Empty seats and the privilege of the Games

- Published

- comments

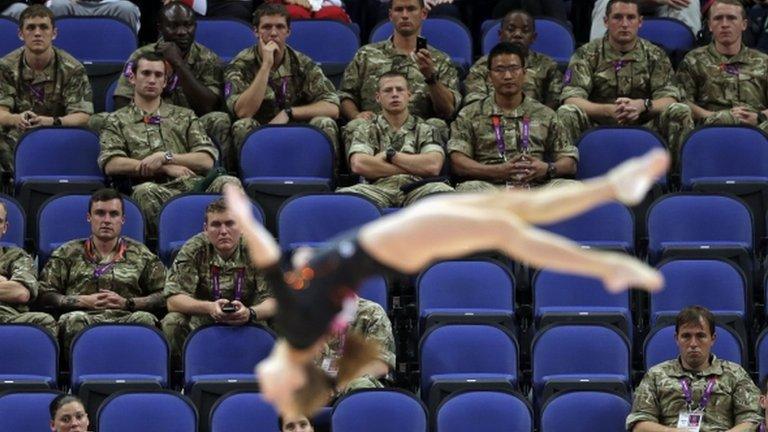

The empty seats scandal at these Olympics refuses to go away. The problem is not simply that each vacant place is a kick in the teeth to the millions of sports fans who have tried desperately to get hold of tickets.

The blocks of empty seating are also a reminder of the privileges available for the rich and powerful at these Games. It looks dreadful because each unused spot emphasises the special treatment afforded to officials and their business partners who then don't turn up.

A quarter of all places are reserved for VIPs as well as the media and athletes, but even at sought-after finals, many of the reserved spots have remained unused.

The head of the British Olympic Association, Lord Moynihan, has said again this week that the empty places are "unfair" to Team GB.

"Every empty seat disappoints me because we need every seat filled to radiate the support from the British public who are passionately interested in sport," he told reporters.

But the issue goes deeper than filling arenas with partisan supporters of the home team. The noble principles of Olympism which govern the Games are based upon a "spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play". It is about setting a good example and showing respect.

Bagsying all the best seats and then leaving them unused, depriving genuine supporters of the chance to cheer on their favourites, appears at odds with the meritocratic ideals which underpin the Games.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) already has something of an image problem in this regard. An article in the New York Times last month headlined Olympian Arrogance, external accused the organisation of being "elitist, domineering and crassly commercial".

For some, the Games are tarnished by the perceived privilege of its organisers. The award-winning Canadian journalist Paul Waldie recently reflected on the "IOC officials living the high life" in London for The Globe and Mail, external.

"A line of sleek limousines waiting at the kerb, armed police patrolling the sidewalk, a block of $2,000-a-night rooms reserved at an exclusive hotel, cocktails with the Queen and a reserved lane on the jammed London highways," he writes. "The entire city seems to be at the IOC's beck and call."

Eight per cent of tickets have been made available to sponsors and 75% to the public. Another 12% go to national Olympic committees and 5% to the Olympic family - people like IOC officials and the media.

The gaps are due to people from a range of those different groups not filling them, the IOC's Mark Adams has said.

And the IOC has also said that it has made great strides to ensure that the Games are an opportunity for men and women for all countries and backgrounds to participate.

But the committee's critics say the fact that 10 of the 105-strong body are princes and princesses feeds a sense of entitlement and makes it less understanding of the concerns of ordinary sports fans.

Our own Princess Royal (one of 33 Olympic competitors on the IOC) rubs shoulders with:

Princess Nora of Liechtenstein

Grand Duke of Luxembourg

Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark

His Serene Highness Prince Albert II of Monaco (Olympic bobsleigh)

His Royal Highness the Prince of Orange

Prince Ahmad Al-Fahad Al-Sabah of Kuwait

Prince Faisal bin Al Hussein of Jordan

Princess Haya Bint Al Hussein of the UAE

Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani of Qatar

Prince Nawaf Faisal Fahd Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia.

The IOC has said it will review the distribution of event tickets and that "everything" about the current system would be analysed.

Given that similar problems occurred at the Games in Beijing, Athens and Sydney, one might be forgiven for asking whether that promise may be as empty as the VIP seats.

- Published30 July 2012

- Published29 July 2012