Everest Olympic medal pledge set to be honoured

- Published

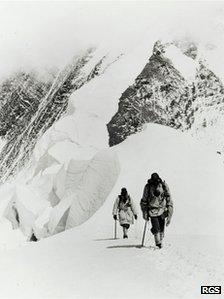

The 1922 team who tried to conquer Mount Everest but failed to succeed

In 1922 a group of explorers made the first serious attempt to climb Mount Everest and, despite their lack of success, their exploits were lauded all over the world - even resulting in Olympic gold medals for them all.

Now, with the London 2012 Olympics fast approaching, British adventurer Kenton Cool has promised to try to fulfil a pledge made 88 years ago to take one of the medals to the summit of Everest.

The 1922 British Everest Expedition team - led by Brig Gen Charles Bruce and Lt Col Edward Strutt - came within 500m of the summit, but failed three times to reach the top.

On the last attempt, an avalanche swept seven Indian porters to their deaths.

Heroic failure

In a letter to his wife, expedition member Dr Arthur Wakefield revealed how he had watched the porters wind their way up a steep wall moments before they disappeared.

The team were given a unique honour at the Winter Olympics two years later

"When I looked back the whole wall was white and there was no string of ascending climbers.

"At first I thought all had been wiped off by the avalanche. But as I kept looking, the fuzz of snow settled down, and I gradually made out most of the figures still on the slope," he said.

Despite not reaching their goal, and recording the first fatalities trying to climb the mountain, the expedition was a popular sensation - a heroic failure.

On a lecture tour that followed the failed bid, team member George Mallory entered the history books when he replied to the question 'why do you want to climb Everest?' with the simple words: "Because it is there."

The team's photographer John Noel even made a short film - entitled Climbing Mount Everest - which toured the country raising money for the next attempt.

The public could not get enough of the men who had come within striking distance of the summit.

That attention climaxed at the1924 Winter Olympics, externalin France when 13 members of the team - 12 British and one Australian - were honoured with medals for mountaineering. It was the first time such medals had ever been awarded.

A further eight of the Olympic medals were presented at a later date - one to a Nepalese soldier serving with the Gurkha Rifles, and seven in honour of the Indian porters killed on the mountain.

The mix of nationalities made the Olympic honour unique - it was the first, and only time a multi-national team had been awarded medals.

At a ceremony in Chamonix, International Olympic Committee chairman Pierre de Coubertin, the father of the modern Olympics, spoke of the team's "absolute heroism on behalf of all of the nations of the world".

Kenton Cool, who is also an Olympic torchbearer, plans to fulfil the pledge made 88 years ago.

In France to collect the medals was the expedition's deputy leader, Lt Col Edward Strutt, a highly decorated officer in the Royal Scots.

As he was handed the medals, Lt Col Strutt pledged to place one on the summit of Everest.

In his memoirs Mr Coubertin recalled the moment: "There was also the moving occasion when, at the foot of Mont Blanc, the medal for mountaineering was awarded to one of the leaders of the famous Mount Everest expedition, a courageous Englishman who, defeated but not discouraged, swore to leave it next time at the top of the highest summit in the Himalayas."

But this was a promise that was never kept.

The 1924 expedition ended with Mallory and fellow climber Andrew Irvine dead on the mountain.

Forgotten promise

In the years that followed, other teams tried and failed to reach the top of the world. During World War II Everest was left in peace.

By the time Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the peak in 1953 the Olympic promise was all but forgotten.

Until now.

"A friend of mine was doing some research into London 2012 when he came across the story of the pledge," said Cool, who has already climbed Everest nine times.

The men on the expedition were commended for their "absolute heroism"

"When he told me about it I said straightaway: 'I have to do that'. And with the 2012 Olympics in London, I knew when I had to do it."

"Then it was a question of finding someone with a medal who would let me take such a precious family heirloom to the top."

"Fortunately, when I got in touch with Charles Wakefield, the grandson of Dr Wakefield, he agreed straight away. I think he's a man who believes promises have to be kept."

Cambridge graduate Dr Wakefield served as a GP in the Lake District and with The Royal Army Medical Corps during World War I before joining the 1922 expedition.

At 46 he was 10 years older than the other members of the team - something he was well aware of.

He wrote to his wife: "I am deeply chagrined to say to say that I am too old for the final summit attack; it seems to me clearly proved that men of 30 to 35 are the right age for this.

"But anyway no man of my age has been higher than me, in fact I am the only one who has stuck it up to 23,000 feet."

"I know for certain where five medals are," said Cool, from Quenington, Gloucestershire.

"And I've got a good idea where to look for a few others, but that still leaves over a dozen of these fantastic medals unaccounted for. I would love to know where they are."

Mr Cool is now preparing to leave for Nepal and, after a few weeks' acclimatisation, hopes to make a bid for the summit, with Dr Wakefield's medal in a special case, early in May.

If he makes it he'll not only have climbed Everest 10 times, breaking his own UK record, but he will have kept a very special promise.

Dr Wakefield's grandchildren did not know anything about the medal until long after his death.

"Talking about the medal would have constituted boasting", his grandson said.

"And Arthur Wakefield most certainly did not believe in boasting.

"The appeal of mountain climbing to him was its pure joy and had nothing to do with medals or honours. "

He added that his family believed that Dr Wakefield would have wanted the medal to go to the summit.

"I also believe that all of the other 1922 climbers would want the medal to go to the top as well.

"I think that bringing one of their medals to the top constitutes a sort of completion of their expedition. "

- Published5 March 2012