Can a spook judge the spooks?

- Published

Miss Zatuliveter had vowed to fight any deportation case

Yesterday I exchanged glances across a room with an alleged Russian spy.

That's not a sentence I ever thought I'd write, but then former MP's assistant Katia Zatuliveter insists she never thought she'd be fighting deportation either.

But it's the manner in which her appeal is being handled that is the really interesting legal story here.

Reporters met Ms Zatuliveter at one of the least understood tribunals in the UK, the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (Siac). It is charged with hearing the Home Secretary's case for deporting the former parliamentary researcher.

The case - the first counter-espionage appeal to come before the tribunal - includes assessments and material from the Security Service, most of which will be heard behind closed doors.

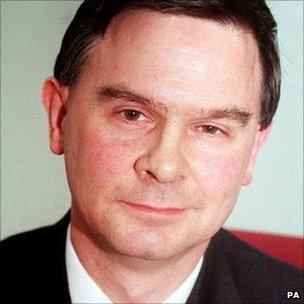

And last night Mr Justice Mitting, Siac's president, ruled that Sir Stephen Lander, the former head of MI5, would be one of the three members of the panel deciding Ms Zatuliveter's fate.

Ms Zatuliveter's legal team think this is outrageously unfair - and they came as close as possible, using measured and legalistic language, to having a right royal row with one of the country's top judges.

Researcher or spy?

The affair broke last December when police arrested Ms Zatuliveter, who was then the aide to Mike Hancock, the MP for Portsmouth South and a member of the Commons Defence Committee.

Sir Stephen Lander: Former head of the Security Service

The home secretary, on advice from the security service, decided that she should be deported because of its view that she was and remains a recruited Russian spy.

Anyone in her position can appeal - and so the case has gone to the strange world of Siac.

The Special Immigration Appeals Commission's environment reflects the limited public nature of its work.

Its hearings are in a windowless basement in an anonymous building in London's legal heartland.

The fact that there's virtually no mobile reception at Siac only adds to the spooky feeling of the place.

Three Wise Men

Putting that kind of conspiracy theory silliness aside, Parliament devised Siac to solve a very particular problem.

How do you give someone a fair hearing when their deportation relies on material gathered by the secret agencies - intelligence that will never see the light of day?

Before the creation of Siac, the government relied on Whitehall officials - "Three Wise Men" - to review secret material and the home secretary's decision to deport.

In 1996, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in a case known as Chahal, external that this system was untenable. The appellant in that case said he faced deportation, having had no opportunity to fairly challenge the secret material.

The government accepted the findings and Siac was the eventual answer, external.

But Siac is no ordinary court process.

There is the "open" case where arguments for and against the deportation are heard in public. MI5 witnesses appear and give evidence - albeit as a disembodied voice from behind a thick curtain.

Then there are the crucial "closed" sessions which examine the national security material underpinning the decision to deport.

It's here that Siac fundamentally differs from the old Three Wise Men approach.

A security-vetted barrister, known as a Special Advocate, is appointed to represent the appellant.

Special Advocates are not the question in the Zatuliveter case - the arguments for and against this system have been well-aired since their creation. The issue is the composition of the panel itself.

The panel comprises a High Court Judge, a second judge with immigration expertise and a third expert lay member whose presence reflects the central feature of the Three Wise Men system.

That third member is usually a former Whitehall official whose career was inside MI5, MI6, GCHQ or the Foreign Office.

Why have such a member? Because Siac says it needs people who can expertly scrutinise the workings and papers of the agencies making the allegations against the appellant. The lay expert is not there to support the government's case - but to test it.

Compromised process?

But Katia Zatuliveter's legal team argue that her forthcoming appeal is compromised because Sir Stephen Lander, who retired from MI5 in 2002, has a vested interest in defending the security service's assessments.

Tim Owen QC, for Ms Zatuliveter, says Sir Stephen is a "cheerleader" for MI5 - who has demonstrated in interviews that he accepts its analysis of how the Russians place spies inside the British state. That means, he argues that he could not fairly assess his client's claims of innocence.

"This is about as clear a case of bias as it's possible to imagine," said Mr Owen. "It's just not fair. It's just not a fair way to proceed. It strikes me as blindingly, obviously unfair."

Mr Justice Mitting freely admits that the tribunal is "rather odd" when compared with the way other British courts operate - but in doing so, he is not conceding that its decision-making is flawed.

"In my judgement an informed and fair-minded observer would recognise that the intention of Parliament was that we should equip ourselves where possible with sufficient expertise to deal with the very difficult and very important questions we have to determine," said the judge.

The allegation of bias, he concluded, was "far-fetched".

So what does Sir Stephen think of all this? He sat throughout the hearing alongside the judge, largely poker-faced, other than the occasional raised eyebrow.

- Published17 August 2010

- Published13 January 2011