Remembering the secret mission of Cockleshell Heroes

- Published

The Royal Marines canoed by night during the secret World War II mission Operation Frankton

A memorial to the Royal Marines who canoed almost 100 miles behind enemy lines to blow up ships in a daring World War II raid has been unveiled in France. But what did the secret mission entail, and why was it so important?

For 10 marines in December 1942, their secret mission was so daring and dramatic they were hailed as the Cockleshell Heroes and in 1955, immortalised in film.

Unbeknown to them when they signed up for "hazardous service", their job was to the attack enemy German ships moored at the port of Bordeaux in occupied France from their canoes.

Only two men survived to tell the tale, but its significance reportedly led Winston Churchill to say he believed the raid could have shortened the war by six months.

"It was one of the worst years in World War II, Great Britain's fortunes were at a low ebb," said Royal Marines historian Maj Mark Bentinck.

"One thing that Britain realised was happening though, was the Germans had a fleet of about 25 ships that were shipping essential materials - such as oils and natural rubber - that they needed for the war effort, back from the Far East.

"They were also shipping hi-tech things like fuses for shells, ball bearings from Europe to the Far East.

"We realised if we could intercept and sink the ships that would greatly help us and damage them," he said.

UK forces could have bombed the ships, but that would have led to a significant amount of collateral damage to the city of Bordeaux. Catching the vessels at sea would have been difficult, so the best place to target them had been in port, Maj Bentinck said.

Norman Colley says the 'Cockleshell' raid was a "suicide mission"

Maj Bentinck said it was a Royal Marine, Maj Herbert "Blondie" Hasler, who came up with the idea of using canoes to paddle up the river and plant limpet mines on the ships.

After about four months of training around Portsmouth, the plan - named Operation Frankton - came to fruition.

At the end of November 1942, 12 Royal Marines set off from Portsmouth on Royal Navy submarine HMS Tuna.

Norman Colley, now aged 90, was one of the marines on board, but did not end up going on the mission because of an injury.

He said it was not until they were on the submarine that they were told what it entailed.

"We knew it was supposed to be dangerous... but we were all about 20 years of age so things like that didn't bother us," he said.

Everyone was "surprised and shocked" when the nature of the mission was revealed, but nobody backed out.

"I thought the lads accepted it very well. Nobody expected to get back off it - it was a suicide mission."

But he said he felt "guilty" a colleague had gone in his place.

"It is a very queer feeling when you see them going away and you know there's not much hope," he said.

"It was a costly operation - you can replace the supplies, but you can't replace the men," he added.

On 7 December, 10 marines were launched near the mouth of Gironde river in five two-man canoes.

Trouble struck when they reached the rapids at the mouth of the river and two canoes were lost. Two men drowned and the other two were captured and executed.

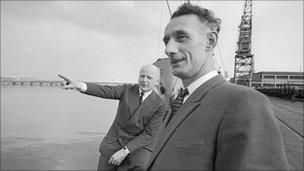

Maj Herbert "Blondie" Hasler and Cpl Bill Sparks (right) were the only two survivors

Shortly afterwards, another canoe was wrecked at sea. The men made it to shore but were also later captured and killed.

Only two crews made it almost the 100 miles to the port - canoeing solely by night and resting by day - to plant mines on the enemy ships. Five were badly damaged in the raid.

The four marines returned down the river, destroyed their canoes and made their way 100 miles on foot through German-occupied France to rendezvous with the French Resistance in Ruffec.

Two men - Maj Hasler and Cpl Bill Sparks - made it, but Marine Bill Mills and Cpl Albert Laver, who won posthumous Mentions in Despatches for their part in the mission, were caught by the French police who handed them over to the Germans. They were later executed.

'Inspirational'

Maj Bentinck said, despite the loss of life, the project was seen as a success.

"First of all it was a great morale raiser, in a war not going our way. Secondly, it was a great irritation to the Germans, who would have had an enormous manpower bill in terms of defending other ships."

He said those involved in the raid were regarded as "inspirational".

"It was a risky operation. And in terms of endurance, the water was freezing, it was winter, there was little room in the canoes, and every night they had to drag them half a mile through mud to catch the tide. These were hardy people," he said.

But he said the British memorial unveiled in the Pointe de Grave - on the headland at the mouth of the River Gironde close to where the marines were delivered by submarine - was as much for the people of Aquitaine, France, as a dedication to the Cockleshell Heroes.

Retired marine Maj Malcolm Cavan, who came up with the idea of the memorial, said he wanted to recognise the part played by French civilians, who had also risked their lives to help and shelter the marines during the raid.

"I became conscious of the huge amount the French had done to reawaken the French consciousness to Cockleshell. They had quietly erected plaques in relevant places - where marines were captured, compromised and executed. What stood out in my mind was the absence of any British memorial in France.

"I thought it was right to focus on the French courage and sacrifice - we wanted a memorial that recognised the French as well as the Royal Navy.

"These were ordinary young people caught up in World War II, who rose to the challenge. There was a huge amount of audacity and courage.

"They were prepared to take it on, and some of them paid for it with their lives," he said.

- Published31 March 2011