England riots: Would you shop your child to the police?

- Published

Police have praised parents for handing their children in

Your teenage son or daughter comes home with ill-gotten gains from the recent looting and you catch them red-handed. So do you hand your own offspring over to the police?

It's a moral dilemma no parent wants to confront for real.

The idea that your child is involved in events that shocked you and a nation is hard enough, but then you've got to decide what to do about it.

For some, choosing whether to hand your child into the police depends entirely on the severity of the crime. Parents have to weigh up the damage a criminal record might have on their child's future prospects - not to mention the strain on their relationship.

Others are unequivocal. Children have to learn to face the consequences of their actions, regardless of the anguish that might cause.

'Very upsetting'

Speaking through her tears, Adrienne Ives explained why she turned in her 18-year-old daughter Chelsea after seeing pictures of her allegedly rioting on the TV news.

"It's very upsetting. It's a hard decision to make, but it's a decision that any good parent would do," she told reporters outside her home in Leytonstone, east London.

"I just hope that other people find that courage. I just done what I felt was right."

Chelsea Ives, an Olympics ambassador, denies violent disorder, attacking a police car and two counts of burglary.

On Friday, two boys aged 15 and 14 were handed in by their mothers after they were allegedly pictured taking part in riots in Salford, Manchester.

A judge on Saturday praised the parents of the 14-year-old, telling the court: "I only wish more parents took their responsibilities as seriously."

Police in Manchester, who have set up "shop a looter" boards, described the actions of the 15-year-old's mother as "extremely admirable" and thanked her for handing him in.

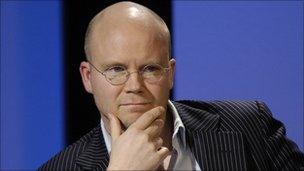

Frogmarching your child to a police station may be overzealous in some circumstances, says Mr Young

While some of the looters and rioters now in custody were shopped by parents who simply suspected their children were involved, many more were turned in once suspects' pictures were posted on mobile screens and advertising vans. In that situation, parents may have felt it was better they acted first rather than wait for the knock on their front door.

For Margaret Morrissey, founder of campaign and support group Parents Out Loud, there is no question that any parent who took such action did the right thing.

"Sometimes love's got to be very tough and tough love does help," said the mother-of-two.

"It's saying... we will support you, but this is what happens if you do something that is morally and criminally wrong to society.

"It means not that I care for you any less, it means probably that I care for you more."

She admitted it would cause "incredible heartache" and distress, but "to preserve society for you and your children, you have to pay the price".

Employment prospects

But writer, campaigner and parent Toby Young, who is setting up one of the UK's first free schools, disagreed.

Asked whether he would turn in his children, he told the BBC: "I think it depends on the severity of the crime. Murder, yes, obviously.

"Looting? If my child was guilty of taking something from a shop that had been broken into, probably not.

Greater Manchester Police say they have been "inundated" with tip-offs after their campaign

"You'd have to weigh up the wrongness of what they'd done against the damage it could do to their future employment prospects.

"If it was the first time they'd broken the law and they got caught up in the heat of the moment and weren't themselves, then it might be overzealous to frogmarch them into a police station."

He said he would nevertheless insist they pay the shopkeeper back in full - "albeit anonymously".

People discussing the issue on online forums appear more in favour than not of handing their children in, but there were warning voices too.

One writes: "I would deal my own punishment. Wouldn't want to mess any future chances for my child by them possibly having a criminal conviction.

"Love the way everyone says 'yes', but in the real world would you really?"

Another points out the perils of having to disclose a criminal record for five years or more.

For some parents whose children are caught up in a long-term cycle of addiction and crime, the decision to call in the police can be more straightforward.

Caroline Goodall, 47, from Bradford, has spent the last 11 years trying to cope with her daughter's heroin addiction, thefts, car break-ins and court appearances.

Her daughter - who is now now 23 and no longer living under her roof - first started using heroin aged 12, and was soon stealing from her, as well as from her brothers and sisters.

I just need to know she's alive, says Caroline Goodall of her drug addicted youngest daughter

Mrs Goodall said she called the police on numerous occasions over the years to have her arrested because she "couldn't see anything else I could do".

The mother-of-three said: "It's the not knowing. You don't know where they are, what they're doing or what they're using. It's all uncertain.

"They lie about anything and everything - it's 100% deceit. You get to a point where it's either you or them."

She said she had no "second thoughts" and no regrets about shopping her daughter because of the desperate situation she was in.

But she added: "If you can handle it at home with discipline, then deal with it."

She said the judicial system needed to be "much, much tougher" on young offenders.

Mrs Goodall said she had learnt to block out thoughts of her youngest daughter over the years as a defence mechanism, admitting she would otherwise "be in pieces in minutes".

"I know she's alive because I ask people who know people and they've seen her," she said.

"I don't need to know where she is, I just need to know she's alive."