MI5 and MI6 secret justice drive prompts debate

- Published

The views on secret justice adopted by some in the UK's intelligence community is at loggerheads with many human rights campaigners

The demand for changes to the UK's justice system has been driven by Britain's intelligence agencies MI5 and MI6, who were left battered and bruised by the Binyam Mohammed and Guantanamo Bay cases.

They argue that the Binyam Mohammed case has affected intelligence sharing with the US and that the civil cases had to be settled without being tested in court.

This, they say, shows a new system is needed.

But it is a view that is being challenged by MPs. The parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights disputes whether there is a sufficient basis for departing from traditions of open justice and moving to a system they see as inherently unfair.

The committee says that the case for change is based on "vague predictions" and "spurious assertions" about catastrophic consequences.

In the Binyam Mohammed case, Britain's spies argued the revealing of intelligence passed to the UK by the US breached the so-called "control principle" in which the originator of intelligence retains control over its disclosure.

Senior intelligence officials maintain that this has led to changes in behaviour by the US in the years since.

US 'unhappiness'

One official told me that in some cases - notably that of a feared Mumbai-style attack just over a year ago in Europe - the US passed the actual intelligence over but withheld some of the details on the source, leading Britain to devote some of its resources investigating it.

But, while officials claim there is greater nervousness from the US, there is no suggestion that life-threatening intelligence has been withheld or that the fundamentals of the relationship have altered.

Critics also argue that American unhappiness over one breach of the control principle is not a sufficient reason for Britain to deviate from its traditions of justice.

They also say that in the Binyam case the judges only released some material because they saw that it had already emerged in an American court case.

The government also points to the settling of a civil claim by former detainees out of court - at the taxpayer's expense - to prevent sensitive material being introduced in court.

They argue that, in such a case, it would be fairer to move to a Closed Material Proceeding where only the Judge and Special Advocates could hear the secret material.

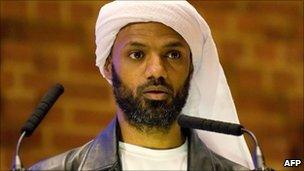

Binyam Mohamed was held in Guantanamo Bay before being returned to the UK in early 2009

They argue this is preferable to the current system where if a Public Interest Immunity (PII) Certificate is agreed by a judge, the material is not considered at all.

But critics argue the PII process has not yet been found wanting.

They also say that even though the new system would allow material to be heard by a judge and Special Advocates, it would not have been tested in open court with the chance for the litigants or their normal lawyer to dispute what was said.

The proposals as currently set out allow the secretary of state to move to closed proceedings when they decide it is in the "public interest".

Critics say this power should be in the hands of a judge - rather than just subject to judicial review - and that the test should be national security, rather than the much broader concept of "public interest".

This seems to be the area where Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg is calling for change.

But opponents of the proposals are suspicious.

Some of them believe that the government deliberately outlined extensive proposals in the Green Paper, knowing it could then be seen to give ground but retain what it really wants - closed proceedings in national security cases.

The critics argue though that it is the very principle of closed proceedings which is flawed.

The government maintains that it is the best way of dealing with cases without damaging security.

- Published4 April 2012

- Published16 November 2010

- Published16 November 2010