Phone hacking: Should reporters break the law?

- Published

- comments

Is media transparency the answer?

There is a neat irony in my long-time colleague Paul Lambert - aka "Gobby" - having his parliamentary pass withdrawn and swiftly returned after breaking Palace of Westminster rules.

The episode is a metaphor for the bigger question that bubbles away behind the phone-hacking scandal: is it ever legitimate for journalists to break the law in pursuit of a story?

Paul's professional instinct was to film the aftermath of the foam attack on Rupert Murdoch, an incident that was clearly highly newsworthy and which posed questions about security arrangements inside Parliament.

He knew, though, that his access to the palace was sanctioned on the basis of a set of rules including tight restrictions on filming. Was he right to turn on his camera even though it was against the regulations?

In arguing that Paul have his pass returned, the Tory MP Louise Mensch told the Commons yesterday:

"I hope that the House will agree with me that it's appropriate that we support freedom of the press, particularly when the press are reporting on serious failures of security in this House."

There was a similar response on Twitter, where a campaign quickly developed to #saveGobby, external, demanding he have his parliamentary privileges restored.

Paul was not, of course, breaking the law of the land, (although it wouldn't surprise me to learn that the Sergeant at Arms possesses the power to string up palace rule-breakers in that cell beneath Big Ben).

'Deception and subterfuge'

However, the question of principle is similar. Can it ever be legitimate for journalists to behave illegally?

The Leveson inquiry, we now know, will "look not just at the press, but at other media organisations, including broadcasters and social media (to see) if there is any evidence that they have been involved in criminal activities."

They will undoubtedly find some. The next question is whether that is always a bad thing.

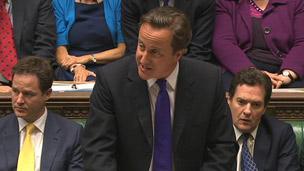

Most reporters would argue that, yes, there are occasions when the public interest is so overwhelming that law-breaking can be justified. The prime minister said as much during the Commons debate yesterday, external.

"None of this is easy, and a point that must not be lost in this debate is that to over-regulate the media could have profoundly detrimental effects on our country and our society. We must not miss this in the frenzy about the dreadfulness of hacking at this point. Without a public interest defence, the so-called "cod fax" that uncovered Jonathan Aitken's wrongdoing might never have emerged. To give another example, are we seriously going to argue in this House that the expenses scandal should not have come to light because it could have involved some data that were obtained illegally?"

However, it is arguable that the phone hacking scandal is a consequence of journalists believing that tacit permission occasionally to operate outside the law inevitably means some will assume they are "above the law".

I have looked at newspaper and broadcasting codes on investigation and the public interest. None are explicit about the need for journalists to obey the laws of the land. Indeed, there are hints that it is sometimes OK to use illegal methods to get a story.

The Press Complaints Commission code, external, for instance, says this: "Engaging in misrepresentation or subterfuge, including by agents or intermediaries, can generally be justified only in the public interest."

David Cameron recalled Parliament to make a statement on hacking

The Ofcom code, external for broadcasters says something similar: "It may be warranted to use material obtained through misrepresentation or deception without consent if it is in the public interest and cannot reasonably be obtained by other means".

The NUJ code states, external that journalists must obtain material by "honest, straightforward and open means, with the exception of investigations that are both overwhelmingly in the public interest and which involve evidence that cannot be obtained by straightforward means."

This suggests, therefore, that there are some occasions when it is legitimate to obtain material in ways that are not "honest".

The question which follows, of course, is what we mean by "public interest". The PCC code says "the public interest includes, but is not confined to:

Detecting or exposing crime or serious impropriety.

Protecting public health and safety.

Preventing the public from being misled by an action or statement of an individual or organisation."

The BBC's own code offers another definition of public interest. There is no single definition of public interest. It includes but is not confined to:

exposing or detecting crime

exposing significantly anti-social behaviour

exposing corruption or injustice

disclosing significant incompetence or negligence

protecting people's health and safety

preventing people from being misled by some statement or action of an individual or organisation

disclosing information that assists people to better comprehend or make decisions on matters of public importance.

There is also a public interest in freedom of expression itself.

Both definitions are open-ended, the list of examples prefaced by the phrase "not confined to". As a journalist, I would agree that it is dangerous to describe the public interest too specifically because it would almost inevitably lead to clever lawyers ensuring dodgy clients keep dark secrets.

'Public defence'

That is why, I think, the Leveson inquiry will not want to rely on a tightly defined "public interest" in deciding when a free press can stray into legal grey areas. An alternative approach could be based upon a concept much in vogue within government - transparency.

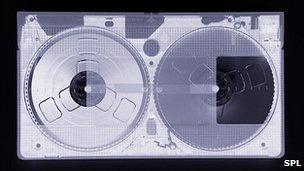

Could phone hacking ever be justified?

I have used secret filming in stories. On one occasion, I was personally wired up with a hidden camera and microphone. I don't think I ever broke the law in what I did, but there were certainly ethical and professional questions to be considered and a detailed internal process of compliance.

Having obtained the evidence in what we regarded as the "public interest", we then broadcast it in a way that made it clear to the viewer exactly how the material had been gathered. Secret filming was clearly and deliberately branded as such.

This principle of being up-front as to how a story is obtained offers some potential clarity in the murky environment of journalistic subterfuge and law-breaking, it seems to me.

If the media were generally obliged to be open about their methods, then the debate about how far the "public interest defence" should apply could be conducted on a story by story basis.

The problem we have is that the public (until very recently at least) seemed relatively untroubled about reporters using dubious and, on occasion, illegal methods to reveal salacious details of the private lives of celebrities.

They are, however, understandably appalled at such tactics being used to get information about murder victims, soldiers lost in action or grieving families.

No journalist would ever want to do anything that might reveal a confidential source or jeopardise the innocent. But that is not what is really at stake here.

The argument is one about justifying behaviour on the basis of principle rather than the law. If we can argue our case, then perhaps that is what we should be obliged to do.