Analysis: Can the net migration target be met

- Published

Study is the most common reason for immigration into the UK

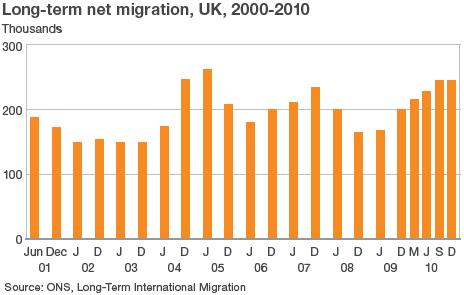

New migration figures, which show that 239,000 more people arrived in the UK than those who left - pushing net migration up by 21% - need to be completely unpicked to understand what is going on.

Certainly it would be unwise to look at those headlines and draw any conclusions as to whether the coalition government has any hope of hitting its ambitious target to bring net migration down to tens of thousands over the course of the Parliament.

Everyone in government knows that the target is a huge challenge.

But today's figures point to two really important elements of the equation which the government cannot control: emigration and European workers.

Immigration has been broadly stable since about 2006, bobbling up and down at just over half a million people a year.

But while immigration has stayed broadly the same, the figures show that fewer people are emigrating.

In the year to December 2008, a massive 427,000 people left the UK. The following December that number fell to 368,000 - and by end of last year it has fallen again to a low of 336,000, the lowest figure in almost a decade.

And it's the changing balance between those arriving and those leaving that led to the 21% rise in net migration - even though the numbers actually arriving have hardly changed.

Of course, emigration does include some foreigners who have previously settled in the UK and then decide to move on. But it is the movement of British nationals which has a bigger effect.

In the year to December 2010, about 124,000 British citizens left the UK to live abroad. That's not a statistically significant change on the year before - but it is about 70,000 down on the numbers who were going before the credit crunch.

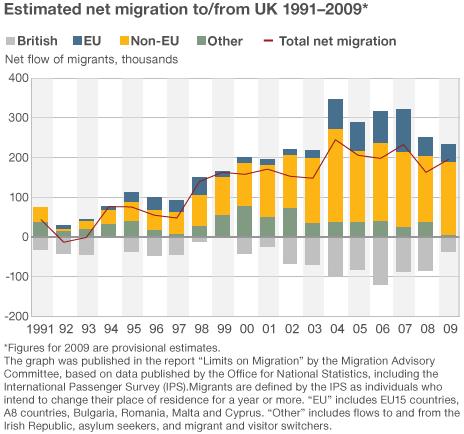

For years, net migration has hardly been affected by the movements of European Union citizens largely because the number of EU workers arriving has been offset by the numbers leaving, including British citizens.

But now, while fewer British citizens are going abroad, more EU workers have been arriving than leaving, particularly from the Eastern and Central European "A8" nations - the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

During the recession, the number of A8 workers crashed - and at one point more were leaving than arriving. But very quickly, that trend reversed.

And although many parts of the UK have got used to the sight of Eastern European workers, their numbers have continued to rise rather than level off.

Figures compiled by Oxford University's Migration Observatory, external, an expert group, show that earlier this year there was a record 651,000 of these workers working in Britain. That figure is important not just because it's high, but because it shows how migration changes rapidly - making medium-term bets on the trend rather tricky.

Dr Carlos Vargas-Silva, senior researcher in the Oxford team, said: "The UK clearly remains an attractive destination for migrants from A8 countries.

"Despite all EU member states having had to open their labour markets to A8 workers, the factors that created the initial pull for A8 workers to the UK are still in place.

"There is a demand for their labour, wages are still much higher than Poland or other A8 nations and there are now well-established A8 communities and networks here to help new and returning EU migrants find a job and negotiate the complexities of life in a new country.

"This adds up to the likelihood that the UK's population of Eastern Europeans will continue to increase for some time, as there are no signs on the horizon that the overall trend of positive A8 net-migration to the UK will end soon."

And that's why this plentiful of supply of cheap and mobile Eastern European labour is a headache for ministers. Their continued arrival, combined with the current falls in the numbers of all people emigrating, mean the government has to look elsewhere to hit the net migration target.

The three current key components of the target policy are a cap on visas for workers from outside Europe, massive curbs on foreign students and a plan to limit the number of migrants claiming a place in the UK for family reasons.

Migrationwatch UK, the campaign group which wants numbers cut, says that ministers have a problem. Its view is that the current policies don't go far enough and the government has to "face down" vested interests.

It says the government has to, for instance, increase departures by making it much harder for people who have arrived on work permits to eventually settle.

Immigration Minister Damian Green says the government is now "operating on all routes" and the effects of the policies will be felt in the years to come.

But even if these policies work, there may be unintended consequences. A recent survey by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, external found that about a third of employers would simply work around the work visa cap, by recruiting freely from the EU.

Dr Vargas-Silva says: "Regardless of the reductions in non-EU net migration achieved by Government policy, there will always be fundamental uncertainty about whether any overall net-migration target will be hit.

"This fundamental uncertainty cannot be reduced unless the target is reformulated to apply to non-EU migration only."

- Published30 June 2011

- Published23 November 2010

- Published14 April 2011