Analysis: Protecting the police front line

- Published

The visible front line is supported by others unseen by the public

When Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) told police chiefs that it wanted to define "the front line", one of them said the exercise would be as useful as medieval cosmology.

Despite the fact that only 22 of the 43 forces in England and Wales responded to the consultation, the HMIC has come up with its own map of the policing universe - and unsurprisingly it's not a simple diagram of blue-helmeted bobbies in one column and pen-pushing officers with creaking joints in the other.

Modern policing is massively complex - long gone are the days when almost all officers did similar jobs, the same shifts and spent their days shuttling back and forth between incidents. And that's where the problem comes in defining the front line - and the effects of cuts.

Sir Denis O'Connor, the chief inspector of constabulary, says quite clearly that some forces face a big challenge in making cuts without affecting the front line.

His definition of the front line is, by his own admission, both art and science - officers who are in everyday contact with the public and who directly intervene to keep people safe and enforce the law.

From that starting point, the HMIC argues in its report , externalthat the front line does not just mean officers visibly on the beat. In other words, it is not just those you notice - but those you rely upon in your moment of greatest need.

There is a complex eco-system of policing jobs all of which are inter-dependent and, in an ideal world, there to make sure criminals are caught.

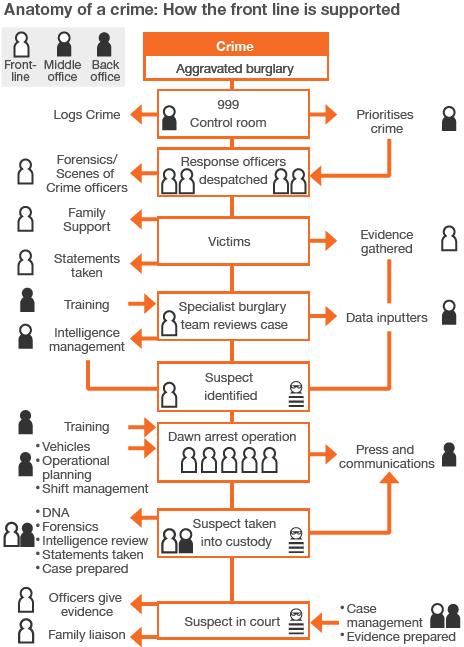

Anatomy of a crime

The graphic below shows just some of the many teams of officers who can be called on in a serious crime. In this example, the police receive a 999 call from a householder who has been attacked by an intruder in their home.

In many constabularies that call will be taken by a civilian in the control room rather than a sworn officer. The duty inspector would prioritise it and a team of response officers would rush to the scene. The scenes of crimes officers - the people in the white boiler suits - arrive to gather forensic evidence. In the HMIC's world view, they are part of the front line - but you only see them if you need to.

Other teams come into play - the family support officers, constables taking statements, officers gathering and managing evidence.

The specialist burglary detectives could be called upon. And they will inevitably look at their intelligence database - managed by people who are never on the streets. The definition of the front line begins, says Sir Denis, to "stretch back through the policing anatomy".

That stretched front line, argues Sir Denis, only functions when the middle office is there to do the things that directly support it.

And in turn, the "back office" jobs provide support services such as people working out shift patterns for the early morning arrest operation, management of vehicles and even training. You can see the full complex eco-system in the HMIC's table, external.

And that's the challenge: which of these posts can be removed without policing toppling over?

Money spent wisely?

Policing Minister Nick Herbert gave his definition of the front line to MPs on 7 March, external, saying it "includes neighbourhood policing, response policing and criminal investigation".

He argues that with a third of police resources going in the back and middle offices, efficiencies can and must be found.

He points to the wide disparity in visible front line policing between different forces.

By the HMIC's calculations, Merseyside performs best with 16.8% of visible officers available for duty at a given moment. Devon and Cornwall is at the bottom with 8.8%.

Lancashire comes mid-table close to the average of 12%. It has been running 62 reviews to cut costs - but has now warned the public it will lose 160 officers from front-line visible posts.

Chief Constable Steve Finnigan says on the constabulary's website there is one reason alone , externalwhy those posts are going.

He told the BBC: "Let me be really clear. With the scale of the cuts that we are experiencing, 20% over four years, when almost 85% of our budget is made up of people, we can do an awful lot of work around the back office, efficiency and bureaucracy, but we cannot leave the front line untouched."

But critics say that during Labour's decade of pouring resources into the police, chief officers simply failed to spend it wisely in modernising their forces. They question why more officers are available on Monday mornings than during the peak demand of weekend evenings.

Chief Constable Finnigan argues that it is simplistic to suggest the entire system is inefficient because the figures mask the nature of a 24-hour job.

Chiefs need at least five other officers for every one at work because of shift patterns, leave, training, secondments and sickness. In that context, having an average of 12% of officers available looks fair, he argues.

Efficiencies expected

Home Office ministers say that they want chiefs to drive efficiencies as hard as possible. They say that the 43 forces in England and Wales are operating 2,000 different IT systems that employ 5,000 people.

They say that some forces have successfully introduced more and more police staff into places like control rooms to free up officers to deal with crime.

But some of these changes pose delicate problems. Take control rooms. Some are largely manned by civilians. A handful of senior officers must always be available to make tactical decisions, such as authorising the deployment of firearms. That means those kinds of reforms can only go so far.

The Police Federation, which represents rank-and-file officers fears that more civilians in such posts damages "resilience" because it ultimately means fewer officers standing by their radios. They have also attacked forces for forcibly retiring officers who have completed 30 years of service, predicting a loss of vital experience.

But some critics of police practices say you cannot simply talk of numbers of officers alone - you have to look at how efficiently officers are allocated.

"The unspoken scandal of recent years has been the waste of police resources where sworn officers - a force's most valuable asset - have ended up on restricted duties or doing civilian jobs in offices," says Blair Gibbs, of the right-leaning think tank Policy Exchange, external.

"This has meant police officers being paid more to do jobs they shouldn't be doing, while reducing the number available to actually fight crime. As budgets fall there will inevitably be some reduction in officer numbers, but we are cutting from a high level so whether the public will even notice depends on where these reduction are made. In essence, it is always more important what police officers are doing, than how many there are - deployment trumps employment."

But the increased used of civilians in middle/back office posts can have an unintended consequence during cuts. Police officers cannot be made redundant - but civilian staff can.

Warwickshire Police Authority says it is asking for civilian redundancies and it will have to move scores of officers from front-line roles to support posts.

The HMIC says that many support posts need to be filled because they are simply not "disposable assets". If someone isn't putting the dots on the maps and entering the data, the officers have a lower chance of catching the prolific burglar.

Sir Denis O'Connor says: "These are the people who are building the cases, doing the analysis, mining the exhibits, making sure the vehicles turn up. They are all doing their bit - the front line only lands when the other bits connect up."

- Published30 March 2011

- Published18 March 2011