London Olympics: Who makes the 2012 Games tick?

- Published

Behind the scenes of the London Olympics is a team of people which makes the Games tick. The unsung heroes without whom the venues wouldn't perform and the sports would falter. Who are they and what do they do?

Matthew Millar, underwater cameraman, water polo arena

Hold tight, because there is light in this yarn.

The water polo pool is Matthew's office

"My greatest fear was always scuba diving," says Matthew Millar, a Brit who has lived in Melbourne for the past 20 years.

"Just before my father passed away, he told me to 'dive the world'. I've spent the last four years living and diving in South East Asia and became a dive master there."

"My dad David was a brilliant swimmer. I was always shocking in the water. This has ended up in me being here - it's remarkable and feels like a dream to me."

For a day job, Matt currently dons shorts and a top, goggles, fins, a buoyancy control device (jacket), picks up his gas tank and regulator and dives into the water polo pool on Olympic Park.

He and the team put 11 underwater cameras in the water polo and aquatic centre swimming and diving pools first thing, "babysit" them during the day and put them away at night.

Water polo is a full contact sport. Sit in the stands for a minute and you can see that may also mean "really quite violent". Punching, kicking and swearing are not allowed but it seems everything else is fair game.

A session of matches can leave the two underwater robotic cameras and two fixed goal cameras which capture the action in a bit of a state.

That's when Matt submerges to sort them out.

He adjusts the cameras while staff in the broadcast truck check the picture and confirm it's in position by moving it with a joystick side-to-side for "no" or up and down for "yes".

How has it been, working in the very centre of one of the Olympic venues? Water polo's no big sport in the UK, but the temporary arena has been packed with expats and international fans.

"It's been a sell-out," he says, "So the fans have been a highlight. But my greatest highlight has been to scuba dive in the Aquatics Centre. It's such a beautiful venue, I feel lucky to work in it."

David Lagerberg, raker, beach volleyball

For David Lagerberg, the Olympic Games is all about the pursuit of perfection. How to execute the perfect rake?

Flat side down for the raking, David

"It's about being really delicate with the sand. I'm having to work on not digging potatoes, but just 'shave the face'. That's the best way to describe it," he says.

He's one of the 18 rakers and ball retrievers who work at the Horseguard's Parade beach volleyball venue. They smooth out the sand during time outs and at the end of matches and make sure there aren't mounds of sand in the middle of the court, kicked up by the players.

He rakes under the net, using the flat side, while others clear the lines, so officials can see if the ball falls in or out.

It's a carnival atmosphere at the beach volleyball. There are dancers on court, a TV announcer on the PA and pumped music. The rakers perform their task to Yakety Sax, aka the "Benny Hill music".

Just 18, he's a budding 400m runner who has competed at national and European level. He says the beach volleyball role has proved inspirational. "I know the ovation the athletes get here is 50 times what the rakers get, so imagine what it will be like in the stadium for the GB athletes?"

His best moment? "Stepping onto the court for the first time and that first rake," he says. "It wasn't perfect by any means, but the ovation we got was inspiring."

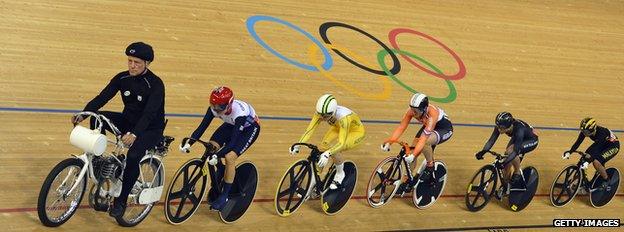

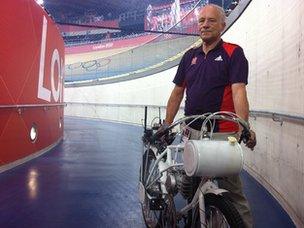

Peter Deary, Derny bike rider, track cycling

The velodrome. Scene of gold medal-saturated British success, wild celebrations and an infamous wall of noise from cycling fans.

Cool and calm: Peter Deary

So what does it feel like to sit up front on one of those odd-looking Derny bikes, named Faith, Hope and Charity, and lead out the riders in the Keirin?

To pace a group of riders including the likes of Victoria Pendleton and Sir Chris Hoy?

"If I started getting all wound up whilst I was down there, it'd be asking for trouble," sighs Peter Deary, deadpan calm.

"It doesn't bother me who's behind. If you started doing that, you'd start favouring people.

"Being a commissaire (he's also a cycling judge), you've got to make sure it's fair to everybody."

It's the kind of composure the track cycling organiser must have looked for when he sought out "someone he knew, he knew had done it and he knew could do it properly" says Peter.

He rides a two-stroke throttle-controlled petrol engine bike during the event, which originated as a betting race in Japan.

He picks up the riders at 25kph and lifts their pace to 45k. He increases their speed by 2.5kph per half lap and drops them off for a 2.5 lap sprint. Then he parks up against the glass around the central floor of the velodrome and watches them race.

A Keirin in the Olympic velodrome, he says, is... the same as a Keirin anywhere. He has to stick to those speed parameters. Make a fuss and you'd mess it up.

