A history of social housing

- Published

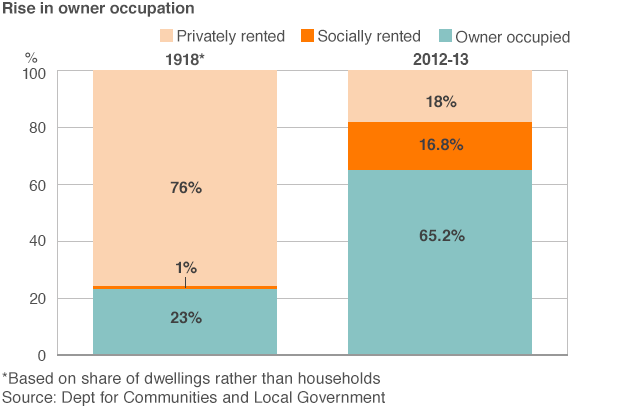

From Lloyd George's promise of "homes fit for heroes" to Margaret Thatcher's dream of a property-owning democracy, housing has been at the centre of British politics for more than a century. Key pledges ahead of the 2015 general election show it's rarely mattered more. Here is why.

Labour voters lived in council houses. Tories owned their own homes.

That's the way it had always been.

Yet for a young Labour MP, out canvassing in his constituency in the early 1980s, it still came as a shock to be told, by an old party stalwart, that there was no point knocking on doors on a private housing estate, as they all voted Tory.

To Tony Blair, it was a sign of just how out of touch his party had become with ordinary working people.

Tony Blair understood the power of home ownership

Millions of people owned their own homes (or aspired to). Did Labour have nothing to say to them?

Blair's supporters in his North-East of England constituency, battling crippling levels of unemployment in a former mining area, needed the guarantee of a decent home for their families at a reasonable rent that council housing provided.

But, Blair reasoned in articles at the time, Labour would never again be in a position to help them as a party of government unless it learned to connect with owner-occupiers, particularly in the South of England.

Blair's epiphany came at the height of Margaret Thatcher's "right-to-buy" revolution.

Giving council tenants the opportunity to buy the homes they were living in - at a generous discount - was one of the defining policies of the Thatcher era.

More than two million council tenants - many of them traditional Labour voters - took advantage of it.

At the time, it seemed like the fulfilment of a longstanding Conservative dream, first spoken about in the 1930s, of creating a "property-owning democracy".

Ordinary working families now had assets that they could pass on to their children, Tory MPs boasted, and the opportunity to escape the modest circumstances they were born into.

The policy had been pioneered by Lady Thatcher's predecessor as Tory leader, Ted Heath, in the early 1970s, although local councils have had the right to sell off their council housing stock, with ministerial approval, since 1936.

Housing became an obligation for councils, under Lloyd George

Local authorities had been required by law to provide council housing since 1919 and Lloyd George's "Homes fit for Heroes" campaign sparked by concerns over the poor physical condition of army recruits.

But it was not until after World War II that the age of the council house truly arrived.

Clement Attlee's post-war Labour government built more than a million homes, 80% of which were council houses, largely to replace those destroyed by Hitler.

The house-building boom continued when the Conservatives returned to power in 1951, but the emphasis shifted at the end of the decade towards slum clearance, as millions were uprooted from cramped, rundown inner-city terraces and re-housed in purpose-built new towns or high-rise blocks.

A generation was introduced to the joys of indoor toilets, front and rear gardens, and landscaped housing estates where, as the town planners boasted, a tree could be seen from every window.

But the post-war dream of urban renewal quickly turned sour.

By the early 1970s, the concrete walkways and "streets in the sky" that had once seemed so pristine and futuristic, were becoming grim havens of decay and lawlessness.

And there was a powerful smell of corruption emanating from some town halls as the cosy relationship between local politicians and their friends in building and architecture was laid bare, along with the shoddy standard of many of the "system-built" homes they had created.

It was against this backdrop that "right to buy" began to take off, with the number of council houses sold in England going up from 7,000 in 1970 to nearly 46,000 in 1972.

It was not, initially, opposed by Labour.

