Define Britishness? It's like painting wind

- Published

- comments

Britishness, it is often suggested, is ultimately about shared values of tolerance, respect and fair play, a belief in freedom and democracy.

This has always struck me as pretty insulting to our friends and relations beyond these shores. Such principles matter enormously, of course, but to claim an international patent on virtue might be seen as a little smug.

I do think Britain is a decent and tolerant place, but how confident are we that it is more so than… (flicks through atlas index) the Netherlands or New Zealand or Norway? We have our share of scoundrels and bigots and, in the absence of good evidence, I am not sure it is wise to claim a podium spot in the league of gentlemen.

If Britishness means anything at all it must go beyond ticking boxes of general niceness. While that may make us feel good about ourselves, there is something a bit disturbing about people who stand in front of the mirror marvelling at their perfect teeth. (Perfect teeth, of course, are regarded as thoroughly un-British.)

Others try to get a handle on Britishness through its association with institutional abbreviations: the NHS, the BBC, the WI or the RSPCA. This is a more profitable path because our brand of alphabet soup has a distinctly homemade recipe. The complex flavours of our health service, national broadcaster and voluntary sector come from a unique combination of local ingredients.

Some argue that it is the principles behind free healthcare and licence-funded TV that shape our national character, but arcane funding mechanisms for the delivery of public services across our islands cannot, surely, be the heartbeat of Britishness.

The NHS is significant, not because of its bureaucracy, but because we have such affection for it. The character of the relationship between citizen and state must lie at the heart of any national identity and with Britishness nowhere is it more exposed than when we are naked under a gown on the doctor's examination table.

Close your eyes and recite the letters N H S. What comes to mind?

I see pale green walls and lino-covered corridors, Hattie Jacques in a starched matron's uniform, half-moon glasses on a consultant's nose, HMSO-brown files stacked behind a fierce receptionist, ancient copies of Country Life on a table and a bunch of yellow chrysanthemums. It is, I accept, a dated and cliched vision of British healthcare and yours will be different. But it is in the Rolodex of memory and perception that Britishness has its source.

Let's try the experiment again.

Brylcreem and bow tie: Quintessential BBC?

Close your eyes and recite the letters B B C.

You might see the iPlayer or imagine the sizeable operation that will bring the London Olympics to the world this summer.

But I am going to guess many of you conjured up an image of a chap with Brylcreemed hair in a dinner jacket and bow tie talking in rounded tones into a Bakelite microphone. Perhaps you heard the Blue Peter theme tune or Robert Robinson welcoming listeners to Brain of Britain. The cultural references will vary but they will almost certainly be nostalgic.

The BBC and NHS shape Britishness because they are powerful voices in the oral/visual history of our islands, passed down through the generations and across the classes. But they also possess a quality that is key to defining identity. Other people don't have them.

Let me give you some examples: Belisha beacons, fish 'n' chips, Chelsea pensioners, Highland games, Marmite soldiers, Blackpool rock, Jimmy wigs, Yorkshire pudding, prawn cocktail crisps, red telephone boxes, afternoon tea, the Greenwich pips, a pint of foaming bitter (or, if north of the Border, make that a pint of heavy).

These quirky items are trotted out as iconic symbols of Britain, not because we believe Gilbert Scott's cast iron scarlet kiosk is intrinsically better than other phone booths, but because it is British and, critically, not foreign.

Belisha beacons lighting the way

In a world of satellite TV and global shopping, foibles and idiosyncrasies become endangered and beloved species. As the planet shrinks and cultural cross-currents threaten to wash national identity away, everyone is searching for anything they can call their own.

The question, though, is whether holding up cultural erratics, the bits and bobs of our past that have somehow survived through the ages, tells us anything about our identity. Are we vainly searching for meaning among the dusty relics forgotten in a trunk in the attic?

It is not the items themselves that are the embodiment of identity. A sporran doesn't hold within its pouch something intrinsic about a Scotsman any more than a bowler hat harbours the essence of an Englishman.

