Abu Qatada deadline: Why it matters

- Published

- comments

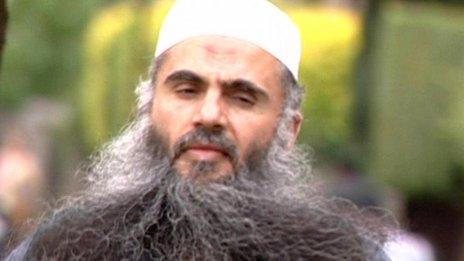

Abu Qatada faces a retrial in Jordan for plotting bomb attacks against American and Israeli tourists

The latest row over Abu Qatada has been a delight for headline writers - but does any of it really matter?

Yes, it does. The question of who was right on the expiry of the deadline is extremely complicated - I'll be writing some more on that later - but if Abu Qatada has secured a final review of his case in Europe, it has the potential to derail not just his deportation but many others too.

On 17 January, the European Court of Human Rights blocked, external Abu Qatada's deportation on one very narrow issue. The judges said he could not be returned to Jordan because he could face a trial that involved testimony against him extracted under torture.

Courts across Europe, including the UK's, have long banned evidence obtained by torture because people will sign all sorts of confessions to stop the pain.

So Strasbourg said Abu Qatada's could be an unfair trial and therefore he could not be chucked out until Jordan had given an assurance that there would be no such evidence in his trial.

Now, it is critically important to remember that Strasbourg ruled that on all other grounds, the British government had the right to deport the cleric because Jordan had given satisfactory pledges that the man himself would not be ill-treated.

So London asked Amman for a copper-bottomed assurance that any possible trial would be fair and free of evidence tainted by torture. And as far as they are concerned, they got that piece of paper.

In the meantime, the European Court clock was ticking. When it gives a ruling, both parties have three months in which they can ask the Grand Chamber, the highest part of the court, to review the case one last time. Once that deadline passes, the judgement stands.

On Tuesday, the home secretary was working on the basis that the deadline had passed and that is why she came to Parliament to brief MPs on the next steps.

In short, the government had accepted the European Court's ruling from 17 January because it had not sought to make an appeal to the Grand Chamber.

That meant if ministers wanted to deport Abu Qatada, they would only need judges to approve of Jordan's new assurance of a fair trial because - and this is the key point - Europe had already signed off on every other element of the deportation.

So, amid all the faff and headlines, the Home Office was in the driving seat. Its top lawyers would take the new assurance to the deportation judge at London's Special Immigration Appeals Commission.

Assuming they won there, Abu Qatada could try to take the case to the Court of Appeal and possibly the Supreme Court but he would have pretty narrow grounds to do so. And that is why the home secretary was in a confident mood in the Commons - even if she wasn't nipping down the betting shop to put a tenner on deportation before Christmas.

But now that's all changed - and ministers are facing a potentially massive problem.

If a case is taken up by the Grand Chamber of the European Court, the judges don't necessarily just look at specific or narrow points of complaint. They can, in theory, look at the entire case.

Theresa May put it this way to MPs on Tuesday, external: "The other option available to us, which is to refer the case to the Grand Chamber… could take even longer and would risk reopening our wider policy of seeking assurances about the treatment of terror suspects in their home countries.

"That policy was upheld by the European Court's judgement in January, and it is crucial if we want to be able to deport terror suspects to countries where the courts have concerns about their treatment. There are 15 other such cases pending. I confirm that the government have therefore not referred the Abu Qatada case to the Grand Chamber."

In other words, a Grand Chamber judgement could go against the UK on any of the grounds in the case - even if those have already been hammered down and dealt with in the past. In the worst-case scenario, it could blow a hole in the government's broader deportation strategy.

That would mean it wouldn't just be Abu Qatada knocking on his prison cell door asking to come out.

In practice the Grand Chamber rarely intervenes or overturns an earlier judgement - but the risk is there, and that's why the referral to the highest part of the European Court is such a big deal.

- Published19 April 2012

- Published17 January 2012

- Published26 June 2014