The growing demand for food banks in breadline Britain

- Published

- comments

Newsnight's Paul Mason says as benefits are cut and rules tightened the food banks can expect to see a lot more people

More food banks are opening every week in the UK, with charities providing an emergency safety net for growing number of Britons, many of whom have fallen foul of the benefits system.

They say you can tell a poor area by the number of chicken takeaways. By that metric, Coventry, in the West Midlands, has more than its fair share of poverty.

Out of 306,000 people, according to the city council, 59,000 are living on the breadline. And with the UK economy in double-dip recession, the word breadline is starting to mean something literal.

"I've seen families sitting down to eat oven chips and mayonnaise as their main evening meal," says Mary Shine, a Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB) caseworker, "and that's people with children, and sometimes with health problems".

There is growing and documented hunger in Britain's poor communities. Unlike the chicken takeaways, and the payday loan stores, you cannot see it. But it is there.

Coventry is home to Britain's busiest food bank. Run by the Trussell Trust, it provides three days of good quality food for people who turn up, literally, hungry.

People (and quietly some supermarkets) donate food and it is given out to those referred by agencies dealing with poverty - social services, CABs, youth offending teams or churches.

Most people only use the food bank once or twice, after that the workers try to get them into a programme that addresses the root cause of the problem.

The Trussell Trust is launching new food banks at a rate of three per week.

But why, at a time when unemployment is falling, and house repossessions have never reached catastrophic levels, do we see agencies dealing with hunger?

Funds crisis

At the Coventry Foodbank, which operates out of a church called the Hope Centre, Martyne Wilson sits with her two toddlers and a four-week old baby, at her wits' end. What has brought her here?

"Benefit changes. The DWP [Department for Work and Pensions] are just not working fast enough to get my benefit sorted out, and I've been in crisis now for four weeks," she says.

She explains her teenage daughter moved back into the home, simultaneously with the arrival of her new baby, and when she added them to her claim for benefits, it failed. "It's not working out on the computer," she shrugs, giving a perplexed smile.

What does that mean in terms of food?

"It means I haven't got the money to go shopping, I'm just able to cover my bills and not get into debt at the moment," she says. "All I've got in the house is rice and some bread, I haven't got anything else in at all, and if I go to the DWP asking for crisis loans it's landing me in more debt."

"I think I'm hitting like the £900 mark now in debt, because of my benefits being stopped and started and just not knowing where I am with benefits at all."

Benefits 'sanction'

This it turns out is not unusual. The Trussell Trust reckons 43% of all those referred to the food bank are there because of benefit stoppage or the refusal of a crisis loan.

Usually that is because they have fallen foul of the conditions that require people on benefits to demonstrate they are looking for work, and have been, as the system puts it, "sanctioned".

Martyne Wilson says a change in the number of children in her household caused her claim to fail

"It is reasonable to expect people to apply for a certain number of jobs per week," says Gavin Kibble, who runs the Coventry food bank. "But if you fail that particular test and you have a sanction, the sanction could be there for weeks."

"Now the logic flaw in that is exactly where do you expect people to go and find money during that period if Jobseeker's [Allowance] is supposed to be the point of last resort in terms of income? Effectively we become a backstop to the welfare state system."

Martyne explains she is getting Child Benefit and Child Tax Credit for two of the four children in the house. So what stops her using that to buy food?

"Bills," she says. Her partner, Darren England, who is long-term disabled, spells it out: "Clothes, water bill, electric, TV licence."

And, chips in Steven McEnery, a family member, "she's already had to borrow from other people she knows who'll help out; so when she gets the money she has to pay them back".

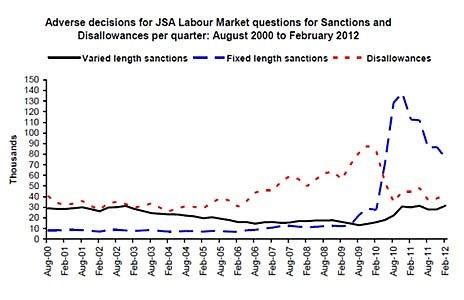

All cases in this mix of benefits, debt and food poverty are complex, but Martyne's predicament is becoming common and if you look at the Department for Work and Pensions graph below you can see why.

Since 2010, while the number of people getting their Jobseeker's Allowance (JSA) claims refused has fallen, from 80,000 to about 40,000, the number of people getting their benefits suspended has spiked.

And this is just for JSA. The controversial disability tests introduced for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) are leading to thousands of people having their disability benefits cut, sometimes by £30 out of £100 a week, says the CAB.

To put it bluntly, the new benefits regime is forcing people off benefits - not permanently, but as a temporary punishment. According to the Department for Work and Pensions, sanction or disallowance happened to 167,000 people, external in the three months to February 2012.

Debt trap

But if 43% of the hunger being dealt with by food banks concerns benefit disruption, where does the rest come from? How is it that people in work, or on full benefits, can end up hungry?

At the CAB in Coventry the answer stares them in the face each morning when they open the doors to a queue of people, often numbering their entire capacity for the day. It is debt.

Manager Gavin Kibble says the food bank has become a backstop to the welfare system

Mary Shine says she comes across food poverty three or four times a week in her home visits. Often people are prioritising paying interest on their debts over buying food.

A particular problem, says Ms Shine, is doorstep lending:

"Doorstep lending is always about preying on people who are unable to access High Street banks," she says. And adding to the problem is the way lenders befriend clients:

"It's not the man from the credit company, it is 'my friend Tom, who's been coming for years'," Ms Shine explains. "I think it's all about the befriending and then the guilt-tripping, the fear that you're letting them down."

"The result is they're paying £15, £10 a week to the doorstep lender out of their food bill."

The CAB says that when they try to help people manage their debts, it is common to find them so protective of doorstep loans that they do not want to renegotiate them, sometimes even walking away from debt counselling rather than upsetting the doorstep loan company.

Safety net

High interest lending to poor people is a boom industry now in Britain. That, combined with low wages and insecure work is what drives people with jobs to the food bank.

CAB caseworker Mary Shine says she sees three or four incidents of food poverty each week

And it is hard to see quick solutions: successive governments have shied away from capping the interest rates the payday loan and doorstep lending companies charge. Yet the prevalence of families prioritising debt over food is troubling.

With the benefit disruption problem, it has clear roots in the determination of successive governments to make it harder to stay on benefits long-term.

But whether by accident or design, the rise in JSA "sanctions" - together with recent changes to disability benefits - say the CAB, seems to correlate directly with the growing number of people who turn up at food banks.

The welfare system is creating a new kind of poverty, and the new safety net is not the state at all, but the volunteers sorting the tins and pasta at the Hope Centre and places like it.

Watch Paul Mason's report on food banks on Newsnight on Tuesday 4 September 2012 at 2230 on BBC TWO, then afterwards on the BBC iPlayer and Newsnight website.