Obituary: Sir Terence Conran

- Published

Innovative designer Sir Terence Conran and his groundbreaking Habitat stores were as much a part of the swinging 60s as mini-skirts, The Beatles and Mary Quant.

Later, he brought the same flair to restaurants and architecture, driven by what seemed to be an inexhaustible store of energy.

But his flair for design did not always extend to business matters, and he suffered a number of financial setbacks, including the demands on his purse from a series of failed marriages

Terence Orby Conran was born in Kingston-upon-Thames in Surrey on 4 Oct 1931. His father owned a company that imported products into the UK for use in the manufacture of paints.

In his childhood, he wandered the countryside catching butterflies, something that launched his fascination for collecting anything he found interesting. At the age of 13, he was blinded in one eye when a piece of metal from a lathe hit him in the face.

It was while at Bryanston, the Dorset public school, that he first showed a talent for art and gained a practical knowledge of working in wood and metal.

He went on to the Central School of Art and Design, where he studied textiles, but left after 18 months to take a design job with a company that had been commissioned to work on the 1951 Festival of Britain.

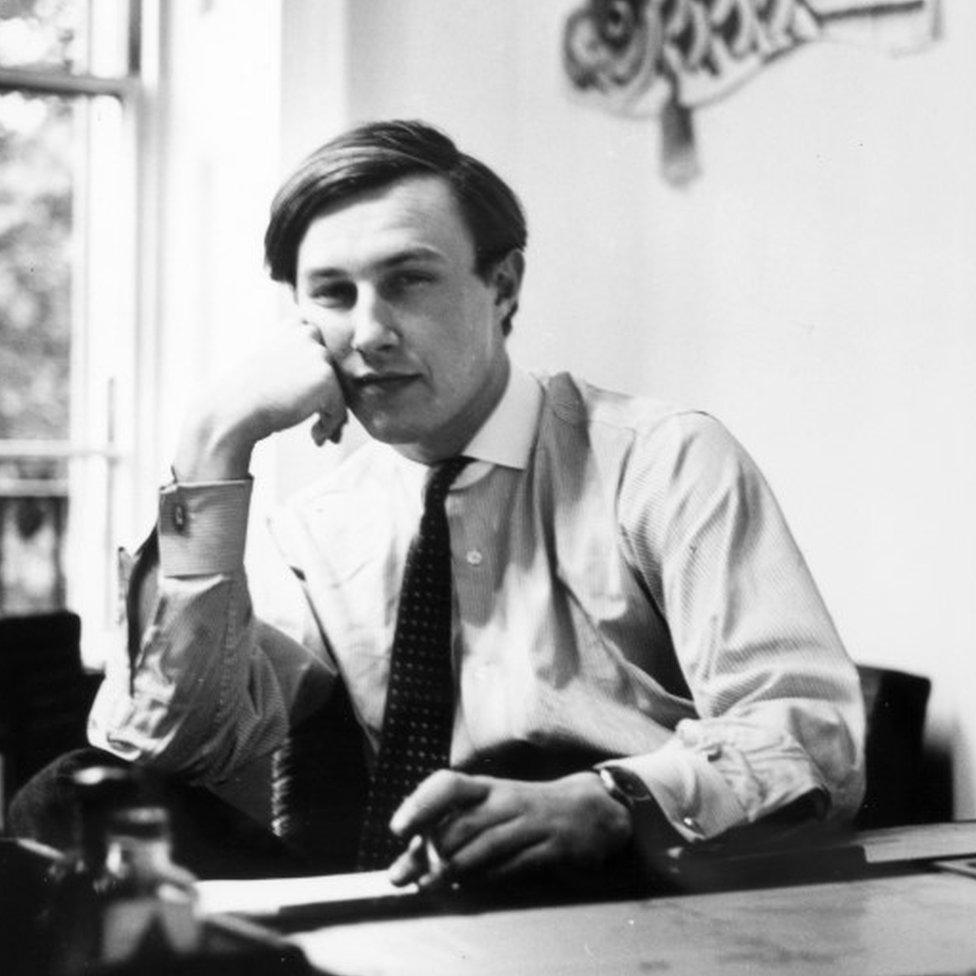

By the mid 1950s he was an established designer

It was to be the only time in his life when he worked for someone else. A year later, he founded the design group Conran & Company and considerably raised his profile when he was asked to lay out the interior of Mary Quant's second Bazaar shop.

He also branched out into catering, with the opening of his first Soup Kitchen restaurant in 1953.

He quickly gained a reputation as something of a taskmaster, and frugal to boot. He rarely took holidays and was reputed to go through the wastepaper baskets in his offices at night for pieces of paper on which had only been used on one side, putting them back onto desks for the next morning.

By the time Conran & Company had morphed into the Conran Design Group, his stylish furniture was beginning to find favour with a new, upwardly mobile, metropolitan middle-class.

Terence and wife Shirley Conran in 1955

He was also on his second marriage. Having wed and divorced the architect Brenda Davison within the space of a year, he embarked on a second marriage to Shirley Pearce who, following their divorce in 1962, went on to become the successful author of books such as Lace and Superwoman.

