How close are we to a crash-proof car?

- Published

- comments

Every year, 1.3 million people are killed and 50 million injured on the world's roads. Carmakers are racing to create a vehicle that will never crash, but can it be done and will drivers accept a computer that overrides their driving?

Less than 30 years ago, "clunk clicking" ourselves into our car seat belts seemed like the cutting edge of road safety technology.

Since then, we've seen airbags, anti-lock braking systems and crumple zones fitted to new cars.

Now the arrival of crash avoidance technology - systems that can alert drivers to danger and even take action to prevent accidents from happening - promises to cut the number of crashes on our roads.

So confident is Volvo of the power of its technology, it has pledged that beyond the year 2020, <link> <caption>no-one will be killed or seriously injured in one of its new cars</caption> <url href="http://www.volvocars.com/intl/top/about/corporate/volvo-sustainability/safety/pages/default.aspx" platform="highweb"/> </link> . In essence, the Swedish manufacturer is aiming to build a vehicle that will fully protect its occupants and crash less.

"The major cause of crashes is the driver not paying attention or drivers being distracted. This technology is giving cars eyes and knows when the driver fails," explains Thomas Broberg, Volvo's senior technical adviser for safety at the company's research centre in Gothenburg.

Other carmakers are making similar commitments. Toyota says it is aiming for zero fatalities and injuries, although it has not yet said when that goal would be achieved. And Ford is already marketing its new Focus - with its self-proclaimed "intelligent protection system" - as one of the safest vehicles on the mass market.

So what is the latest technology and can it really prevent crashes?

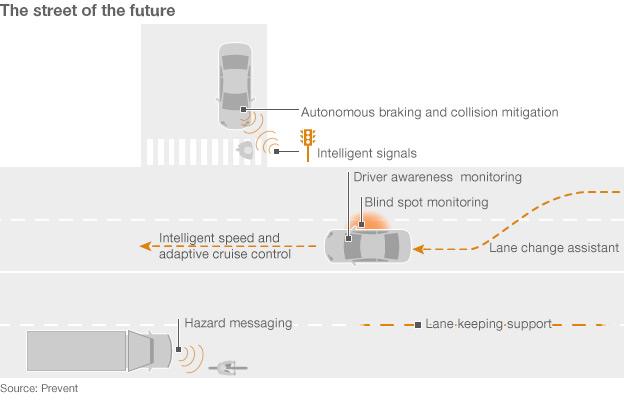

Systems that monitor blind spots and track the alertness of drivers, and electronic stability control - which can detect and help prevent a skid - are already being introduced to many new vehicles. Some cars also now have adaptive headlights that improve night-time visibility by pivoting around bends, as well as instruments that warn of a potential collision or when a vehicle drifts out of a motorway lane.

With <link> <caption>up to 70% of crashes in the UK caused by driver or rider error</caption> <url href="http://assets.dft.gov.uk/statistics/releases/road-accidents-and-safety-annual-report-2010/rrcgb2010-04.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> , these measures are widely expected to help reduce the number of collisions.

One study by the US Insurance Institute for Highway Safety has estimated that four of the currently available features - lane departure warning, forward collision warning, blind spot detection and adaptive headlights - could prevent or mitigate one out of every three fatal crashes and one out of every five crashes that result in serious or moderate injury.

While most people would welcome measures that assist motorists to make wiser decisions, systems that actively intervene in the driving process cause more controversy.

Research is being done on autonomous braking technology, which can stop a car when other vehicles or obstacles get too close, and lane-keeping support, which applies a correcting force through the steering if the driver drifts out of their lane.

The manufacturers are also developing adaptive cruise control, which can automatically maintain a safe speed and distance from other vehicles, and intelligent speed adaptation, which can, in its most active form, prevent a driver exceeding the speed limit.

Research into effectiveness is in its infancy. A 2008 EU study by the Finnish VTT Technical Research Centre found the most promising technology after electronic stability control - compulsory in new cars in Europe - was a system preventing a driver straying from a motorway lane. It <link> <caption>estimated that they could reduce deaths by about 15%. </caption> <url href="http://www.vtt.fi/whatsnew/2008/20081209.jsp" platform="highweb"/> </link>

The same researchers found that functions warning drivers they were exceeding the speed limit and of other potential hazards would cut fatalities by 13% and that emergency braking assistance and driver drowsiness warnings could potentially reduce deaths by 7% and 5% respectively.

However, other studies have been more optimistic. The US Highway Loss Data Institute found that <link> <caption>27% fewer insurance claims were made against cars fitted with Volvo's City Safety system,</caption> <url href="http://www.iihs.org/news/rss/pr071911.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> which uses autonomous braking technology to avoid front-to-rear low-speed crashes. And University of Leeds research has found that speed-limiting technology <link> <caption>can reduce crashes causing injuries by almost 28%</caption> <url href="http://www.lowcvp.org.uk/assets/presentations/Oliver%20Carsten%20-%20Institute%20of%20Transport%20Studies%20Leeds%20Univ.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Technology that removes decision-making responsibility from drivers remains contentious.

Critics argue that a motorist who is required to do little to keep his or her vehicle on the road is not likely to be an alert and safe driver. The Association of British Drivers believes <link> <caption>all technology that takes responsibility away from the motorist should be prohibited</caption> <url href="http://www.abd.org.uk/resources/documents/transcom_roadsafety_2008.htm" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

"We have to be confident that the engineering can cope with a range of complexities in the same way as a human," explains Peter Rodger, the Institute of Advanced Motorists' chief examiner and former Met Police traffic inspector. "This is quite a leap of faith for me to take."

Rodger, like others, questions how a driver unaware of the road environment around them would be able to take control when the equipment fails in an emergency situation - something widely known as "automation-induced complacency".

"How do you manage the transfer from one [automated system] to the other?" he asks.

Increasing the role of technology also throws up questions about who is liable in the event of a crash, Rodger suggests.

"Who is responsible - me, the car manufacturer or the software engineer?"

Some believe the solution to these problems is actually letting computers take over driving completely. Fully intelligent vehicles that can "see" and communicate with other vehicles and the road environment.

The US National Highway Transportation Safety Administration estimates <link> <caption>81% of all light-vehicle crashes involving unimpaired - or non-drinking or drug-taking - drivers could be prevented by intelligent vehicles</caption> <url href="http://www.nhtsa.gov/DOT/NHTSA/NVS/Crash%20Avoidance/Technical%20Publications/2010/811381.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Oliver Carsten, professor of transport safety at the University of Leeds, is among those who believe fully automated vehicles working within an intelligent transport system are the desirable endgame.

"Why not?" he asks. "There are strong arguments for automating motorway driving, which many people find boring and during which time they want to be able to do something else, and which provides benefits in terms of safety and fuel consumption."

He believes multiple-vehicle accidents in difficult driving conditions, such as dense fog, could be avoided if driving were automated.

"The only thing going against it [automated driving] is if you consider the environmental impact. There would be an increase of 50% capacity in automated motorway lanes, which means more vehicles and more fuel."

But such full automation is still a "long way off", he suggests, as is building a car that never crashes.

What most carmakers are now pledging, he points out, is to eliminate deaths and injuries in their vehicles - not prevent collisions altogether.

Back at Volvo, Broberg is keen to reassure motorists that manufacturers are not attempting to take control away from drivers.

But he defends the ambition to override a human being when he or she makes a decision that endangers the lives of others.

"The car is only acting if the driver is not in control - it helps the driver to become a better driver. Should you have the right to be out of control so that you risk someone else? I don't think that's right."