Abu Hamza: What happens next?

- Published

- comments

Eleven years ago, Tony Blair was about to speak at the annual TUC conference when the world witnessed the 9/11 attacks on America.

The speech was cancelled - but very quickly the prime minister declared the UK would stand should-to-shoulder with the American people, against terrorism everywhere.

That declaration of support triggered a massive effort to bring British and American security operations closer together to hunt down anyone the two countries believed was involved in al-Qaeda-inspired violence.

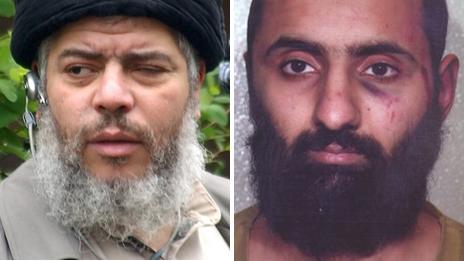

A great deal of that post 9/11 deal focused on extradition and how to bring men like the radical cleric Abu Hamza al-Masri to justice - men accused of supporting terrorism across international borders.

Abu Hamza could be extradited within weeks

Abu Hamza, a former nightclub bouncer, had seized control of a mosque in north London in the late 1990s and turned it into his powerbase for jihad. His band of followers included men from across the world - men whom the Americans said could be clearly linked to major terrorism plots.

And this is where the interests came together. The Americans knew who they wanted - and the British knew where they were.

The case against Abu Hamza is substantial. He faces 11 allegations including trying to set up a terrorism training camp in a remote region of Oregon. He is also alleged to have assisted in hostage taking in Yemen, an incident in which Western tourists died. If convicted, he faces life imprisonment.

Two of the other five are Saudi Arabian-born Khaled al-Fawwaz and Egyptian Adel Abdul Bary. They are accused of being key aides to Osama bin Laden in London. They allegedly played roles in the 1998 US embassy bombings in East Africa, in which more than 200 people were killed and thousands injured. Mr al-Fawwaz has been held in detention since 1998, four years after he arrived in the UK. Mr Bary was arrested and detained the following year.

Private prosecution

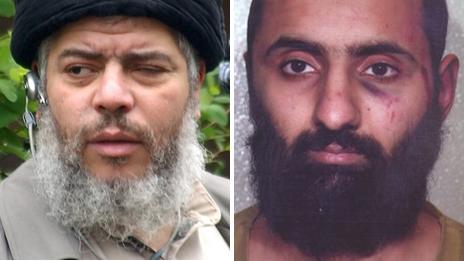

The most controversial cases are those of Babar Ahmad and Syed Talha Ahsan, Mr Ahmad, born and brought up in south London, has been in detention since 2004. No British citizen has been held for longer in the UK without trial.

He is accused of using a London-based website called Azzam.com to provide support for terrorism around the world.

His supporters say he should be tried in the UK because the American case against him relies on material seized by the Metropolitan Police in London. A businessman is trying to privately prosecute Mr Ahmad and Mr Ahsan, saying they should face British justice.

Many legal experts agree that the private prosecution has a slim chance of ultimately stopping those two extraditions. That's something that will become clear in the coming weeks.

But why has this process taken so long?

Babar Ahmad, 37, has been held in UK custody without trial for nearly eight years

The simple answer is that it was unprecedented. As the cases moved through the British courts, it became clear that there had to be a definitive ruling on whether US jail conditions and justice matched the standards that the UK adheres to through the European Convention on Human Rights.

The five cases slowly came together in Strasbourg, where top human rights judges (it's worth noting that they were until recently led by a British judge) wrestled with complex questions relating to inhumane treatment.

The two key challenges related to what can appear to some Europeans an extreme system in the US. Prisoners can get life sentences without any possibility of parole - the five men facing extradition in this case would not face the death penalty.

Four of the five could face near total solitary confinement for years in ADX Florence, a "supermax" jail used to hold the most dangerous men in the country. Abu Hamza is unlikely to go to that prison because of his disabilities.

Security questions

The court has now ruled that America's standards are compatible with European human rights. That means that any European nation receiving an extradition request from the US, in similar circumstances, can provide the suspect with far less delay - certainly less than a decade.

So the wheels of extradition are now turning. Department of Justice officials will begin talking to their London counterparts in the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice about how the men will be handed over.

Typically, an extradition happens within two weeks of a final appeal being turned down.

These cases may take a little longer to process. The US, for instance, will need to work out what facilities it is providing for Abu Hamza, given his disabilities.

There is also the security question. Each man is considered a high-risk detainee. We don't know yet how the US wants to transfer the men, whether on one flight - which would have enormous symbolic value to British ministers - or separately and with no fanfare.

Once they arrive in the US, the men will be transferred to courts in New York and neighbouring Connecticut where the formal trial process will begin. They will be given lawyers and the same rights as other defendants.

- Published24 September 2012

- Published5 October 2012