A year after his third marriage, to Caroline Herbert in 1963, Conran, frustrated by what he saw as the inability of retailers to market his furniture designs properly, opened his first Habitat shop in London's Fulham Road. Two decades before Ikea arrived in the UK, it brought style and simplicity, not to mention flat-pack furniture, into British homes.

Habitat furnishings and household goods were practical and elegant, distinguished by bright colours and copious use of pinewood.

His aim, he said, was to democratise good design; he wanted to make it affordable, once suggesting that he aimed his merchandise at "someone on a teacher's salary".

Pop art

Customers were soon flocking to his stores to snap up modular shelving and soft furnishing splashed with bright pop-art designs.

He was the first in Britain to sell duvets, after experiencing the delights of using one while on a trip to Sweden, and he was a huge fan of the cook and culinary entrepreneur Elizabeth David.

Conran himself, always immaculately turned out, became part of the scene in swinging London - as the city led the world in design, art and music.

In 1974, he published The House Book, which advised its readers how to plan and design a modern home.

Healthy ego

The Habitat chain eventually formed the nucleus of a retail empire that grew to include first Mothercare, then Heals, Richards Shops and British Home Stores. Conran was chairman and chief executive of the group, which was named Storehouse. His success saw him awarded a knighthood in 1983.

But recession hit and profits started to fall. Sir Terence lost control after a boardroom row and walked out in 1990, losing Habitat but retaining control of the Conran brand.

Later he was to say that the different cultures of the various businesses had caused problems - his critics said he was a good designer but a bad businessman. The group later broke up.

But Sir Terence himself stayed in business as a hands-on proprietor. After his ejection from Storehouse, he took with him a single shop, also called Conran, which was rather more upmarket than Habitat. In due course, a second Conran store opened in London, along with eight more in four other countries.

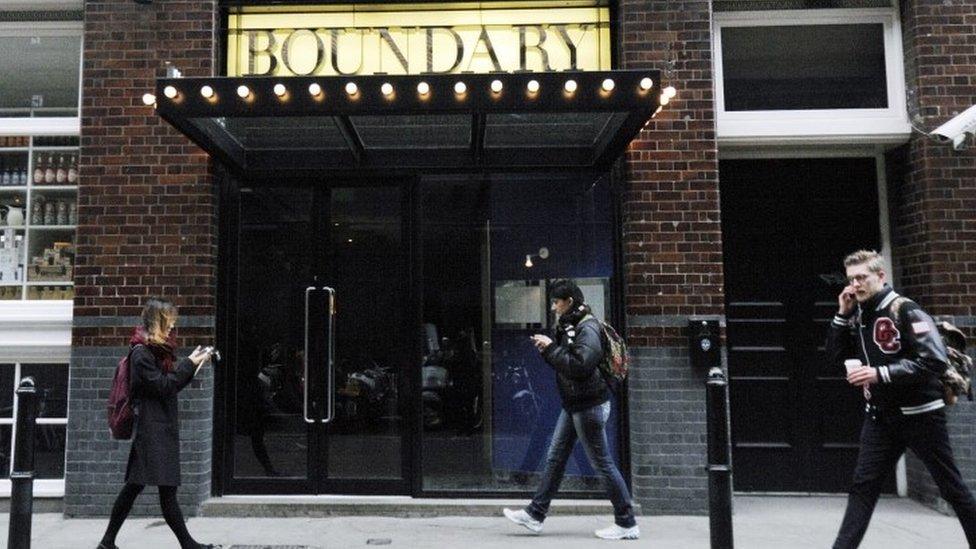

The Boundary restaurant in Shoreditch was one of a string of upmarket eateries

He also launched a private property company, Butlers Wharf, on the river Thames at Tower Bridge, converting a complex of listed warehouses into offices and riverside apartments. But the company went into receivership in December 1990, and Conran lost about £6m of his own money.

He also ran his own architecture and design practice; in 1989 helped found the Design Museum, which was managed by the Conran Foundation; and opened a string of upmarket restaurants - starting with Bibendum, which launched in Chelsea's Michelin House, formerly the headquarters of the tyre firm.

In 1996, he divorced his third wife, Caroline, after she left him for another man. The high-profile divorce settlement centred on how important a role she had taken in running Habitat and the restaurant business, and how much of his fortune - then estimated at £80m - she was therefore entitled to. The judge awarded her a £10.5m settlement, commenting that "it can be difficult for a man with a healthy ego who has achieved vertiginous success to look down and discern a contribution other than his own".

Sir Terence married the interior designer Vicki Davis in 2000, although his children only learned of it after the event.

He continued to open a series of upmarket restaurants and, at the age of 79, returned to his beginnings in mass-market retailing by designing a furniture range for Marks & Spencer.

He was named as a Companion of Honour in the 2017 Birthday Honours.

A driven, often difficult man, Sir Terence's revolutionary ideas for new and colourful designs coincided with the end of post-war austerity and the explosion in culture and art which typified the 1960s.

A new generation of young and more affluent consumers was looking for something exciting and utterly unlike anything their parents had. Terence Conran was on hand to provide it.

"It's thrilling as a designer when you see something you've designed and built actually being used," he once said. "Seeing a shop filled with people, or a restaurant with people smiling away happily, it's like, gosh, all my dreams have come true."