games to set up only the second torch relay of the modern Olympic Games.

It had to be delivered on a post-war budget. Britain was struggling in 1948, rationing would be in place for another six years.

"Things were pretty grim,"" says Terry Charman, senior historian at the Imperial War Museum. "Although the war had finished in 1945, Britain was still a very impoverished country in 1948.

"A lot of wartime conditions were still in place. Not just food rationing but clothes rationing, everything was in short supply.

"There were few cars, the petrol allowance was so small. It was a very grey time and a very bleak winter in 1947 set things back.

"People would have resented the Olympics if too much had been spent, with Britain in the fairly parlous state it was in."

Britain could barely afford to stage the Games, let alone a torch relay, so its size, scope and the torch itself had to be affordable.

'British craftsmanship'

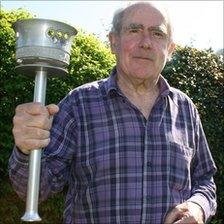

Hold a 1948 Olympic torch and its simplicity is revealed - fairly hefty, a plain stem topped with a wide cup that held the burner. Forties-style capital letters spell out "With thanks to the bearer" and the Olympic rings are punched out on the bowl.

Its designer Ralph Lavers was tasked to create something "inexpensive and easy to make," but still "of pleasing appearance and a good example of British craftmanship".

The torches were made of aluminium, which was relatively cheap, and ran on solid fuel tablets, except the one for the final leg at the opening ceremony inside Wembley's Empire Stadium.

It was stainless steel and housed a magnesium-fuelled flame designed to be easily visible by the watching crowds and cameras.

In 2012, the torch will cover the UK, aiming to come within one hour's journey of 95% of the population. In 1948 the domestic plan was less ambitious.

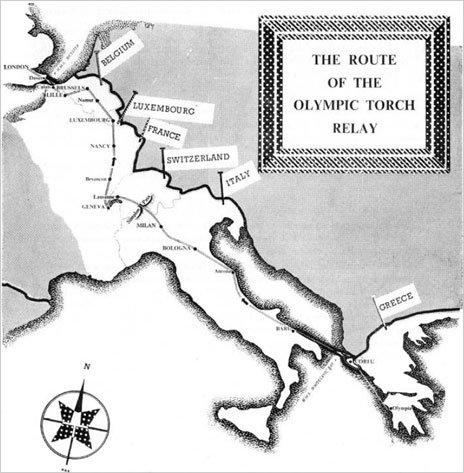

Instead, the relay had a wide scope on its European leg. It was a "Relay of Peace" starting from Greece, through Italy, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg and Belgium on its way to England.

It aimed to unite a Europe shattered by World War II and still in turmoil.

The torch pursued a quick path through an unstable Europe

The Games' official report, external tells how on 17 July in the ancient stadium at Olympia, the first runner, Greek Corporal Dimitrelis, "stepped forward... Laying down his arms and taking off his uniform, he appeared clad as an athlete and thus, having symbolised the tradition that war ceased during the period of the ancient Games, he lit his torch and set off."

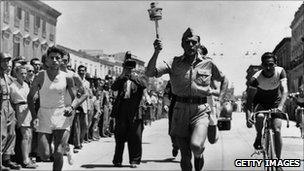

Symbolism aside, the "unsettled" state of Greece meant the girl first chosen to kindle the flame could not be there and the lit torch went straight to the coast and on to Italy - where it was carried through the country by the Bersaglieri, the Italian Army's jogging marksmen.

The torch crossed Italy in the hands of the Bersaglieri

But it made its way through Europe peacefully, frontier regulations were relaxed and people partied at the borders.

After years of stress, the report recalled, "a gleam of light, the light of a Flame, which crossed a continent without hindrance, ...caused frontiers to disappear, ...gathered unprecedented crowds to see it pass" and "lit the path to a brighter future for the youth of the world".

The torch's progress did not attract the kind of blanket coverage expected today. Tiny entries in the papers' News in Brief columns logged its 11-day journey towards England.

It didn't need the hype - when the torch arrived at Dover late on 28 July, 50,000 people welcomed it and a five-mile-long caravan of traffic followed the start of its overnight journey towards Wembley.

Reports in the local press and Janie Hampton's book The Austerity Olympics say the flame blew out for the first time as soon as it landed in Dover, only to be relit not by the back-up flames from Olympia, but by a cigarette lighter, and later on, by a firework.

Despite the shaky start, it was embraced. The relay was many people's only brush with the Olympic Games and a big enough draw to turn people out of their beds, in an era of few televisions.

In Charing, Kent, at 1.30am, 3,000 people mobbed the torchbearer; in Guildford, Surrey, "every available policeman" was needed to control the crowds.

"From the moment it arrived, it couldn't get through," says Olympic historian Philip Barker. "People were coming out at four in the morning just to see local boys, local athletes, carrying it past."

'Thrilling' role

On the A25, club runner Frank Verge, then 22, was waiting in the darkness to carry the torch on a two mile stretch between the Kent villages of Platt and Ightham.

His torch-bearing place was hard fought - he had taken on his older brother John in their club's eight mile run and ignored his shouts of "ease up, you'll burn out" as he broke away to win.

"They do say everybody has 15 minutes of fame in their life and I think that was mine," he says of the 4.03am to 4.17am slot.

Frank remembers hundreds of people lining the route...

"It was very exciting, the road was lined with what seemed like hundreds of people."

"We had just gone through six years of war and I think the Olympic Games stood for more because it was a different kind of life - everyone was happy.

"I'll never forget it, it was a great thrill."

Towards Surrey, Peter Finch was up at "the crack of dawn" to watch Arthur Galloway run a stretch through Westerham.

"It was lined right through with crowds of people," he recalls. "We stood three or four deep, shoulder to shoulder. I'd never seen so many people that early, it was a big event."

"I remember the flaming torch as it came through, he'd got it held aloft - he took it in his stride as you might say."

By the time the torch reached the penultimate runner, RS Ellis, 17, of Wembley County Grammar School, outside the Empire Stadium's opening ceremony, excitement was at fever pitch on a hot day.

Hampton's The Austerity Olympics describes how Ellis hid the unlit torch in his sweater for fear the crowds would pull it apart.

"Then, with the torch alight," he wrote, "I was off into the path cleared for me by six motor-cycle police."

'Seething mass of humanity'

He handed over to the last runner in the stadium, relatively unknown quarter-miler John Mark, whose athletic good looks were controversially chosen over the favourite-but-bespectacled miler Sydney Wooderson or the widely-expected Duke of Edinburgh.

...and says the memory is one he will keep for a lifetime

Days later, an offshoot of the relay would make its way from Wembley to Torquay for the start of the Olympic Regatta. There, local papers described "the whole sea front, a seething mass of humanity" to welcome the torch.

But that moment in the Olympic stadium was held up by commentators as an unforgettable climax.

The Time's athletics correspondent wrote: "A salute of 21 guns... and perhaps the most dramatic event of all occurred, the arrival of the torch-bearer".

Mark, he wrote: "Appeared amid the loudest cheers of the afternoon, many of the athletes on parade breaking their ranks and running to the trackside to watch him circle the arena.

"The bowl in which he kindled the flame stood on the peristyle... The flame shot up so fiercely and steadily that no one could imagine it going out until the appointed hour."