In 1977, Labour housing minister Peter Shore published a green paper endorsing home ownership as a "strong and natural desire" which "should be met".

He backed shared equity schemes, aimed at getting council tenants on the property ladder, and the growth of the housing association movement, although he still envisaged that the bulk of the nation's affordable housing needs would continue to be met by local authorities.

But the world Shore was describing was about to be swept away by the 1980 Housing Act and the explosion of "right-to-buy".

The Labour Party, which had lurched to the left under Michael Foot, bitterly opposed the "right-to-buy" arguing that it would lead to a dangerous depletion in council housing stock.

They also feared it would spell the end of Labour's vision of a "cradle to grave" welfare state, as working class people embraced a more materialistic, Thatcherite way of life.

By the time Tony Blair came to power, in 1997, such rose-tinted notions were a thing of the past.

New Labour was an enthusiastic champion of the right to buy and home ownership in general, seeing it as its mission not to ensure affordable rents for working people but to help them get a foot on the property ladder.

Mr Blair and his chancellor, Gordon Brown, presided over an unprecedented boom in house prices, fuelled by cheap credit and a shortage of affordable rented accommodation.

The "right-to-buy" phenomenon had led, as some on the left had predicted, to a massive depletion in council housing stock - made worse by the refusal of successive governments to allow local authorities to spend the windfall they received from council house sales on building new ones.

The housing bubble was also fuelled by the "buy-to-let" phenomenon, as speculators bought up rundown former local authority housing as a source of income.

Council housing estates were fast becoming the accommodation of last resort for those left behind by society, as families on middle incomes sold up and moved out.

People living on estates increasingly tended to be on benefits or in low-paid work, or had drug and alcohol problems.

The growth in asylum seekers and economic migrants, towards the end of Labour's time in power, added further to the pressure on the system.

Efforts to build more social housing in the dying days of Gordon Brown's premiership were, most observers agreed, too little and too late.

And the near collapse of the banking system ended the hopes of many on average incomes of ever owning their own homes.

With the amount demanded by banks as a mortgage deposit, a growing number of working people found themselves trapped in costly private rented accommodation until early middle age.

Since 2010, a decade-long decline in council house sales has been reversed thanks to the government's decision to increase the maximum discount available to tenants to £75,000 - £100,000 in London - and reduce the qualifying period to three years of residence in a property.

In the early years of the coalition, it acknowledged the housing crisis to be one of the biggest problems it faced.

Its first housing minister, Conservative Grant Shapps pledged to kick-start building, which had fallen to its lowest level in decades, by releasing more public land and easing planning restrictions.

But by 2012-13, with the country still recovering from the effects of the financial crisis, the total of new homes built hit a post-war low of 135,500. While that figure recovered slightly the following year, construction output again dipped at the end of 2014.

The Home Builders Federation has complained that - despite improvements - the planning system is "still far too slow, bureaucratic and expensive". However, highlighting that the number of planning permissions for new homes had reached 240,000 in the year to September 2014, housing minister Brandon Lewis said the government's planning reforms were working.

That number is still 10,000 fewer than the Barker Review of Housing Supply said was required a decade ago.

As the 2015 election looms, each of the major parties has a pitch to voters on housing. The Conservatives made the extension of the right to buy to housing association properties their major manifesto announcement, saying each house sold would be replaced. They say they'd set up a fund to build 400,000 new homes - with 200,000 for first-time buyers aged under 40, offered at a 20% discount.

Labour is promising to get 200,000 homes built a year by 2020. The Lib Dems say they'll increase housebuilding to 300,000 a year and build 10 new garden cities, while the Greens promise 500,000 social rented homes by 2020 and UKIP says it would establish a brownfield agency to provide housing grants and loans.

But whoever wins power, it seems there is no chance of a return to the days when government ministers proudly cut the ribbon on giant new council estates on the edge of town.

Time and the aspirations of voters - in a country where the national obsession is property prices - have moved on.

- Published13 January 2015

- Published14 April 2015

- Published13 March 2015

- Published4 April 2015

- Published29 July 2011

- Published15 January 2011

- Published13 December 2010