Why does the UK love the monarchy?

- Published

- comments

I have recently been accused on Twitter of being both a royalist "uber-Toady" and the author of "the most anti-monarchist report you could want to view".

Both tweets related to the same item, a report for the BBC News at Ten that tried to answer a straightforward question: why does a country that has become so cynical about other institutions (Parliament, the City, the press, the police) remain so loyal to the monarchy?

Whatever republicans might wish, less than a fifth of the Queen's subjects in the UK say they want to get rid of the Royal Family - a proportion that has barely changed across decades.

According to polling data from Ipsos Mori, support for a republic was 18% in 1969, 18% in 1993, 19% in 2002 and 18% last year. Three-quarters of the population want Britain to remain a monarchy - a finding that has been described by pollsters as "probably the most stable trend we have ever measured".

Given the enormous social change there has been since the current Queen assumed the throne 60 years ago, it might seem surprising that a system of inherited privilege and power should have retained its popularity.

Crowds show their support as Queen visits Lancashire

But reading some of the comments on Twitter, it seems that even to raise a quizzical eyebrow at the approval ratings of the Windsors is regarded by some monarchists as tantamount to treason.

Republicans, on the other hand, believe that to highlight the conspicuous lack of progress they have had in winning the nation to their cause is evidence of obsequious knee-bending.

I recently re-acquainted myself with the work of two seminal figures in the long-running debate between republican and monarchist thinkers in Britain - Thomas Paine and Walter Bagehot.

I was searching for an answer to the same question: "What is it about our country that we retain such affection for a system which appears at odds with the meritocratic principles of a modern liberal democracy?"

In January 1776, Paine's pamphlet Common Sense, external began to be passed around among the population of the colonies of the New World, a manifesto for American independence and republicanism.

"There is something exceedingly ridiculous in the composition of Monarchy," Paine declared. "One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of the hereditary right in kings, is, that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion."

He contrasted the common sense of his pamphlet's title with the absurdity and superstition that inspired the "prejudice of Englishmen" for monarchy, arising "as much or more from national pride than reason".

To this day, British republicans refer to Paine's Common Sense almost as the sacred text. But monarchists have their own sacred text, written almost exactly a century afterwards. Walter Bagehot's English Constitution, external was a belated response to the revolutionary arguments of the New World republicans.

"We catch the Americans smiling at our Queen with her secret mystery," he wrote, with a suggestion that Paine and his kind were prisoners of their own "literalness". Bagehot didn't try to justify monarchy as rational (indeed he accepted many of Paine's criticisms), but his point was that an "old and complicated society" like England required more than mundane, dreary logic.

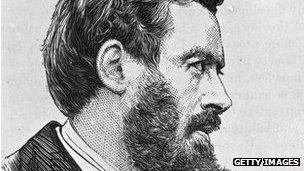

Walter Bagehot wrote about the "mystic reverence" essential to "true monarchy"

"The mystic reverence, the religious allegiance, which are essential to a true monarchy, are imaginative sentiments that no legislature can manufacture in any people," he wrote. "You might as well adopt a father as make a monarchy."

Bagehot had identified a developing national characteristic. As colonial power and the riches of empire declined, there was an increasing desire to define greatness as something other than wealth and territory. Britain wanted to believe it was, intrinsically, special. "People yield a deference to what we may call the theatrical show of society," he wrote. "The climax of the play is the Queen."

Wind the clock forward to 1952 and plans were being made for the Coronation of the new Elizabeth II. Despite post-war austerity, it was decided the event should be a fabulous, flamboyant, extravagant affair with all the pomp and pageantry they could muster. There would be feathers and fur, gold and jewels, anthems and trumpets.

It was a giant gamble. Britain was re-evaluating many of the traditional power structures that had shaped society in the 1930s. How would a population still subject to food rationing react to a ceremony that almost rubbed its nose in the wealth and privilege of the hereditary monarch?

Two sociologists, Michael Young and Ed Shils, had joined the crowds in the East End of London, dropping in on street parties to find out. Their thesis, entitled The Meaning of the Coronation, accepted that there were some who had dismissed the whole affair as a ridiculous waste of money.

Street parties for the Coronation were judged "a great act of national communion"

But overall, they concluded: "The Coronation provided at one time and for practically the entire society such an intensive contact with the sacred that we believe we are justified in interpreting it as we have done in this essay, as a great act of national communion."

Britain - battered, bruised and broke - appeared determined to embrace its monarchy and hang the cost. The paradox is that austerity was positively comfortable with ostentation; institutional challenge spawned a passion for hereditary authority.

It wasn't just that Britain wanted a distraction from hardship and uncertainty. Enthusiastic support for monarchy seemed to run counter to the new liberalism which was guiding the politics of post-war Britain.

The explanation, I think, is that the 1950s were also a period in which the country was anxious about how global, institutional and social change might threaten its identity.

The impact of Americanisation as well as colonial and European immigration upon British life were a source of great concern. Despite winning the war, it appeared that national power and influence were being lost. Institutional authority was being questioned.

There were fears, too, that the values and traditions which underpinned family and community life were also changing rapidly. War and financial hardship had combined to shake up and challenge ancient orthodoxies.

Monarchy represented a bulwark against rapid and scary change.

Sixty years after our Queen assumed the throne, many of those same anxieties remain. Concerns about how globalisation and immigration are changing Britain continue to trouble us. Respect for institutions has declined as the global financial crisis has ushered in a new era of austerity.

In Accrington earlier this month, I watched a down-to-earth, no-nonsense town go slightly mad for the Queen. Thousands lined the streets, hung out of windows, climbed lamp-posts to catch a glimpse of their monarch.

They stood for hours in a chilly wind wearing daft hats - a metaphor for the attitude of their country. Times are tough, the challenges are great and we respond by cheering an aspect of our culture that, for all its irrationality, is uniquely ours.

The British have always chosen the quirks of our history against foreign rationalism. The Romans brought us straight roads and decimalisation. As soon as they left, we reverted to impossibly complicated Imperial measures and winding country lanes.

The Normans commissioned the Domesday Book to try and impose order on bureaucratic chaos but had to compromise at every turn. That is how we ended up with something called Worcestershire - a place that foreigners find impossible to pronounce, never mind spell.

The British don't like straight lines. When we look at those maps of the United States with ruler-straight state boundaries, we feel pity. Walter Bagehot understood that our identity is found in the twists and turns of a rural B-road, not in the pragmatism of a highway.

It is the same with our system of governance. Logic is not the most important factor. We are happy to accept eccentricity and quirkiness because they reflect an important part of our national character.

So in trying to explain the unlikely success of the monarchy, we shouldn't expect the answer to be based on reason.

It is not a pocket-book calculation of profit and loss - how much does the Queen cost compared to what she brings in for the tourist trade?

It is not a question of prevailing political attitudes - how can a liberal democracy justify power and privilege based on an accident of birth?

The British monarchy is valued because it is the British monarchy. We are an old and complicated society that yields a deference to the theatrical show of society.