His wife, two daughters and three grandchildren were excited to see their 65-year-old granddad zip round the track.

"The kids were going crazy watching," he admits. " So yes, it is special."

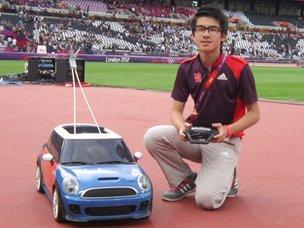

Gareth Goh, remote-controlled car operator, main stadium

Before he has even become old enough to learn to drive, Gareth Goh, 16, is sending cars, albeit remote-controlled ones, up and down the field of the Olympic Stadium.

Forward and back, left and right with the controls

He collects the discus, hammer and even javelin that athletes have thrown down on the grass, and returns them to event officials.

The car is about a metre long, meaning the javelin sticks out, secured in a holder on the top. And the shot is carried back - it doesn't travel far enough to need a lift.

Gareth was there, ferrying javelins, when Jessica Ennis was on her way to winning Heptathlon gold. "It was a great moment, it was certainly something special to be part of when she produced such a great performance," he says.

At the start of each day, he and the team drive the cars out of their special store room/garage and out across the track.

The controls are simple, just forward, back, left and right. But the cars can pick up some speed, and there have been a couple of moments of confusion where drivers have had their eyes on the wrong vehicle and pushed "go".

But the role means Gareth could stand centre stage when the world's fastest man, Usain Bolt, won the 100m final - as the men's hammer competition was also taking place.

"I feel really privileged to have had this opportunity," he says, "especially during the weekend and during the middle of the 100m final. We're doing our job but also can realise what's happening around us."

Joseph Edney and Rachael and Sue Dale, jump ropers, basketball

Joe Edney, from North Carolina, cried bitter tears the first time he was made to "jump rope" at Summer Camp. "I hated it," he says.

Ready to play at the Basketball Arena: Joe and Rachael

But listen-up, budding athletes, he won his first who-can-jump-for-the-longest competition and that feeling was so addictive he now plays to 12,000 capacity crowds at a venue in the centre of the Olympic Games. Every half time break, every day, for two weeks.

The basketball arena in full swing has been compared to a rock gig. Music pumps, the lights flash, and when the sporting action stops, the Get Tricky jump rope team takes to the floor. The venue throbs.

The tools of the trade are plain plastic freestyle and beaded ropes and they knock out tricks, flicks, handstands and push ups. All while skipping.

Tunes such as Hot Right Now, Gold Dust and Pump It blare out.

The team was set up by Sue Dale, whose daughter Rachael is one of the 13 performers drawn from the UK, the US, Belgium and Brazil. They were signed up after going down a storm at the test events before the Games began.

"It's a mixture of different elements - gym, dance and skipping," says Rachel. "The adrenalin keeps on going because it's an amazing experience to have the crowd behind you and cheering you on."

"I can pull out a rope and make someone's jaw drop immediately," adds Joe.

Of their experience being the centre of attention at the Basketball Arena, Rachael says: "It's what we expected and more. This is one of the most important things in the world right now, and we are involved."

Katy Mitchell, mopper and ball retriever, volleyball

Volleyball. It's a sweaty business. So much so that at any one time six synchronised moppers and two "quick moppers" are poised court-side to pick up Olympian drips.

It's synchronised mopping and ball collection at Earls Court

When the court gets wet, players start sliding around. That's dangerous, so during the game, the quick moppers are ready with their towels.

During "time outs" Katy is one of the six big moppers, wielding a flat-headed mop a metre long, who line up either side of the net in groups of three. Perfectly in time with each other they cross the court, step over their mops and cross back again.

The challenge is "to have the mop perpendicular to the net, to keep in time with the other side and to read each other".

"It can go wrong, you can trip over the mops. But if you get two hands on it, it should be fine," she says.

The rest of the team retrieves the balls, keeping two in each corner and one in play.

"It's so important because if one of us loses focus, the whole game comes to a standstill, they would be looking for balls," she says.

"It is a fast game, rallies don't last long, you can't be sat about. You've got to be on the game all the time."

Paul Maines, arrow collection trainer, archery

Beijing 2008, and when the archers had shot, the arrows were returned to each competitor on a mechanical train.

It was fairly efficient, but it lacked the human touch.

The arrows travelled back to base in a special tube at Lord's

So at London 2012 three groups, each of eight volunteers, drawn from schools and archery juniors, were regimentally drilled.

As the archers shot successive waves of arrows, the judges recorded the scores, the arrows were removed from the targets, put in a special tube, given to the Gamesmakers and returned to their owners.

Each archer reused their own arrows, with different lengths and 'fletches' or 'vanes' - the feathers that stabilise the arrows in flight.

"We had to make sure consistency of approach, which way the collection volunteers turned, how they came back, how they presented them to the archers," says Paul. "The idea being the archers, coaches and judges got used to the same pattern.

"It's a very important part of the job, like the ball boys and girls of Wimbledon, they're the ball boys of archery."