Britain: More mixed than we thought

- Published

- comments

How mixed is mixed race Britain?

Looking at some new figures on ethnic minorities in Britain the other day, I glanced at a footnote and suddenly sat bolt upright in my chair.

The implications of it were clear: Britain's mixed-race community must be at least double the size we previously thought.

The research by Dr Alita Nandi at the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) used data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, external (UKHLS) to examine the experience of different ethnic groups in the UK.

As with the census and other surveys, ethnicity is defined in the UKHLS by the individual: if you regard yourself as black Caribbean or white British that is how you are counted.

Using this self-reported approach, the figures suggest that 0.88% of adults define themselves as "mixed".

But the survey - following 100,000 people in 40,000 households - asks another question: what is the ethnicity of your parents?

The footnote puts it: "If we use this alternative definition of mixed then 1.99% of adults are of mixed parentage."

More than twice as many over-16-year-olds are technically mixed race than describe themselves that way.

Underestimated

Self-definition, of course, also applies to under-16s (parents will normally described the ethnicity of their children) and this group accounts for half of the mixed race population.

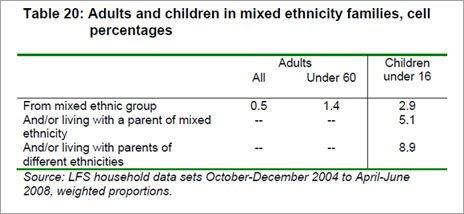

There is research evidence, external which suggests the number of mixed-ethnicity children is also significantly larger than the official figures show.

Self-reported data show 2.9% of children described as mixed race. But the proportion of children living with parents from different ethnic groups or in a mixed-race household is shown to be 8.9%.

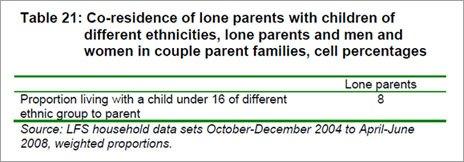

Further support for the contention that the number of mixed-race children is under-counted emerges from work on single parents.

The proportion of children in lone-parent households who are of a different ethnicity to the single mum or dad is 8%.

This suggests to me that there may be around two million mixed race people living in the UK, 3% of the population and therefore a larger group than any of the defined "ethnic minorities".

The most recent estimate from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) is that there are 956,700 "mixed persons" in England, 1.8% of the English population.

Racial mixing is, of course, a controversial subject.

To some it is the welcome consequence of a multicultural society increasingly at ease with different ethnicities. But to others it represents a troubling challenge to national and cultural identity.

I recently went to see the excellent production of South Pacific at the Barbican Theatre in London (sadly just finished) and was reminded how attitudes to mixed race have changed since the musical first opened on Broadway in 1949.

Out of touch

The plot centres around Nellie, a US Navy nurse from Little Rock, Arkansas who falls in love with a French plantation owner while stationed at a military base on a South Pacific island.

It emerges that he has two mixed-race children by his first wife - a fact that Nellie's prejudices cannot initially accept. In the end, however, love wins through.

The show was branded "indecent and pro-communist" in the US southern states, with one legislator in Georgia claiming that "a song justifying interracial marriage was implicitly a threat to the American way of life".

At the Barbican last month, Nellie's disgust at the idea of mixing races seemed shocking in a character otherwise attractive and sympathetic.

They are views quite out of tune with contemporary British values.

The award-winning production is now touring the UK

Nevertheless, long before the eugenics movement gave birth to the horrific idea of "racial hygiene" in Nazi Germany, there have been questions about the wisdom of cultural mixing.

When I was in the Kerala town of Fort Kochi in south India this summer I was shown the thick protective walls built by the Dutch when they controlled the military base in the 17th Century.

Unlike the previous colonial masters, the Portuguese, the ramparts were constructed, not facing seawards to stop naval invaders, but facing the town to prevent soldiers cavorting with the locals.

The Dutch worried more about racial mixing than being attacked.

Given the fast growing mixed-race population, academics have been trying to see whether there are negative consequences to dual ethnic relationships.

The difficulty is in trying to separate out any effects of cultural difference from social and economic impacts.

For instance, while 23% of all children in Britain live in lone-parent households, among mixed-race children the figure is 38%.

Ordinary set-up

On the face of it this might suggest that ethnic mixing makes relationships more fragile.

