Gilbert and Sullivan's mystery play

- Published

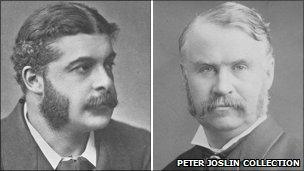

Laughter has an echo that is grim: Philip Cox and Richard Gauntlett as Shadbolt and Jack Point at the Buxton festival

It is 100 years since WS Gilbert died, aged 74, 10 years after Arthur Sullivan. From the 1870s to the 1890s each of their comic operas in turn had captivated a huge public across the English-speaking world.

Ever since, they have been a sure way to fill venues from opera house to tin shed. This year's Gilbert & Sullivan Festival in Buxton is the biggest ever, with some 50 productions., external But who was the driving force in the partnership?

Was it Gilbert, the writer of sparkling lyrics with a sting in the tail? Or Sullivan, the master orchestrator and creator of unforgettable tunes?

Part of the answer lies in their oddest opera, the one where they went "serious" - the Yeomen of the Guard of 1888.

'Falls insensible'

Amid the fine Derbyshire scenery, festival-goers are united in their love of the immortal pair.

But a quick survey at the enthusiasts' memorabilia fair found many disagreements on one point: does the jester die at the end of the Yeomen of the Guard?

This year's Gilbert and Sullivan festival at Buxton is the biggest yet

Now, these are people who know their G&S. They know that the stage direction says only that Jack Point "falls insensible" at the end. And they know that other Gilbert & Sullivan characters "fall insensible" and stage a happy recovery.

But a good many of those asked support the general view: Jack Point definitely dies.

A few are sure he does NOT die. Many are uncertain. "It's a very tragic ending but I'm not sure he's actually dead," says one woman. "Perhaps he falls over from sheer stress".

"It's comic opera," says another. "Gilbert doesn't mean him to die - just to make a really dramatic ending."

"I think he crawls away to die quite soon afterwards," says a man at the fair. Others reflect the uncertainty: "That's what we'd all like to know.... Deliberately ambiguous... Gilbert deliberately left it open... It's up to the viewer".

The Yeomen emerged from a crisis in the partnership. The pair's last work, Ruddigore, had had a mixed reception. Someone in the audience shouted: "Take it away and bring back the Mikado."

Sullivan was impatient with Gilbert's "topsy-turvy" stories where characters constantly turn out to be someone else and plots hinge on legal quibbles.

He was also very ill, taking morphine for a serious kidney complaint. He wanted more attention for his music, not Gilbert's words. And he wanted to write a grand opera.

Gilbert (right) urged Sullivan not to change their old working partnership

Richard D'Oyly Carte, who had built the Savoy Theatre for Gilbert and Sullivan's works and prospered along with them, also wanted to move on with a new theatre and a new company.

Gilbert pleaded with Sullivan not to break up the old arrangement, saying: "We are as world-known, and as much an institution as Westminster Abbey."

But he had to make concessions. "Sullivan's pressure won the day, and Gilbert wrote the kind of libretto Sullivan had wanted all along," says David Eden, editor of the Cambridge Gilbert & Sullivan companion.

Sullivan kept the normally domineering Gilbert hard at it. It shook Gilbert when Sullivan required a large part of the second act to be rewritten at short notice.

'Not much comedy'

In the story Jack Point loses his love, Elsie, to Colonel Fairfax, who is condemned to death in the Tower of London, escapes disguised as a Yeoman of the Guard, and is then acquitted.

It is "a comic baritone role without much comedy", says Richard Gauntlett, playing Jack in the festival at Buxton.

Sullivan liked it and said it contained "no topsy-turvydom".

Well... It has a plot based on a legal mix-up and mistaken identities; a crop of weddings and engagements to tie it up at the end; patter songs; song-and-dance encores, and plenty of jokes.

In fact if Jack Point were not in it, or did not love Elsie, it could be a light-hearted opera like all the others.

But it can be played as a very dark piece. It contains the only scene of real violence in Gilbert and Sullivan, when a jeering mob molest Point and Elsie.

One of the main characters, Shadbolt, is a torturer, and discusses his art in all-too-believable terms.

And there is the mystery - does Jack die at the end?

"Oh yes, he dies. He must die," says Richard Gauntlett. "I'm in the old school about that."

In the first production Jack was played by George Grossmith, the most popular comic actor of the day. He did not think the public wanted to see him die on stage, and "used to waggle his foot" to reassure them, says Gauntlett.

And Gilbert wrote a happy ending too. In the first rendering of the best-known number, I Have a Song to Sing, O! the merry maid is spurned by the lord she loves and returns to her jester.

But when the song is repeated at the end she sheds a tear for the jester, then rejects him.

Now there is an argument - "persuasive", G & S scholar Ian Bradley calls it - that Jack Point represents Gilbert himself. And if so, it is tempting to see Gilbert's woes mirrored in Jack's.

Certainly there are many lines like this suggesting it:

"When a jester is outwitted, feelings fester, heart is lead.

Food for fishes only fitted. Jester wishes he was dead..."

Dead or not, who won in the contest between him and Sullivan over writing more serious work?

Sullivan wrote his grand opera, Ivanhoe, which D'Oyly Carte put on at his new theatre in 1891. The libretto was written by Julian Sturgis, who had played in the 1873 FA Cup Final.

It was a success at the time, but the new theatre was not, and there were no more grand operas from Sullivan.

Gilbert and topsy-turvydom won, too. He and Sullivan wrote The Gondoliers, put on at the Savoy in 1889, with nothing serious in sight.

- Published3 August 2011