When I was a boy, I spent many family holidays on the Isle of Arran. A little cottage in Kildonan, without television or telephone, was a simple retreat for hassled parents escaping frantic lives in 1960s Glasgow. We went crabbing and mackerel-fishing and played French cricket and whist. However, there were days when three young brothers complained they were bored.

My father would scratch his head and announce a treasure hunt. The rules required his sons to run around the place while he relaxed in a chair. Find something with six legs. Bring me something purple. Something which would be useful in a storm. The more difficult the task, the longer he had to snooze. I remember one windy, grey afternoon when he simply asked us to find something interesting.

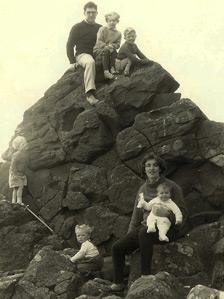

Mark's family holiday in Arran

We scrambled across slippery rocks on the beach and up and down the steep stony banks that surrounded our little cottage. Eventually, we returned with our treasure and laid out our finds for inspection: a bird's egg; a crab's claw; a stone shaped like a rocket; a rusty and anonymous tin washed up with the tide. Which was the most "interesting"? Stones, eggs and claws were fine, but we all had to agree that the label-less corroded can was the winner.

It was just a bit of discarded flotsam, but it was intriguing. Where had it come from? How had it got there? What was inside? It wasn't the object but its mysterious back-story that made it the most interesting item of treasure that day.

That is what we search for in our hunt for identity too. What is interesting about us? It is not tattie scones or pillar boxes that are important in themselves, but their provenance, their survival, their mystery. Our lives are connected through shared experience of objects and events across time and space. Identity is inextricably tied up with heritage and with tradition.

So, my sense of my own identity is shaped by the wobbly cine-films of my brothers and me playing cricket on Arran year after year, the constant presence of Pladda lighthouse and Ailsa Craig in the background. It is the memories I share with my family of annual treasure hunts on the beach: heritage and tradition.

But we must beware these comforting words and where they might lead us. "Identity," it has been said, "is always a modern project: an attempt of differing political and economic interests to construct their historical pasts as the representation of the 'truths' of their present day practices."

The author of that, American sociologist Jonathan Church, spent time on the Shetland Islands investigating what he called "confabulations of community". Confabulation is a wonderful psychological term to describe the confusion of imagination with memory. But Dr Church used it to mean something altogether more sinister - the way in which invented traditions may be used to construct a false identity.

He had gone to Shetland to study the Hamefarin - the homecoming festival first held in 1960 and revived in 1985, which stresses the ancient Viking roots of the people of the islands. It seems like innocent fun, but Dr Church was anxious this new tradition was closing down a more complex historical back-story featuring Scottish kings, German merchants and American oil tycoons. "A singular gaze has become appropriated and institutionalised in the power of official memory," he concluded.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm famously claimed that British traditions "which appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented". A committed Marxist, his assertion that many of the ceremonial trappings of nationhood hailed from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries was dismissed as lefty propaganda by some conservatives. This scrutiny of tradition, holding it up in the light to check its provenance and authenticity, was condemned as thoroughly unpatriotic.

A symbol of national identity?

A few years later, the Labour academic Anthony Giddens described tradition as "perhaps the most basic concept of conservatism", arguing that kings, emperors, priests and others invented rituals and ceremonies to legitimate their rule. The very term "tradition", he said, was only a couple of centuries old. "In medieval times there was no call for such a word, precisely because tradition and custom were everywhere."

I am not an expert on the tradition of tradition.

But Giddens' final point seems true: it is everywhere. Our identity is in tonight's fish supper and this morning's newspaper just as it is in the chimes of Big Ben and the skirl of the pipes. Britishness cannot be nailed down because, like all identities, it is evolving and re-forming with every moment. Trying to define it is like trying to paint the wind.