England riots: The return of the underclass

- Published

- comments

Tottenham locals reflect on riots

The Tory party's social policy guru Iain Duncan Smith believes Britain has witnessed the growth of a "more menacing underclass, external".

Listening to the voices on some of England's toughest estates trying to justify the rioting, looting and arson, it would be easy to concur with his theory of a "new generation of disturbed and aggressive young people doomed to repeat and amplify the social breakdown disfiguring their lives and others round them".

It had been thought the word "underclass" with its connotations of fecklessness and criminality had been expunged from the New Labour government's lexicon.

But it is back, a headline-writer's shorthand for the undeserving and dangerous poor who are burning and robbing their own communities.

Within weeks of coming to power in 1997, Tony Blair set up a Social Exclusion Unit inside the Cabinet Office specifically to deal with what his party painted as Margaret Thatcher's underclass - hundreds of thousands of people, workless, skill-less, often homeless and hopeless, a group cut off from mainstream society - dubbed the entrenched 5%.

Huge sums were pumped into schemes in the most deprived neighbourhoods, but tussles over budgets and the sheer challenge of engaging with people who are often hostile to officialdom meant ambition couldn't translate into outcome, external.

Instead Tony Blair went down the Respect Agenda route, pre-empting the rhetoric of responsibility and good manners that is now the language of the coalition.

Reporting as I have done from countless urban sink estates over the years, I have met many teenage lads baffled and resentful at their lack of opportunity to participate in the consumer society they care so much about.

It comes as little surprise that the looters have targeted trainer stores and sports shops.

Right and wrong

The commentator David Goodhart suggested, external this week that "laissez-faire liberalism (of the right economically, and the left culturally) has left too many people adrift, especially in the inner city, without sufficient structure or sense of obligation or meaning in their lives."

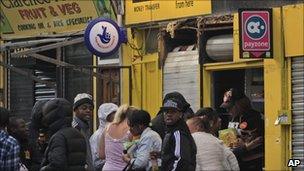

Many of the businesses targeted by looters were owned by people from the same communities

Yesterday, the prime minister suggested he agrees with this analysis when he said the problem was "a complete lack of responsibility, a lack of proper parenting, a lack of proper upbringing, a lack of proper ethics, a lack of proper morals."

That is what we need to change, he said.

But how? The Social Exclusion Task Force (as the Social Exclusion Unit became known after it was merged with the PM's Strategy Unit in 2006) has been wound up, its Whitehall interventionism at odds with Big Society entrepreneurism.

Mr Cameron stresses the importance of "discipline in schools" and a "welfare system that does not reward idleness".

His party's Work Programme is another great hope in getting the long-term jobless into employment. There's no money, he's relying on carrots and sticks supplied by others. Is that going to be enough to reach the entrenched 5%?

The politics

As MPs prepare for today's parliamentary statement on the disturbances, all parties are anxious that they cannot be portrayed as apologists for the rioting, blaming some perceived political failure that plays to a partisan case.

"Let's have the sociological argument in the weeks and months ahead", Nick Clegg said on the Today programme, external this morning.

But the question will have to be asked and answered at some point.

There have to be reasons why thousands of people have attacked their own neighbourhoods when, as the prime minister says, their behaviour is so obviously spectacularly counter-productive.

The Brixton riots, which lasted for three days in 1981, were sparked by the arrest of a black man

Destroying the businesses which bring wealth and jobs, attacking the officers trying to keep people safe, creating a climate of fear and resentment, all are certain to make lives worse not better.

When American inner-city streets were burning in 1967, President Lyndon Johnson set up a commission on civil disorders to answer three basic questions about the riots: "What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?"

The subsequent Kerner Report was dismissed as deeply flawed by conservatives who argued that it exonerated rioters for their criminal behaviour and placed the blame on wider society.

So when Lord Scarman was asked to "inquire urgently into the serious disorder" in Brixton in 1981, he was careful to insert a paragraph which said "the social conditions do not provide an excuse for disorder - all of those who in the course of the disorders in Brixton and elsewhere engaged in violence against the police were guilty of grave criminal offences".

But he did accept that social circumstances had created a "predisposition towards violent protest".

Is there such a predisposition now?

Can the root causes of the violence be pinned on bad politics as opposed to simply bad kids, bad parents and bad morals - "criminality - pure and simple"?

When the Home Affairs Select Committee completes its inquiry it will find itself treading that narrow line between condemning and contextualizing the unrest, but it would be hard to imagine any such investigation not wanting to consider what policies will be most effective in ensuring England's social landscape does not have parts left tinder-dry and combustible.

The bewildering events of the past few days are a reminder of why, however difficult, no country can afford to ignore any strata of its society.