Hidden costs to crime victims

- Published

Victims of violent crime can find themselves tens of thousands of pounds out-of-pocket, according to research completed for the first commissioner for victims and witnesses for England and Wales.

Louise Casey has said victims and witnesses are the "poor relation" of the criminal justice system

Louise Casey has spent her first year in post listening to the views of people who have experienced serious violent crime - as victims, witnesses or families bereaved through murder and manslaughter.

There have been improvements in the last decade and more to the way victims and witnesses are treated. There is a criminal justice system Code of Practice which sets out rules for dealing with the victims of crime.

The code states - among other things - that police forces must appoint a family liaison officer in the aftermath of a killing.

Families can now provide impact statements to the courts so that judges can take them into account when sentencing.

The UK offers the most generous criminal injuries compensation in Europe - paid on a sliding scale, usually up to £11,000 - and, in addition, it has Victim Support, the largest charity of its kind in the world.

Only two months into the job, Louise Casey described the Victims' Code of Practice as "a maybe code which confers no real rights" which crucially, in her view, offers no effective route for complaint.

We have followed the victims' commissioner in her first year for a Radio 4 documentary and listened as families have described feeling completely sidelined in court cases.

Others told how police family liaison officers were not allowed to accompany them to court.

'No money'

Criminal injuries compensation in many cases falls far, far short of what families have to spend.

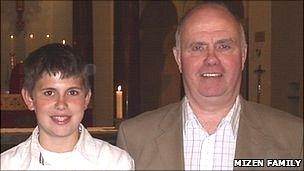

Barry Mizen with his son Jimmy

For example, Barry Mizen, whose son Jimmy was attacked and killed in a baker's shop in London in 2008, is a shopkeeper.

"I'm self-employed and the shop shut," he says. "So there is no money coming in - zero. The last thing we wanted to do at that time was worry about money.

"Fortunately I had one of those mortgages where you get a cheque book, so I wrote one out for £10,000 and I said, 'that will keep us going.'

"To put a definitive figure on it even now, I couldn't, even now, there's ongoing costs, supporting other members of the family."

Louise Casey says she was struck by the fact that, from the moment a murder happens, people - often already without a great deal of money - end up with a great deal less.

She organised research to try to find out how much families spend in the aftermath of a killing, distributing detailed questionnaires through the victims of crime who have set up support and campaign groups to try to help others.

Thirty-six were completed. On average, costs run into tens of thousands of pounds, and more than £100,000 when loss of earnings is included.

Legal battle

Some families also face heavy legal bills when they adopt children left behind.

David Hines set up the National Victims' Association when his daughter Marie was murdered by her former partner Anthony Nicholas Davison 19 years ago, leaving a son Lee, who turned two the day after his mother died.

David Hines and his wife Kathleen were determined to adopt Lee, and he is now their son, but they spent £16,500 in the process.

The killer, who opposed the adoption and wanted access, was given legal aid to take his claim right up to the Supreme Court.

"It put us under tremendous pressure to fight through the family courts," David Hines recalls bitterly.

"We didn't want him to have access to Lee, directly, indirectly or through any third party. We couldn't have the person who'd killed his mother interfering in his upbringing.

"My family through generations have never had trouble with the law. We couldn't understand why the criminal justice system was backing a murderer and not a decent family."

Louise Casey says she has no desire to strip prisoners of their rights but she insists that any help provided by the state in such cases should be fair.

"Either give legal aid to both parties at these hearings," she says, "or don't give it to either."

'Let down'

And where current crime reporting tends to dwell on the emotional impact, what is striking sitting on the edges of these meetings between the victims of serious violent crime and the commissioner, is that the overriding mood is one of anger.

What people often say they want is information on why it was that, in their view, the criminal justice system let them down.

Louise Casey has met people attacked by those released from jail on licence or freed from prison on remand for other serious offences while they were awaiting trial.

"Sometimes there are case reviews," she says, "but the victims of crime are not included in those discussions, not dignified with any kind of explanation."

Louise Casey is expected to deliver her report to the Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke in June this year.

Giving Voice To The Victims will be broadcast on Tuesday 10 May at 2000 BST on BBC Radio 4. It will also be available on the BBC iPlayer.