Bomber Command fliers in their own words

- Published

- We were too young to know what we were doing"

- Dennis "Lofty" Wiltshire

Served in RAF 1939-44

Flew six missions as flight engineer on Lancaster bombers

Flew raids on Bremen, Dortmund and Cologne - Lofty and his air crew

- Wireless operator

Fred aka "Nosey" - Navigator

Reg aka "Maps" - Rear gunner

Nick aka "Tail-end Charlie" - Mid-upper gunner

Tom aka "Piper" - Bomb aimer

Jim aka "Bomber" - Pilot

Lesley aka "Skipper" - Flight engineer

Dennis aka "Lofty"

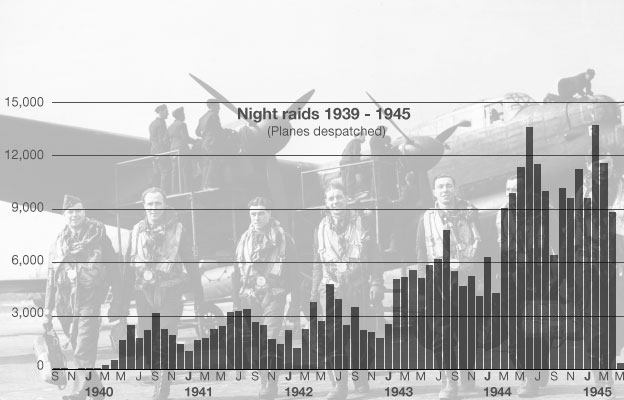

- 125,000 served in Bomber Command

- 55,573 air crew killed

- under half survived first tour in 1942

- one in six survived first tour in 1943

- Bomber Command and main targets in Germany

-

9,000

bombers lost

300,000

sorties

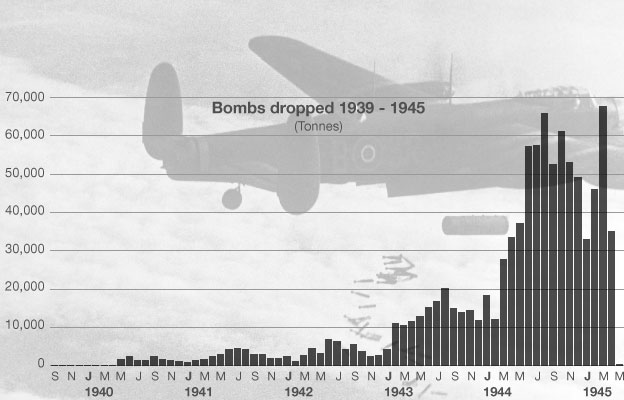

- Bombs

1,000,000

tonnes - Killed

305,000 - 600,000

German civillians - Destroyed

one in five

dwellings - 75

major cities and towns

A memorial to the 55,573 airmen of Bomber Command who died taking the fight to Nazi Germany during World War II is to be unveiled by the Queen. It is an act of remembrance that, for some, will be controversial.

When a Lancaster bomber showers Green Park in central London with poppies on Thursday, it will be the first chance in almost 70 years for surviving crew to formally recognise their fallen friends.

Almost half of the 125,000 Bomber Command lost their lives - more than today's entire RAF personnel - yet their courage dodging night fighters and anti-aircraft fire has never been officially marked until now.

It was their military commanders' policy of large-scale area bombing near the end of the war that drew criticism, stalling progress on a memorial for decades and overshadowing their sacrifices.

Hitler's Luftwaffe had already launched an aerial bombardment campaign on civilians in Poland in 1939, and tried to terrorise London into submission during the Blitz.

The young volunteers of Bomber Command - most barely out of school - destroyed German cities with several "thousand-bomber raids", killing between 300,000 and 600,000 civilians.

It remains a difficult legacy for many veterans.

"At the time, as I thought, I was helping my country and citizens," says Dennis "Lofty" Wiltshire, 93, from Thornbury in South Gloucestershire.

"But when one has had a long time to think about it you think about the people you have killed yourself, and it didn't go down that well. I must admit as an old man I am very anti-war."

Dennis was in his early 20s when he flew six raids as a flight engineer over Bremen, Dortmund and Cologne.