But it is worth taking a closer look at table 16 in the Equality and Human Rights Commission report, external.

Some 65% of black Caribbean children live in lone-parent households and 44% of black African youngsters.

By contrast, the figures for south Asian children range from 10-15%.

Since 45% of the mixed-race population is white/black and 38% are white/Asian, the figure for mixed children overall is bound to be strongly affected by Caribbean and African attitudes to family life.

The overall figure for mixed race may, therefore, reflect cultural domestic norms rather than the fragility of dual heritage relationships.

Penny Walters wants to fill in cultural gaps for her mixed-race children

Certainly that is the view of Penny Walters, a white single mum who I met in Bristol.

She can probably count herself as an expert on mixed race partnerships. Her six children are from three fathers with three different ethnic backgrounds: three have Jamaican heritage, two have Ghanaian heritage and one has an Egyptian father.

I put to her the question that you are probably thinking right now: "Three key relationships with men from other cultures, all three of them ultimately failed. Are you not living proof that these relationships are less likely to survive?"

Her answer was that the relationship with the Egyptian was "doomed from the start" because his family were Muslim and she could not convert.

Religious difference, she believes, can be a negative factor. But, she said, the failure of her partnerships with the men with Caribbean and African heritage had "nothing to do with race".

They were, she says, both entirely English in their cultural attitudes.

It is an important point.

These days, ethnicity will often have no bearing on a person's cultural outlook.

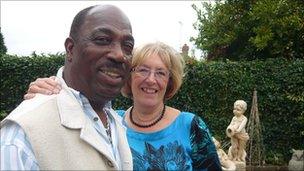

Patrick Olive is a good example. The cool bassist and conga player from the band Hot Chocolate originally came to Britain from Grenada. But, in many ways, he epitomises the traditional middle-Englander.

'Breathing fire and brimstone'

Back-stage at a gig at the Jam House in Birmingham, he revealed himself as a Daily Mail-reading, crossword addict.

At his home in an overwhelmingly white, middle-class corner of Sussex he was keen to show me his "golliwog collection".

"People get too hung up about racism and prejudice," he tells me.

Patrick Olive's band Hot Chocolate, most popular in the 1970s and 80s, is still performing

But Patrick also wanted to introduce me to his wife - a white woman called Jane.

In the mid-70s he recalls how his hopes of dating a white girl were met by hostility and prejudice.

"The father was breathing fire and brimstone," he told me.

A quarter of a century later and his relationship barely raises an eyebrow.

If Britain has become decidedly untroubled by the idea of mixed relationships, the next question is how mixed-race children are faring.

There have been suggestions that dual heritage might bring a double penalty - missing out on support from both white majority and minority communities.

One early indication of this might emerge in the classroom, but new analysis of official education data for BBC Newsnight does not point to a double whammy.

Focusing on the performance of 10-year-olds in English primary schools, the figures look at those who achieve the expected standard across English, maths and science.

Among white youngsters, 77% reach what's called Key Stage 2 or above.

For mixed white and black children the figure drops to 73% - but that's still well above the score for black youngsters (63-65%).

We did find one mixed race group which appears to be thriving. Mixed white and Asian children score 79% - similar to Indian pupils but far higher than Pakistani and Bangladeshi (67%).

Kelly Holmes won Olympic gold medals for Great Britain in the 800m and 1500m at Athens in 2004

In Bristol, Penny's children exemplify the optimism and self-confidence of many people of mixed race in Britain today.

Successful at school and on the sports field (two of her children have played football for Bristol Rovers, one currently plays for Bristol City and her eldest has a business degree), the children tell me they are proud to describe themselves as mixed race.

They are the faces of new Britain - the posterboys and girls for a multicultural nation. Myleene Klass, Lewis Hamilton, Leona Lewis, Mark Ramprakash, Ryan Giggs, Kelly Holmes, Alexandra Burke, Nasser Hussain, Rio Ferdinand.

Recent research suggested that mixed race people are "over-represented at the top level of a number of meritocratic professions, external".

Despite its growth and however you measure it, the mixed race population still represents barely more than 3% of Brits.

But it is increasing fast - and those who predicted a cultural identity crisis have been proved wrong.

If anything, in multiracial Britain, ethnicity is increasingly not the point. Mixed race is mainstream.

Watch the film in full on Newsnight, external on BBC2 at 2230.