'Shoebox homes' become the UK norm

- Published

Developers say squeezing more houses into available space makes them cheaper

Britain's new-build homes are the smallest in Western Europe and many are too small for family life, says a new report, external by the Royal Institute of British Architects (Riba). But what is living in a "shoebox house" like? And can small mean beautiful when it comes to your home?

Retired sisters Susan and Dorothy bought their newly-built three-bedroom house on a private estate in Devon four years ago. But they are already regretting their decision and are trying to sell up.

Says Susan (not her real name): "We made a big mistake when we bought it. They call it a three-bedroom house - but really it's only big enough for two."

The largest "double bedroom" is just 3.4m (11ft 2in) by 2.5m (8ft 2in), with barely enough room for a double bed.

"It has a fitted wardrobe and I can just about squeeze in in a little chest of drawers," she adds. "But there's no room for even a little chair to hang my clothes on overnight."

The other two bedrooms are even smaller and downstairs the picture is the same.

Says Dorothy: "There is just a small kitchen and a lounge-diner which means that there isn't enough room for furniture or for space to eat and relax."

The sisters sold their comparatively spacious two-bedroom house in Croydon to move to their current property - but found there was no room for many items of furniture, including their bookcases and scores of their cherished books, most of which ended up in charity shops.

Susan describes the cramped conditions that she shares with her sister as "oppressive".

"We are just on top of each other the whole time. We find we are arguing much more than we used to - simply because there's not the space to be get away from one another."

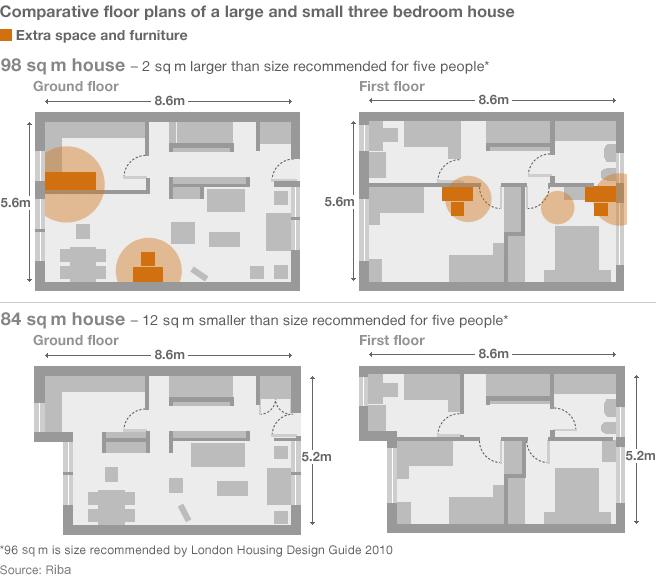

They are not alone - Riba estimates the floor area of the average new three-bedroom home in the UK is 88 sq m (947 sq ft) - some 8 sq m (86 sq ft) short of its recommended space.

Riba's survey of new-home buyers in 2009 found that more than half (58%) said there was not enough space for furniture they owned, or would like to own. Nearly 70% said there was not enough storage for their possessions.

Families reported they did not have enough space to socialise, entertain guests or spend quiet time in private, with 34% of fully occupied households said they didn't have enough space to have friends over for dinner, and 48% saying they did not have enough space to entertain visitors at all.

And houses are getting smaller. The average UK home - including older and new-build properties is 85 sq m and has 5.2 rooms - with an average area of 16.3 sq m per room.

In comparison the average new home in the UK is 76 sq ms and has 4.8 rooms with an average area of 15.8 sq m per room.

The Home Builders Federation, representing the biggest house builders in England and Wales, defends the policy of squeezing more properties into smaller and smaller spaces.

"If you increase standards you're going to increase costs," says the federation's head of planning Andrew Whitaker.

'Clever design'

"That's going to mean houses are going to become more expensive and we're already suffering from a lack of affordability for young people and first-time buyers."

While Riba accepts that building larger houses may cost more, it challenges the housing industry's claim that building bigger will price many out of the market altogether.

It quotes Greater London Authority (GLA) research that found that a 10% increase in the size of house did not lead to a 10% increase in costs for the developer.

Riba says clever design and thoughtful planning means that even with a bigger floor space it was possible "in the majority of cases" to build the same number of houses.

And it while it isn't arguing for nationwide one-size-fits-all policy, it does back standards recently laid down by the The Greater London Authority for homes built in the capital (see table).

Riba also wants house builders to be more transparent about the size of their properties, so consumers have a clear and unambiguous choice when it comes to buying their homes.

"Micro-build" architect Ric Frankland, from Manchester, challenges the notion that small means cramped with his range of tiny homes designed from his Dwelle. practice in Manchester.

He says: "If the major house builders were to employ excellent designers - and more importantly give them the time they need to come up with good designs - small homes could be much more liveable-in."

A typical "Dwelle.ing" has an open-plan feel, with bright and airy rooms, high ceilings, a clever use of sleeping platforms, and tall ceilings that maintain the illusion of space. They are also extremely energy efficient, Mr Frankland says.

Appliances and staircases are cunningly squeezed into available space and walls are easily detachable, so home-owners can create an open-plan feel - or divide living space into more rooms if they choose.

Says Mr Frankland: "I compare our houses to a modern car engine: the most possible parts fitted into the least possible space; but still working better than an old car engine."

Small does not necessarily have to mean cramped

He maintains there are tips and tricks that the housing industry could easily follow - larger windows to open up cramped rooms, and higher ceilings. For example, current mass-produced housing uses the size of a standard sheet of plaster board - 2.4m - to determine ceiling height.

In contrast Mr Frankland says his houses are based around what he terms "a design for living".

"It means we start from the inside out. Rather than start with a floor plan, we ask ourselves what the house will be used for and how can we make it so people will want to live in it."

He estimates that while his houses cost between 10 and 20% more than the mass-produced competition, the extra cost is partially offset over time by energy savings, and by the build-quality of the construction.

His fellow house builders are due to come under the microscope soon with the launch of Riba's Future Homes Commission, which will gather evidence from the industry and consumers and make recommendations to improve housing standards.

Riba Chief Executive Harry Rich says: "Our goal is to build homes in this country that match people's needs. At the moment we don't."

- Published14 September 2011

- Published14 September 2011