In Touch marks 50th anniversary

- Published

- comments

Sue Townsend, Denis Norden and Peter White are fronting the show's birthday celebrations

In Touch, the BBC's radio programme for blind and partially sighted people, celebrates its 50th anniversary this week.

Initially a monthly programme, In Touch first aired on 8 October in 1961 and was billed in the Radio Times as "a magazine with up-to-date news of people, problems and pleasures of special interest to blind listeners".

A special one-hour edition will be on Radio 4 between 1200 and 1300 BST this Friday featuring blind opera singer Denise Leigh and the more recently blind comedy writer Denis Norden amongst others.

Today, in its 20-minute weekly slot, In Touch covers staple issues such as accessible technology, benefits changes and medical breakthroughs but, perhaps less obviously, also has featured blind photographers, skydiving and a memorable April Fools prank about guide pigs being introduced to the UK.

Its longest serving producer, Thena Heshel, describes In Touch as having a "quirky humour". Current presenter Peter White explains: "The atmosphere of the programme is that blindness isn't the end of the world."

In Touch had its first outing on Network Three at 2.40pm on a Sunday in 1961, a little remembered minority interests radio station. It was followed by Italian for Beginners, a programme for chess players and another for lovers of the card game bridge.

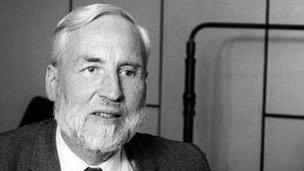

Scott Blackhall 'compered' In Touch for 20 years

Over on the Light Programme at the same time you could hear The Navy Lark, a comedy series starring a young Jon Pertwee and the Home Service had a Sunday Symphony by Beethoven.

The first programme was "compered" by David Scott Blackhall who had been blind for just four years and was a housing officer from Hertfordshire.

He continued presenting the programme until the week before he died in 1981. In the Radio Times, producer Jocelyn Ferguson described him as: "A poet and a mountaineer of the walking and scrambling kind."

In the 30th anniversary In Touch Handbook from 1991, Thena Heshel explained: "It was David's experience of learning to cope with blindness with little or no help from any welfare services that helped to lay the foundations for In Touch guiding principles - to be a programme made by and for blind people which would help them overcome the limitations imposed by blindness at home, at work and in society in general."

At the time, there were few ways in which someone without sight could get information independently. Printed newspapers, pamphlets, posters and books - the traditional ways of conveying information - were not an option and we were still many years away from talking computers and the internet. The advent of radio services in the 1920s had been a godsend.

The importance of the medium as a means of getting information to those who can't see was acknowledged in the Telegraphy (blind persons' facilities) Act 1926, which made blind people - a low income group - exempt from having to pay for a radio licence. Some years later, In Touch was able to bring specific information that could be of direct practical use.

In 1965, the programme upset RNIB when it ran a groundbreaking item about how Americans were being trained to use a "long" white cane which they swept from side to side in front of them.

Mobility lessons for blind people were unheard of back then in the UK and the national blind charity wasn't impressed that the BBC had broadcast information about a method not yet tested in this country; it is of course commonplace now.

The programme has also been a forum for issues that rarely get a wide airing.

"The most important thing we've ever done," says the show's veteran presenter Peter White, "would be about benefits. Blind people, by definition, are often hard up. We know there are big numbers unemployed, people often don't have an awful lot put by and often need it.

Peter White has been the BBC's Disability Affairs Correspondent since 1995

"The progress that was made in the 70s, 80s and early 90s in giving people benefits that took account of the cost of disability was important.

"We played a big part of that. We played a big part in getting mobility allowance for deaf-blind people. It was previously just for people who found it literally difficult to move, like wheelchair users.

"The argument was that while deaf-blind people might be able to move, there were so many difficulties in navigation that effectively you needed the same kind of help."

Off air, In Touch produced the aforementioned handbook which became the blindness bible for social workers. The programme also toured the UK with outside broadcasts and its own mini resource centre in the late 1970s. For a while it hosted a telephone helpline after the programme.

There have been many advances in technology over the last 50 years making the life of a blind person today very different. What we understand as media and information provision now has moved on.

So will In Touch exist in another 50 years? White says no but believes it's still important today.

"The only reason I say that is because at the moment we haven't reached the technological point where people can't do without it.

"Let's face it, we don't know what form radio will take in 50 years. If it lasts, it will have perhaps changed out of recognition. Just looking at what's happened in the last three or four years with access to smart phones, it is revolutionary for blind people, it's as big a revolution as Braille in terms of getting information and it should get easier so that it's not just the blind whizz kids out there who are using them."

White dismisses the idea that blindness may be eradicated in a further 50 years hence entirely negating the need for such a programme in the future.

"Very few cures have been effective. The biggest advance in actually lessening the problem happened in the 1950s with cataracts. You couldn't quote to me many examples. Most drugs around now slow down the onset or keep it stable.

"Stem cells? Well, we're miles away. They say 10 or 15 years; they've been saying 10 or 15 years for ages - mirages. It may happen but I wouldn't hold my breath."

A special one-hour edition of In Touch can be heard on Radio 4 between 1200 and 1300 BST on Friday 7 October, and the usual programme can be heard every Tuesday at 8.40pm on BBC Radio 4.