How a king's judges were hunted down

- Published

The Old Church at Delft, where a secret meeting about the outlaws was held

Capturing wanted fugitives and transporting them across borders has been much in the news in the post-9/11 era - the time of extraordinary rendition, instant communications and intercontinental flights.

But March 2012 marks the 350th anniversary of just such an incident, in the Dutch city of Delft - then, as now, a pleasant place with canalside houses and windmills, immortalised in the paintings of Vermeer.

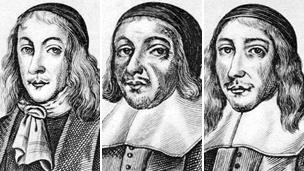

John Barkstead, Miles Corbet and John Okey were "chosen as scapegoats"

In December 1661, a fugitive Englishman wrote to a contact there: "My real friend... [We] intend to be with you about the latter end of February or the beginning of March, and hope then to meet our wives with you."

The writer was John Barkstead, formerly one of Oliver Cromwell's powerful major generals and commander of the Tower of London.

Four months after writing the letter, Barkstead was in London, suffering the gruesome punishment of being hanged, drawn and quartered.

He and two associates, John Okey and Miles Corbet, had been seized in Delft in "a classic example of governments ignoring the clear rules of international law to liquidate their enemies," says human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson QC.

Downing whisked the prisoners out of Delft to an English ship at Hellevoetsluis

The trio were outlawed regicides. Like others executed before them, they had signed the death warrant of Charles I in 1649.

"Somebody had to suffer and so they were chosen as scapegoats," says historian Dr Alan Marshall of Bath Spa University. "It was meant to say, 'This incident is closed for the rest of the nation because we've given these men over to the executioner.'"

The name of the English envoy who masterminded the seizure is still famous.

It was Sir George Downing (1623-84), who created Downing Street in Whitehall by building property there. But, while he is remembered, the Delft incident is largely forgotten.

"In the city archives I found nothing about the incident. It is not even mentioned in the minutes of the meetings of the City Fathers," says Delft's official historian, Bas van der Wulp.

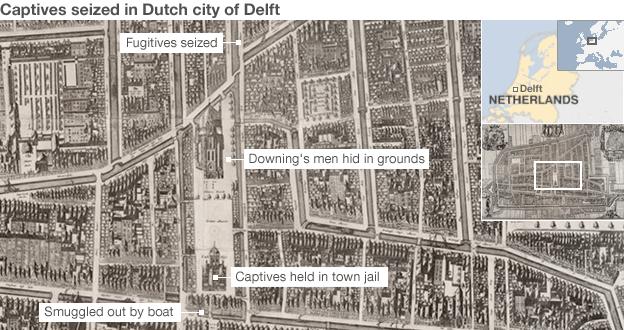

Downing hid his servants in the grounds of the New Church in Delft

At the time many people were shocked by Downing's action - he had been a spymaster and envoy of the Cromwellian government before changing sides at Charles II's restoration to the throne in 1660.

He had started his career in the anti-royalist cause as a chaplain to the regiment commanded by John Okey, one of his victims in Delft.

"He was very clever, very devious... but entirely without morality. I do think it is time to rename Downing Street," says Geoffrey Robertson.

Abraham Kick, Barkstead's English contact in Delft, was Downing's spy. Early in March 1662 he met Downing's associate, Major Miles, in the town's Old Church to inform him that the regicides, as expected, had arrived.

Downing went to Jan de Witt, the most powerful politician in the Netherlands, to ask that the Estates (government) of Holland issue a warrant for their arrest.

Downing kept the location of the fugitives secret from the authorities in The Hague. He himself hurried to Delft with the order. He took a group of his servants and English officers in the Dutch service, and ordered them to hide in the grounds of the New Church.

He promised handsome bribes to the town's bailiff and under-bailiff. When told that the Delft thief-takers were not available he volunteered his own servants to make the arrest.

The party burst into Kick's house, believed to have been in the Nieuwe Langendijk, near where Downing's party were hiding.

The three regicides were smoking pipes and drinking beer by the fire. Corbet, who was not staying with Kick, was about to leave: "A candle was put into the lantern to have lighted him home - so had we come a moment later he had been gone."

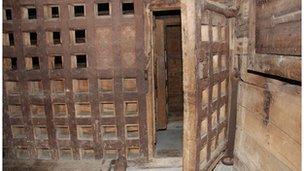

The three were taken to Delft's jail - the ancient tower known as the Steen, built into the City Hall.

The regicides were taken to the town jail, then as now built into Delft's city hall

But the city's magistrates allowed well-wishers to visit the prisoners and public sympathy for their plight was strong. "I was forced to keep some of my servants there night and day," said Downing.

The magistrates wrote to the authorities in the Hague declaring that the three should not be handed over to him.

The wretched regicides still thought Kick was their friend. The magistrates sent him to the Hague to find them a lawyer. Kick went straight to Downing, who warned the lawyer off.

Downing went back to De Witt and secured a warrant for the handover, addressed only to the bailiff of Delft, cutting out the magistrates.

"The bailiff said that he did very much apprehend some rising in the town if there were but the least notice of our intention to carry them away," Downing reported afterwards.

"We resolved in the dead of the night to get a boat into a little channel which came near behind the prison, and at the first dawning of the day... to slip them down the back stairs."

Before five in the morning the boat was out of Delft, and the prisoners were on the way to an English frigate at the port of Hellevoetsluis.

"This is a thing the like thereof hath not been done in this country and which nobody believed was possible to be done," Downing said of his coup.

In the Estates of Holland, wrote the contemporary Dutch historian Lieuwe Aitzema: "People were ashamed, and wished they were a thousand miles away."

The Dutch prided themselves on not giving up fugitives - they had resisted similar demands by France - and there was no treaty or proclamation to say regicides would be given up.

But in that period England and the Netherlands were always either in a trade war or on the verge of one. As Bas van der Wulp puts it, the incident could be seen "as a detail in the complicated relationship between our two countries".

"It's all a matter of power politics," says Alan Marshall, author of a book on intelligence and espionage in the Restoration period.

He adds: "The espionage angle always blurs what you might call normal morality because it then comes down to functionality"... to whether or not an operation was successful.

That was an environment which amply suited Sir George Downing.

John Okey reportedly said on the scaffold: "There was one, who formerly was my chaplain, that did pursue me to the very death. But both him, and all others, I forgive."

The locations where the 1662 drama took place can still be visited today. Picture courtesy of Erfgoed Delft/Archief Delft.