Lucas loses Star Wars copyright case at Supreme Court

- Published

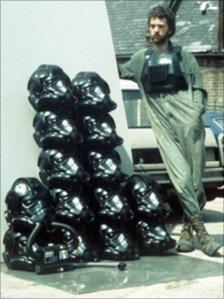

Mr Ainsworth recalls: "I made a prototype and Lucas said 'great, I'll have 50'."

A prop designer who made the original Stormtrooper helmets for Star Wars has won his copyright battle with director George Lucas over his right to sell replicas. The five-year saga, which ended in the highest court in the land, has stakes of galactic proportions.

For a man who has spent half a decade and almost £700,000 fighting the full force of a movie mogul's legal team, Andrew Ainsworth has refused to be weighed down.

He has had bailiffs at his door demanding $20m (£12m) and has defended the onslaught in the High Court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court - not to mention the US.

But like the iconic characters he helped create as a 27-year-old art school graduate - and which still surround him in the same modest workshop 35 years later - he has become battle hardened.

"You've got to decide right at the start, can you afford the downside?" he says.

Andrew Ainsworth explains how to make a Stormtrooper helmet

"And you've got to be able to live with it and be under no disillusions that if it all goes wrong, you're scuppered, you're bankrupt... I think if you're in a small business on your own you know the bottom line."

He says it is hard to accept when something you create is taken off you, and adds it has been a struggle because he went to court on a principle, against accepted wisdom.

The journey has certainly been long for the father-of-two, who has been selling his plastic composite helmets and body armour from his studio in Twickenham, south west London, for eight years now.

It was in 2002, when struggling to pay school fees, that he first sold a helmet and "bits and pieces" gathering dust on top of his wardrobe.

'Pandora's box'

To his surprise they fetched £60,000 at Christie's, leaving him in no doubt about their potential.

"The phone didn't stop ringing... I dug out the old moulds, cleaned them down and made a few helmets," he says.

The hard core fans recognised them as the real thing, he recalls, but by the time he had sold 19 or so to the US, so did Lucas.

Lucasfilm sued for $20m in 2004, arguing Mr Ainsworth did not hold the intellectual property rights and had no right to sell them - a point upheld by a US court.

But the judgement could not be enforced because the designer held no assets in the US, so the battle moved to the UK.

Although no paperwork was ever signed between Mr Ainsworth and Lucas, it was ruled there was an "implied contract".

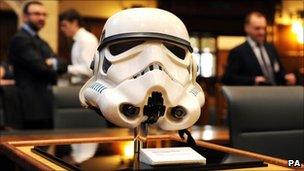

Nevertheless, the High Court rejected the multi-billionaire director's claim and the focus switched to design rights, specifically whether the helmets sold were works of art or merely industrial props.

If Lucasfilm could convince the courts the 3D works were sculptures, they would be protected by copyright for the life of the author plus 70 years.

If not, the copyright protection would be reduced to 15 years from the date they were marketed, meaning it would have expired and Mr Ainsworth would be free to sell them.

The High Court and Court of Appeal found in Mr Ainsworth's favour, and despite Lucas being backed by directors Steven Spielberg, James Cameron and Peter Jackson, the Supreme Court has now followed suit.

So, how did the young industrial design graduate, who experimented with plastic mouldings and made his own flares, land the Star Wars job in 1976?

Prop work on Superman, Alien, and Flash Gordon followed Star Wars

By chance and by knowing creative people on the fringes of the film industry, which made us cheaper, the 62-year-old says bluntly.

A puppeteer friend of his, Nick Pemberton, had been asked to make a clay mock up of the Stormtrooper helmets after meeting the then largely unknown George Lucas at Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire.

Mr Pemberton started the job, based on the original drawings by Ralph McQuarry, but had little experience of plastics, so handed it on to Mr Ainsworth saying "give me a drink if anything comes of it".

"I spent two days on it and made a prototype and Lucas said 'great, I'll have 50'," Mr Ainsworth recalls.

"As we moved into armour and got through the first shoot in Tunisia, the whole thing gathered momentum.

"There were lines of limos waiting outside for everything that came off the machines, they were that hungry for it."

As he fashioned Darth Vader's evil foot soldiers for a galaxy far, far away, he was blissfully unaware of the cultural legacy and legal pitfalls that lay ahead.

The young designer was paid £20 per helmet and £385 per armour - objects he sells today for around £500 and £1,000 respectively.

The Star Wars commission "on a handshake and word of mouth" also led to work on Superman, Alien and Flash Gordon.

Lucasfilm says the UK should not allow itself to become a "safe haven for piracy"

So what are the wider implications of the Supreme Court ruling?

For Mr Ainsworth, it means he is free to expand his business, but for George Lucas, according to Mr Ainsworth's lawyer Seamus Andrew, it opens a "Pandora's box" as anyone is now free to make the models.

He says other prop makers encouraged by the ruling may now come forward to take advantage of their own ingenuity.

The lawyer believes the director pursued his client so hard because his cage was rattled by the "authenticity of the product".

George Lucas has always argued Britain should fall in line with the rest of the world and offer full copyright protection to the works of art.

A Lucasfilm spokeswoman said: "We believe the imaginative characters, props, costumes, and other visual assets that go into making a film deserve protection in Britain. The UK should not allow itself to become a safe haven for piracy."

George Lucas and his Hollywood supporters also argued the ruling posed a "significant threat" to the UK film industry as film-makers would be deterred from using UK propmakers for fear of copyright infringement.

James Burns, who co-owns the UK's leading Star Wars fan site Jedinews, says he sides with Lucas on the debate about art.

"If you employ someone to design and sculpt it [a helmet] for you, surely by definition that would have to be a work of art. The drawings done and things that come out of that are all art," he said.

For Mr Ainsworth, the push to the final episode in his story has a satisfying irony as he says he has only been able to fund the case through his Stormtrooper sales.

"The way we've funded it [the case] is to make the characters, which is the ironic thing about it, it's really the empire striking back," he explains.

"During the period of the court case I've made about 2,000 and sold them around the world."

With his opposing legal army now destroyed like a fading death star, expect to see healthy sales targets projected years into the future.

- Published27 July 2011