Britain's mysterious baby boom

- Published

- comments

Women in the UK are having more babies

Britain has undergone a dramatic baby-boom in the first part of this century - and experts suspect that, inadvertently, Tony Blair is the daddy.

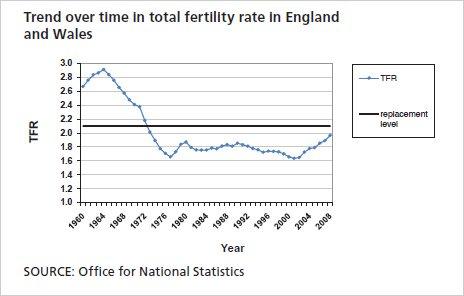

According to a report out today, women in the UK have suddenly started to have significantly larger families: in 2001 the average was 1.64 but by 2008 it was 1.97.

Quite why the noughties should have inspired such a turnaround in Britain's fertility rate is something of a mystery. The experts are confident the explanation is not immigration but think it might be an unintended consequence of policies to reduce child poverty.

You may remember all those Doomsday scenarios a decade ago of imploding European populations, with fertility spiralling downwards. Well, it hasn't happened. Fertility rates across the EU have stabilised and increased in some countries - notably the UK.

While the chances of reaching the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman looked "remote" for Britain in the early years of the millennium, it "now appears much more likely".

Something extraordinary occurred shortly after Tony Blair became prime minister that, according to research by the think-tank Rand Europe, external, meant "of all the countries of the European Union, the UK has had one of most dramatic turnarounds in period total fertility over the last five years, with recent gains more than reversing the slow decline of the previous two decades".

The graph tells the story: the high fertility rates (TFR) of the sixties plummeted with the availability of the contraceptive pill and stuck well below the level required to replace the population for 25 years.

It was a similar story in many developed European countries and the warnings inspired some governments to introduce policies encouraging their citizens to breed. The European Union, fearful of an economic catastrophe from low fertility rates and an aging population, made a clear commitment in 2005 to "demographic renewal".

The British, however, have traditionally rejected the notion of politicians interfering in family life. As today's Rand report puts it: "Successive UK governments have pursued an essentially neo-liberal policy, leaving decisions about childbearing to families and maintaining a laissez-faire attitude towards the economy."

So, British changes to the fertility rate are accident rather than design, which makes the steep rise during the last decade all the more curious. Whatever happened here was sufficiently dramatic to outstrip the concerted efforts of other countries to achieve the same result.

It is all a bit of a puzzle. The experts at Rand Europe looked at a range of explanations as to why British women had, apparently, changed their minds about having larger families.

Like many people I suspect, my immediate thought was that higher fertility rates might be a consequence of higher immigrations levels. Apparently not.

Immigration has had an impact on the birth rate (the number of babies): foreign mothers now account for a quarter of all births.

Immigration has not had any significant impact on the fertility rate (babies per mother): the big increase in immigration between 2001 and 2008 was from Eastern Europe, notably Poland, but women from the accession countries do not generally have more babies than British-born mothers. In fact, the fertility rate in Poland is significantly lower than the UK - 1.2 in 2003 and now just under 1.4.

"Overall, the total effect of immigration over the past 50 years has probably been to slow the decline in TFRs due to the higher fertility (on average) of foreign-born women, particularly those from the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan and Bangladesh). However, the immigration of people from Eastern Europe since 2004 is unlikely to have had any impact on the increase in TFRs since 2001."

If anything, greater restrictions on immigration from higher fertility non-EU countries following the wave of arrivals from lower-fertility Poland probably had a negative effect on fertility. The mystery deepens.

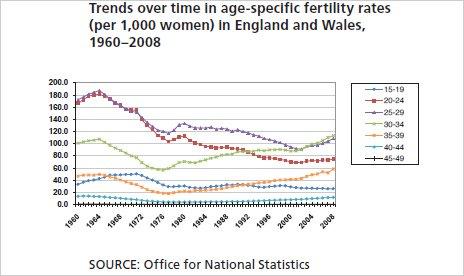

We know that throughout the 1980s and 90s women in the twenties were having fewer babies than previously while women in their late thirties saw a moderate rise in fertility rates. In 2001 something changed.

The story of this graph is the purple line - women aged between 25 and 29. Fertility rates had been falling inexorably since 1980 and then in 2001 the trend reverses. It is almost as if women in their late twenties realised the thirty-somethings were overtaking them in the baby-stakes and decided to get breeding.

What really inspired that change? The Rand Europe researchers rule out a number of possible factors: GDP seems unrelated to fertility rates; higher levels of female education and labour force participation don't appear to have any impact; fewer and later marriages have probably had a negative effect on fertility because married couples tend to have more babies (although divorce and remarriage might mitigate this effect). It was something else.

In the end, the researchers concluded the most likely explanation was a policy never intended to fill the maternity wards - New Labour's commitment to eradicate child poverty.

At first, the evidence didn't look too convincing: the impact of welfare changes appeared to be "ambiguous". The reforms were thought to cut both ways because "families with greater income may be able to afford to provide for more children, but better job prospects and earning power increase the amount of income forgone when parents take time out of the labour market to raise children."

One aspect of the reforms, though, did seem to have a significant impact on people's decision to have more children - working family tax credits (WTFC). One study found that the payments increased the fertility of women in couples by 10%. Why? The money was expected to encourage mums back to work. Instead, they were staying at home and having another baby.

"This difference may be explained by the fact that eligibility for the WTFC depended on one of the couple working: many women in couples found that the WTFC increased family income without providing any incentive to enter the labour force, and may even have enabled them to drop out of the labour force in response to their partner's increased earnings."

As the researchers put it, "in attempting to improve the quality of children's lives, the policies are likely to have had the unintended effect of increasing the quantity of children born".

It is a reminder, perhaps, of how the law of unintended consequences works. Tony Blair's determination to help the young may have, inadvertently, helped with the challenge of the old.