"We were too young to realise what we were doing. We thought we were enjoying ourselves but we were killing people in our attempt to enjoy ourselves," he says.

The young man's life changed forever when his bomb aimer Jim was killed by a shell that struck their Lancaster as they returned from a raid on Cologne.

With fuel leaking everywhere, he tried to help his friend.

'Pig-headed'

"When I got down to him he was bleeding from ears, nose and mouth and as I pulled his helmet off, it was pretty obvious he was gone," he says.

"It turned my stomach right over, and I really went to pieces."

Dennis's remaining crew - pilot Lesley, navigator Reg, rear gunner Nick, mid-upper gunner Tom and wireless operator Fred - returned home safely, but the effects left him with severe post traumatic stress for years to come.

The raids on the likes of Cologne were among the most devastating of the entire war, but were considered legitimate by the allies as all large German cities contained important industrial districts.

In 1939, the Luftwaffe had carried out massive air raids against Polish cities - notably Warsaw, Wielun and Frampol - destroying hospitals and schools and targeting the Jewish Quarter.

And a year later, German bombers hit the centre of Rotterdam to try to force a Dutch surrender. Then came the nine-month Blitz on London and several other British cities.

At least 25,000 died in the allies' raids on Dresden in 1945, which left the baroque city in ruins. And 75 of Germany's biggest cities and towns were destroyed along with one in five of all the nation's dwellings.

Historian and author of Bomber Boys, Patrick Bishop, says the controversial nature of the raids delayed recognition for the young airmen.

"The bombing of Germany was an embarrassment post-war which didn't fit the wartime narrative the allies constructed," he says.

"Although the population very much admired the bomber crews, when the war was over there wasn't a huge appetite for celebrating them."

He says the politicians sensed this, and in a spirit of reconstruction, did not want to "harp on" about how the destruction came about.

But many relatives of those who died have long felt arguments about morality are a red herring.

One, who lost his great uncle, wrote on a forum: "All wars are immoral. This memorial was created almost entirely by people that loved and lost someone very dear to them.

"The British did not ask for WWII, nor did the Polish, French, Dutch, Norwegians and others that acutely felt the German jackboot stamp uninvited through their towns and cities."

There were no campaign medals for Bomber Command and no mention of them in Churchill's victory speech.

And it was not until 1992 that a statue to their uncompromising leader - Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris - was erected in the Strand, central London, amid some protests.

Mr Bishop says almost everyone now agrees the campaign went on too long.

He says it was Harris's "pig-headedness" that bullied everyone into continuing with it, including the wartime leader.

"Churchill was never 100% a devotee of the campaign, but he thought it would be bad for morale if he sacked Harris," he says.

Alan Biffen, 87, from Chichester in West Sussex, began flying Lancasters in January 1945.

He volunteered at the age of 16, claiming to be 17, and was involved in raids on Harburg, Essen, Dortmund, Leipzig, Pilsen and SS barracks at Berchtesgaden.

He says he is "very pleased" so many young lives are finally being honoured.

"We did what we did because we wanted to win the war and get back to peacetime Britain," he says.

"I never think about the number of people my bombs might have killed, you're doing a job, you're told to go in."

He recalls a commander telling him that every operation he flew would bring the war a little bit closer to the end.

"It was such a hell of a long time ago, I'm glad I did what I did and I suppose I'm proud of the little bit I did," he says.

Anti-war group the Peace Pledge Union has criticised the memorial as a "monument of shame" for turning "war crimes" into something heroic.

But Mr Bishop says the controversy today is a "bit contrived", arguing that people understand moral considerations were put aside for the wartime situation.

"Most people accept these men were asked to do terrible things and endure terrible things, it's a national shame their sacrifices weren't commemorated earlier," he says.

Dennis Wiltshire is unable to make the long journey to London to attend the opening of the memorial - perhaps one of the last to the WWII dead - but will watch on television with pride.

He says Bomber Command crews were called the underdogs in contrast to fighter pilots who were known as "superdogs", and he did not ever expect to see the memorial.

"I was very surprised and chuffed about it. The simplest way I can say it, is that it's a thank you to all those fellas that died."

- Published26 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012

- Published4 February 2011

- Published21 May 2012