Somalia drought: Tragic history repeats itself

- Published

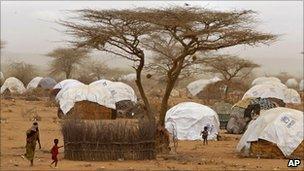

Most residents at the Dadaab camp are long-term residents, who came here fleeing previous disasters

I'm here on the edge of the harsh Ogaden desert, in the north-eastern corner of Kenya, to tell the story of a humanitarian crisis.

The Somalis who make the perilous journey here - mainly women and children - are in dire need. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, will die no matter what the aid agencies do - it is already that bad.

The stick-thin babies - we have all seen the images. The mothers who have arrived here with fewer children than when they set off from their homes - we can only imagine their desperation.

But that is only part of the story. It is the one that is getting most attention but it is the one that is least likely to lead to a lasting solution to what is happening in Somalia.

One stark fact shouts louder than all the others we have been bombarded with since famine was declared in Somalia.

The vast majority of people in this massive camp of 440,000 people (roughly the population of the UK city of Leeds) are not here because of this year's drought. That's right - three out of four people receiving food aid are not starving.

Most of them have been here for more than a decade and a substantial number have been here for two.

They are victims, but they live in this tented encampment in a God-forsaken corner of Africa not because they are hungry, but because the country they once called home is dysfunctional.

In fact, it is a country in name only. It is the failed state of diplomatic nightmares.

Man-made

It all started some 20 years ago when I first criss-crossed Somalia as a relatively new foreign correspondent for the BBC.

We saw similar images of suffering from Somalia in 1992

The fall of a dictator had been followed by internecine conflict as competing warlords defended their territories with a ruthlessness that gave new meaning to scorched-earth warfare.

Then, too, there was a drought, but the famine that ensued was as much man-made as induced by climate.

That is when the first desperate Somalis fled across the border to Dadaab, where I am now, watching a new tragedy unfold.

In the intervening years the violence of the warlords has been replaced by a new civil war between a Western-backed government that is staggeringly inept and a collection of Islamist militias ranging from pragmatic to extremist.

It is the reason why the 300,000 Somalis who were already here have not gone back and why a hugely expensive aid operation is being mounted here in Kenya rather than inside Somalia where it would be much more efficient and effective.

Conflict, not drought, is the reason so many Somalis are dying needlessly.

Conflict has turned hunger into famine and disaster into tragedy. I know it, the aid workers know it and so, too, do the refugees.

As Rukiya Ahmed Gele, a refugee since 1992, told me outside a UN food distribution centre: "Maybe if they stopped feeding us here we would have to go back and sort out our problems."

Hers is a drastic solution. What is clear that charity alone is not enough to solve Somalia's problems.

If these problems are not tackled there is every chance that another reporter will be back in another 20 years wondering how it is possible that vulnerable children are still being cursed with hunger and a horribly early death.