Why people obey the law

- Published

- comments

Riots spread to several areas of England over a number of days in August

In the last few days I have been sent two pieces of research which, in different ways, try to answer the same question: Why do people obey the law?

Normally, we ask the question round the other way, trying to understand what it is that causes people to break the law. But it is just as interesting and potentially informative to invert the proposition and consider the reasons citizens have for staying on the straight and narrow.

One of the pieces of research, published yesterday, concerned the August riots. Commissioned by the Cabinet Office and conducted by experts from the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen), the report, external was supposed to help government understand the involvement of young people in the disturbances. But, interestingly, the research team also looked at why some youngsters decided not to take part in the rioting and looting.

The research talks about "nudge" and "tug" factors - the tugs being those influences that moved young people away from trouble.

Among the key inhibitors identified was "being occupied through work, an apprenticeship or some other activity". Another was the behaviour of friends and peers: if they were not involved then that was a powerful tug against taking part. And then there was the key role played by authority figures, particularly parents, in preventing a young person from joining in.

"Although some young people barely made a conscious choice at all," the report suggests, "others appeared to have asked themselves one, or both, of two key questions when making their decisions."

What do I think is right and wrong?

What do I risk if I get involved?

The first question is a moral one and the answer people give may be a reflection of the legitimacy felt for the institutions concerned. So, some young people told the researchers they justified their criminal behaviour on the basis that police and government did not deserve their respect.

"There were also young people in all the areas who said they got involved in rioting specifically to get their own back on the police for more general or longer-term grievances. These 'retaliators' saw the riots as an opportunity to 'get one over' on the police and, sometimes, on authority in general:

"People doing it because they're angry at police. Police and people don't have a good relationship and feel mad when get pulled by the police. Government were going to close [swimming] baths and people were angry about this 'cos the only thing for young people to do.' [Young person in custody]"

The second question, however, does not seek to justify behaviour but rather asks whether the gains outweigh the risks. For some young people, it appeared that the scenes on television and the reports from personal texts and messaging encouraged them to believe they could get away with crimes they normally wouldn't consider.

"Assessing the risks: the risks of being caught, what that might mean for your future and whether it was 'worth' it were themes that featured heavily in interviews. A fear of getting caught - through CCTV and DNA evidence, or serial numbers of stolen goods - was a key protective factor for young people. There were young people who made this calculation and decided they would be 'smart' - eg cover their faces. Others said seeing the media coverage, the sheer numbers involved and the police not doing anything made them confident their chances of getting caught were low enough to reduce the risk sufficiently to get involved. A different calculation was made by young people who saw themselves as having too much to lose, even if the attractions were great and the risks low."

Which is more important in encouraging people to obey the law? A fear of getting caught or a belief in the legitimacy of institutions?

The question arises because there are two broad schools of thought on how the justice system should respond to the threat from further rioting and looting as well as crime more generally: get much tougher in terms of punishment and controls or look to improve the relationship with communities to encourage respect.

It is not an "either/or", obviously but there is a balance to be struck because heavy-handed policing may damage respect and undermine legitimacy while few would argue that the way to deal with organised crime barons is for the cops to offer a firm handshake and a smile.

All of which brings me to the second piece of research I have been looking at this week. Professor Mike Hough and his colleague Dr Jon Jackson have been looking at new data from the European Social Survey, external (ESS), a rigorous research project that compares experiences in different countries across Europe.

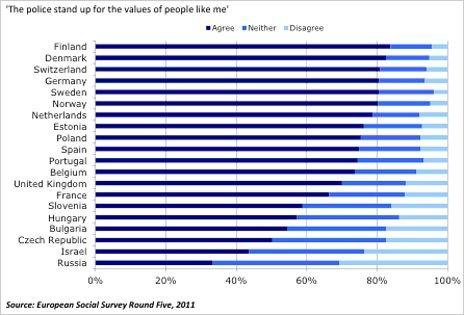

What the latest round of data shows is that there is a range of views on whether the police reflect the values of the wider population.

Interestingly and perhaps surprisingly, around a third of the UK population did not feel they could support the statement: the police stand up for the values of people like me.

Other data on people's attitudes to the police, (whether they act fairly, satisfaction levels, how corrupt people think they are) were analysed, along with information on the levels of punishment, conviction rates and so on.

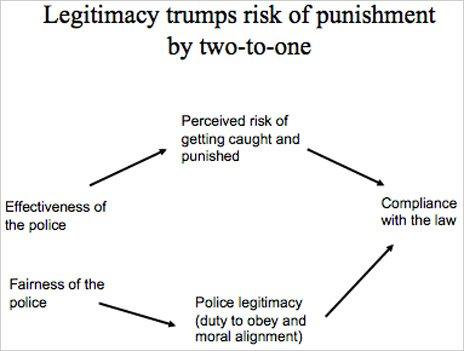

It is still early days with the analysis, I should add, but an initial attempt has been made to assess the relative importance in Britain of punishment and legitimacy in getting people to obey the law. Here is the key slide:

What this suggests, it seems to me, is that both effectiveness and fairness are important - but that if the system is not regarded as fair, people are significantly less likely to obey the law.