Occupy London: What did the St Paul's protest achieve?

- Published

The Occupy London movement wanted to change the nation's financial sector - but did it succeed?

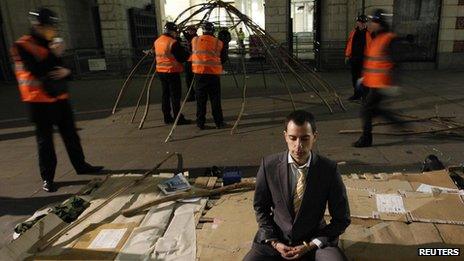

The tents have been packed away, sleeping bags rolled up and the large Buddha in the meditation tent removed. The Occupy London encampment at St Paul's Cathedral has been cleared following a lengthy court battle.

None of this was by choice - it was carried out by bailiffs and police in the early hours of Tuesday once the courts had decided that the encampment should end.

The camp's population, brimming with political zeal and protesting against corporate greed, had high hopes,previously speaking of "another world"where, they said, the nation's finances could be run better than they are now.

There's nothing left of the physical camp, but what of the ideas that lived here? Did they cause any ripples outside of this small community? Or was it all for nothing?

Catherine Brogan, a poet and member of the Occupy movement, said the eviction had not undermined its cause.

"It doesn't matter whether the tents are there or not," she told the BBC, "it doesn't matter if we're able to camp there.

"What matters is we've been able to come together and meet a lot of people who have all formed networks, both nationally and internationally, to make our voices heard against the crisis which the banks have created and the corporate greed."

John Cooper QC represented the Occupy London movement in court and said he had been advising the camp's members "since about 3am" on Tuesday, a little after the clearance operation began.

"Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal accepted that the protesters from the camp had achieved a lot, including a significant effect on the debate on the balance between the rights of public protest and rights generally," he said.

David Allen Green is a City of London lawyer and inhis open letter published in the New Statesman,, externalfor which he is legal correspondent, he expressed regret that the camp had been dismantled.

"You have been a standing reminder that the force of capitalism may not be what its champions say it is," he wrote.

"In my opinion, you have been a useful if colourful corrective to the arrogance and financial vandalism of many who work in the Square Mile.

"You have shown that anti-capitalistic and other progressive protests do not have to be one-day wonders with violent disorder and breathless commentary, but that they can be patient and respectful even in the face of those which you say are destroying our society and our planet."

John Cooper says courts recognised the protest's "significant effect"

Mr Green went on to say that the camp's greatest achievement "was the realisation that those in power can be wrong-footed... by those who are serious and thoughtful about promoting a better world".

Mark Field, Conservative MP for the Cities of London and Westminster, once urged police officers to clear the "third world shanty town" at St Paul's at night, after claims that many of the tents were not being occupied overnight.

He says the camp's members had "incoherent goals".

He added: "Initially they were calling for the end of capitalism, but all they succeeded in was bringing down some of the leading lights in St Paul's.

"They also wanted to get rid of the Corporation of London, which clearly isn't going to happen.

"I'm glad they have moved on, but I'm also glad that at times when we've seen people being shot on the streets of Libya, Egypt and Syria, that our society is open and free enough to tolerate peaceful protest."

Mr Field does believe the Occupy London encampment has "crystallised the unease" surrounding the "increasing polarisation between the major rich and everybody else".

But he added: "I'm not sure there will be any distinct legacy left by the camp. And the Corporation of London needs to work with other landowners in the City of London to see that we don't see any repeat of this sort of protest in the Square Mile."

'Sense of disquiet'

David Skelton, deputy director and head of research at the Policy Exchange think tank, said the protesters "fed from a sense of disquiet from the bulk of the population".

He said they had also "fed into the debate about stagnating incomes among the middle and working class, highlighting the concept of the 99% and 1%. Whether or not that would have come about without the Occupy London camp is another argument.

"Certainly their rhetoric at the start about sweeping changes to the financial sector was unrealistic and was never going to happen."

Dan Hodges, contributing editor of political websiteLabour Uncut, external, believes the Occupy movement was a failure and that it did not get any coherent message across "because they didn't really have a message".

He said: "The great myth about the Occupy movement is that it's in some way leading and driving public opinion.

"In fact it's trailing quite a lot of the way behind public opinion. The protesters say no-one was discussing the banking crisis, excessive corporate salaries or austerity measures for public services until they brought it to the public's attention.

"But those people looking at them saying that were thinking 'what planet are you on?'."

Mr Hodges said the Occupy movement would not be remembered in a year's time and that "people will forget what happened".

He added: "From global warming to anti-capitalism to the legacy of Iraq and freedom in Palestine - you name it, there was a protester for it. I think at best it was an amusing spectacle, at worst it helped to again push the cause of progressive politics to the margins."

- Published28 February 2012