Scrap pension age, academic says

- Published

Professor Harper said pensions should be based on the number of years someone has worked

A researcher into ageing is calling for the government to scrap the pension age and instead base entitlement on the number of years someone has worked.

The Commons is due to debate the Pensions Bill, which would see the entitlement age for women rise from 60 to 65 by 2018, and then increase to 66 for both sexes by 2020 to cover increasing costs as more Britons live longer.

Oxford professor of gerontology Sarah Harper is one of the authors of a report into the impact of increased life expectancy on pensions entitled Living longer and Prospering?, external.

She said life expectancy was increasing by about three years a decade, and it was clear the pensions system needed to be adjusted.

"The state pension age does tend to influence when people retire," she said.

"It's ridiculous retiring in our 50s when we're living to 100."

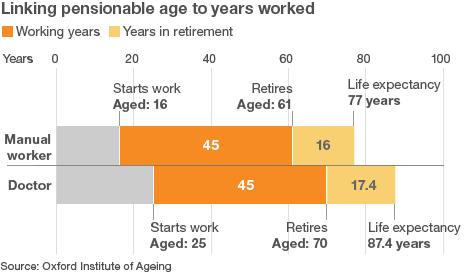

But she said raising the pension age would not reflect the discrepancies in individuals' life expectancy, and it would be fairer to move the pensions system away from age and instead relate it to the number of years worked.

"The idea that we clump everyone together and say everyone at 65 is the same has no evidence at all," she said.

'11-year difference'

Researchers found that a low-income male, with an unhealthy lifestyle who retired at 65 in ill health, could expect to live another 12 years.

Retiring in good health would lengthen his life by a further 1.8 years. If he also had a healthy lifestyle he could live an additional 4.6 years, while earning a high income would add another four years, and being in a non-manual job would add 0.7 years.

"If you're a man in this country, you're unhealthy, you're on a low income, you're a manual worker, when you retire at 65 your life expectancy is probably only around 75-77," Professor Harper said.

"If, however, you're healthy, you're on a high income, you're maybe managerial and professional, you could easily reach your late 80s - indeed there's an 11-year difference."

She said if everyone had to work for 45 years before receiving a pension, a manual labourer with a lower life expectancy who had started work at 16 would probably still have 15 years of retirement, as would a professional who had entered the workforce later after further education.

"If you look at the life expectancy of those who stay in education until their mid-20s they can probably afford to work another five years," she said.

If the government continued to raise the pension age, she said, an increasing number of people could end up being too ill to work before they could access it.

"We've got to take into account the great differential and make sure we don't have a group who are going on to state disability allowances before they go on to state pensions."

But if state pensions were to be based on number of years worked, provision would have to be made for some groups of people who had been outside the workforce, Professor Harper said.

She pointed to people who had been caring for dependents - such as women looking after children - the registered unemployed and those who had left the workforce to increase their skills through lifelong learning and education.

"We don't want this idea to deter people who leave work for the good of society, the economy and themselves," she said.

Researchers had access to the records dating back to the 1970s of 1.8 million occupational pension records held by Club Vita.

- Published20 June 2011

- Published18 June 2011

- Published8 June 2011

- Published20 October 2010