England riots: One year on

- Published

The widespread public disorder of August 2011 started in London before moving on to other cities, including Birmingham and Manchester

It is one year since riots spread across cities in England in what was the biggest display of civil unrest in the UK for 30 years.

More than 3,000 people were arrested in connection with the unrest, which saw streets in parts of the country awash with looting, arson and violence.

One year on, what are the recollections of those affected and what has been the impact on their lives?

Tottenham post office owner: 'You can't destroy our soul'

The summer riots of 2011 began after Mark Duggan was shot dead by the police.

The 29-year-old father-of-four was shot on 4 August in Tottenham, north London.

Within days riots broke out in Tottenham, which then spread to other parts of London and were mirrored in other cities in England to form the worst disorder of a generation.

The findings of a recent survey suggest police officers caught up in the riots were woefully outnumbered, leaving many fearing for their lives.

Vipin Rao, who runs the post office in Tottenham, set up in a new premises just months after the riots

In Tottenham, the epicentre of the initial disturbances, five buildings were gutted by fire.

The local post office was among the burned out sites.

But within months Vipin Rao, who owns the local branch, had set up again in a new premises nearby.

One year on, he has a message of defiance for those who threatened his livelihood.

"I always wanted to tell people who did the riot that you can destroy the building but you cannot destroy our soul, our willingness to serve the customers, our willingness to serve the community and we will come back again," he said.

Some of the businesses on Tottenham's high street say they still have not received adequate compensation, but the government says the vast majority of claims have finally now been settled.

Meanwhile, Haringey Council has revealed that 5,000 jobs could be created under its plans to revitalise Tottenham.

The plan, which is the council's vision for the area until 2025,, external also involves building 10,000 new homes by 2025.

Hackney resident: 'It brought the community together'

Mother-of-two Graciela Watson could only watch from her window as youths went on the rampage in her road in Hackney, east London.

Youths clashed with police and set bins on fire on what had hitherto been a quiet residential street.

Graciela Watson has lived in Hackney for six years

"At the time it was scary - they were outside our house," she said.

"It didn't feel that their agenda was political. It felt like an excuse to vent frustrations. I think it was a lot of young people having a laugh. Since then it's been fine. There's been no trouble.

"There are still posters up around here and adverts in the Hackney Gazette but I don't recognise any of the youths who were on the streets."

Life quickly returned to normal and "those who enjoy living in the area" united behind the clean-up operation.

"If anything, it brought the community together. One shop was badly damaged and there was a response to raise money for them. Thousands was raised which paid for a new shop front and replaced stock that had been lost."

And the freelance video producer says that, despite last year's unrest, the area she has lived in for the last six years is continuing to change for the better.

"Hackney is going through a huge period of regeneration and there's pride in the area. It's attracting younger, wealthier people to the area."

'Toxteth Against Riots': 'We learned from our 1981 experience'

Jimi Jagne was on the streets of Toxteth in 1981. He was part of the wave of public disorder that swept the streets of inner city Liverpool.

Thirty years later, he was back on those streets for another riot. But this time he was talking to young people, urging them to go home and not get involved in the unrest.

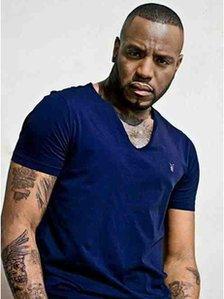

Jimi Jagne was involved in the Toxteth riots of 1981

The youth and community worker was among a group of between 10 and 30 people, called Toxteth Against Riots, who went out on the streets in bright yellow vests over a two week period.

"We wanted to do anything we could to get them off the streets.

"Young people were travelling across the city - across the River Mersey - to cause trouble in Toxteth because of its reputation from 1981.

"We held public meetings attended by up to 300 people and then a small group went out on the streets. We carried on for two weeks because we remembered the previous riots which reignited after a brief hiatus."

