British Mau Mau abuse papers revealed

- Published

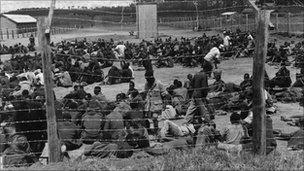

Rounded up: Mau Mau suspects in camps

The first series of documents have been released by the High Court in the legal challenge by Kenyans for abuses and torture more than 50 years ago.

The documents give further details of what ministers in London knew about how the colony was attempting to crush the rebellion that paved the way to independence.

The papers - the first of more than 17,000 pages - contain reports of British officers implicated in atrocities including the murder of suspected Mau Mau rebels.

One document sent to a cabinet minister , externalsays an officer was involved in burning alive a suspect held at a detention and interrogation camp.

Others detail the shock of a senior police commander sent from London to investigate.

Many of the documents released by the High Court on Monday evening were only recently found at the Foreign Office's own archives after years of investigations by academics.

The papers were brought to the UK when Kenya became independent - but unlike other papers, they were never made public in the National Archives. Until weeks ago, they were in boxes at the Hanslope Park archives near Milton Keynes.

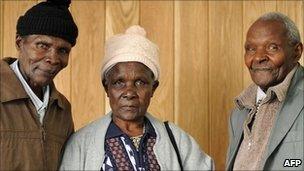

The four Kenyans who are suing the UK say the documents form a paper trail proving that London knew about and approved torture and abuse in Kenya.

The government denies the claim, saying London cannot be held responsible for the actions of a former colonial administration.

The documents, many of which have yet to be reviewed, cover the eight years of the May Mau uprising and emergency and the response in Kenya and London.

State of emergency

L-R: Ndiku Mutua, Jane Muthoni Mara and Wambugu wa Nyingi, three of the Kenyans suing the UK

In 1952, Sir Evelyn Baring, Kenya's governor, declared a state of emergency amid the growth of the Mau Mau movement. It was dedicated to overthrowing the colonial regime.

London sent troops to crush the rebellion, and the Kenyan administration built a series of "screening" or interrogation camps which were designed to break the will of suspects.

Some 150,000 Kenyans were subjected to screening. During the fighting, at least 11,000 rebels were killed - although academics think the true death toll could be more than twice that.

Many suspects taken into the "Pipeline" camps were treated increasingly harshly until they recanted. Others were put on trial in special courts and more than 1,000 were sent to the gallows.

According to the documents, officials were telling ministers as early as 1953 about forced labour in the camps and that "if therefore we are going to sin, we must sin quietly".

But not all officials supported the policies.

Colonel Arthur Young, sent by London to run Kenya's police, complained to Governor Baring about the "inhumanity" , externalof various parts of the security forces amid his investigations of wrongdoing.

"The other lamentable aspect of this case is the horror of some of the so-called screening camps which, in my judgement, now present a state of affairs so deplorable that they should be investigated without delay," said Col Young.

"An African who is unfortunate enough to suffer from the brutalities which are clearly evident has no-one to whom he can complain," he wrote.

"I do not consider that in the present circumstances government have taken all the necessary steps to ensure that in its screening camps the elementary principles of justice and humanity are observed."

He later quit over what he saw - but the documents show that reports were reaching the highest levels of Whitehall.

Telegram to London

In January 1955, Baring sent a telegram to Alan Lennox-Boyd, the Secretary of State for the Colonies and a cabinet minister.

State of emergency: Documents only recently uncovered

Baring told the cabinet minister in the telegram, external that eight European [meaning white] officers had been accused of serious crimes, including accessory to murder. They would be given immunity from prosecution.

One district officer was accused of the "beating up and roasting alive of one African".

A Kenyan Regiment Sergeant and a field intelligence assistance had been implicated in the burning of two further suspects "during screening operations".

"I had not myself realised until today that the extension of the principle of clemency to all members of the security forces involved so many cases with Europeans as principals," wrote Baring.

Dilution technique

The military element of the uprising was effectively crushed in 1956 - but the Kenyan administration still had to deal with thousands held in camps.

Baring's administration devised the "dilution technique" - a system of assaults and psychological shocks to detainees, to force the compliance of the toughest Mau Mau supporters.

Baring telegrammed the Colonial Secretary in London asking for his approval to use "overpowering" force.

Lennox-Boyd was told that one commander, Terrence Gavaghan, had developed the techniques at the Mwea camps in central Kenya - and he needed permission to treat the worst detainees in a "rough way".

The cabinet minister's approval came within weeks, according to court documents.

The papers show that a ministerial delegation saw firsthand prisoners beaten for refusing to don camp clothes. Ringleaders of the "Mau Mau moan" - a chant of defiance - were singled out for special punishment.

They were beaten and forced to the ground. Once there, a boot was placed on their throat while mud was forced into their mouths.

"European officers themselves carried out the violence necessary, the senior ones leading and directing," said the document.

One Hanslope Park document is a letter between Kenyan Special Branch police officers about treatment of "fanatical" detainees at the Mwea camps.

"If they deny having taken an oath they are given summary punishment which usually consists of a good beating up," says the report. "This treatment usually breaks a large proportion.

"If this treatment does not bear fruit the detainee is taken to the far end of the camp where buckets of stone are waiting. These buckets are placed on the detainee's head and he is made to run around in circles until he agrees to confess the oath."

Another minister said that Gavaghan had explained how difficult detainees would be subjected to the "third degree".

"The measures adopted were to be kept awake all night, having water thrown at him and to be beaten up on a variety of pretexts," he wrote.

By 1959, parliamentarians in London were demanding an investigation after 11 detainees were beaten to death for refusing to work.

Alan Lennox-Boyd asked Governor Baring for details of the so-called "Hola incident". , externalHe said he would face questions over the "Cowan Plan", the regime of forced labour under threat of beatings.

"Main criticism we shall have to meet is that 'Cowan plan' which was approved by Government contained instructions which in effect authorised unlawful use of violence against detainees," he wrote.

A later telegram from Lennox-Boyd underlined that London would stand by the governor, external.

"There will be full defence of rehabilitation policy and use of legal force as necessary," he said.

- Published7 April 2011

- Published7 April 2011

- Published6 April 2011