Mr Jagne says a separate group, which goes under a different name, was set up following the success of Toxteth Against Riots. It devises initiatives aimed at benefiting young people and has secured funding.

Shop owner: 'Development is key'

Ajay Bhatia runs Machan Express coffee shop, in Birmingham's Jewellery Quarter, which suffered almost £20,000 of damage and lost more than £15,000 of stock during the disturbances.

Mr Bhatia, who was visited by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in the immediate aftermath of the riots, says he had decided to sell his business this May, nine months after the riots.

The pressure of rebuilding his business had started to take its toll.

"It's been a struggle to get insurance claims sorted and rebuild. And business hasn't been good. The bills don't stop - we still have to pay them.

"It's been a big shock mentally, physically and financially.

Ajay Bhatia said 70 looters had targeted his coffee shop last summer

"We haven't had any major problems with the young people since the riots.

"I decided to shut down the business because nobody was coming forward to help us. But the bank has stepped in to provide an overdraft facility and we've been given a small business loan."

But he has since decided to persevere and keep the business going amid signs that development in the area might turn his fortunes around in years to come.

"A new school is opening in September nearby with 200 pupils starting in September and a further 700 next year. It's a two-minute walk away. That will improve footfall. And there are plans to build a new hotel.

"Local development is the key. There has been none in the area for about five years. The government needs to encourage people who want to invest in the Jewellery Quarter. Most of the shops in the area are up for sale."

Youth worker: 'We warned against funding cuts'

"Before the riots we tried to get help to fund our workshops which build relationships between young people and the police through role playing," says youth worker Kelly Reid.

"The workshops give young people the opportunity to speak to the police and ask them about their work, rather than meeting in more volatile and hostile situations.

"We had a team of 12 youth workers which was cut to six last April. We also ran a club for up to 60 young people twice a week which had to close in June last year.

"We warned about the effects of cutting funding. Since the riots we've been able to obtain more funding from the Metropolitan Police, who have been really good."

She says a lot of youngsters she works with, who had been on the periphery of a group but had not actively engaged in violence or looting, were severely punished.

Many who were involved now regret getting caught up in the frenzy, she says - a feeling which is echoed elsewhere anecdotally.

"Everybody has to face up to consequences but a lot of young people were just in the area and now have a criminal record.

"I don't think riots will happen again because the police came down hard on people. The young people know about the consequences of their actions and they know not to act in the same way again.

"Of course, it would've been better if it hadn't happened in the first place.

South Londoner: 'It was like a war zone'

The riots will always remain etched in Kevin Marshall's mind.

His younger brother, an engineering student, was shot twice in the chest during an unprovoked attack in Upper Brockley, south-east London, the day before riots broke out in Tottenham.

Mr Marshall believes the timing of the attack wasn't a coincident. There was already a febrile atmosphere in "certain communities" after Mark Duggan was shot, he says.

Kevin Marshall broadcasts an online discussion show for young people

The London he describes was a tinderbox on the verge of being set alight.

During the riots, the marketing executive from Greenwich, south-east London, regularly travelled through the worst-hit parts of south London to visit loved ones.

He spent time with his brother at a hospital in Camberwell, while looters took to the streets of nearby Peckham, visited his parents at their home near Croydon and checked that his Clapham-based girlfriend was safe too.

"I saw people kicking in newsagent shops and setting cars on fire. It was like a war zone. I felt scared and angry. What do you do if the police aren't doing anything?"

Mr Marshall, 28, said he also felt acutely aware of his race during the riots.

"A year ago people looked at me clearly wondering whether I would start trouble. The riots weren't a black issue, it was a youth issue, but there were clear undertones."

His response was to set up an online discussion programme for young people in his spare time.

Launched in late August, in the immediate aftermath of the unrest, Pandora's Box is broadcast every fortnight.

"It was sad to see youths being allowed to run wild but it made me realise we need to listen to what the kids are saying."

- Published27 March 2012