Big Issue magazine marks 21st anniversary

- Published

The Big Issue began in London in 1991 and now has Scottish, English and Welsh editions

The Big Issue, which is celebrating its 21st anniversary, has become a regular fixture on the UK's streets. But how has the magazine - and its impact on people's lives - changed during the past two decades?

Terry Gore is a busy man. His days are filled trying to help people of all ages with their problems.

Terry runs a day centre for homeless people in Canterbury and works part-time as a counsellor in a school.

But his sense of altruism could stem from the fact that he spent much of his life struggling with his own personal demons.

In the early and mid-1990s Terry was a homeless alcoholic and, by his own admission, lived a "chaotic lifestyle".

He says The Big Issue magazine helped him to transform his life.

The weekly publication, which was first sold by homeless people in 1991 before spreading to other parts of the UK, operates by selling the magazine to vendors for half the cover price. They then get to keep the difference when they sell the magazine on.

Back in 1991 it cost readers just 50p, now it is £2.50.

And there are now editions in the north and south-west of England, as well as Wales and Scotland.

"I was drinking all the time and the magazine gave me structure. It allowed me to earn money. It gave me back my self-respect and got me back in touch with people," Terry told BBC Breakfast.

"I was committing crimes to fund my alcoholism. Mostly shoplifting. I used to re-sell travelcards at rail stations, which is a criminal offence.

"It was another two-and-a-half years before I got off the streets."

The sight of a homeless person selling magazines is now common. But two decades ago it was a new idea.

The magazine's founder, John Bird, remembers the initial difficulties in starting the publication.

"The big problem we had to face was the fact that we were giving people with severe problems the opportunity to make money," he recalls.

"People were saying they were only going to spend it badly.

"I said, 'yeah, but at the moment they are begging, they are breaking into cars in order to do something to harm themselves. Wouldn't it be better if you decriminalised them and then tried to sort them out'."

Since then, the magazine has raised about £150m.

"Wherever we've tried it, the first people to pat us on the back are the police. They say you're taking people who are full of grief, and they're causing grief to other people, and you're decriminalising them. They said: 'Great, marvellous'."

Mr Bird says the secret behind the magazine's success is to create a product with an appeal that extends beyond the founding remit of helping homeless people "to help themselves".

"In the beginning I thought that if you had a magazine that was full of homeless stories, nobody would want to read it beyond the second or third issue. I thought you had to have a magazine that people were proud to sell and people were pleased to buy.

"If you buy something from me that you don't really want, the relationship is uneven."

By selling something that readers want, homeless people can be seen as equals, he says.

Vendor rule change

Meanwhile, The Big Issue Foundation, a registered charity, attempts to connect vendors with the vital support and services in housing and health, as well as trying to foster a sense of financial independence and aspiration.

It relies almost entirely on voluntary donations.

Over the years the magazine has been championed by a raft of celebrities such as Stephen Fry and actor Ewan McGregor.

But it has not been entirely free of controversy.

Two years ago the decision to introduce vests sponsored by a wine producer prompted criticism from those who feared it clashed with the fact that many vendors had struggled with some form of addiction at some point in their lives.

And last year the publication faced accusations that its message had been diluted after it changed its rules so that it could be sold by unemployed people, as well as the homeless.

At the time, London vender Mahesh Pherwani, told the BBC: "I do not see it as competition - we are all in the same boat.

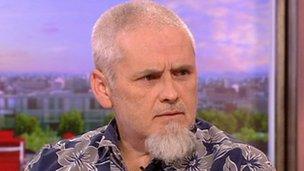

Terry Gore says The Big Issue helped him to transform his life

"But it will have an impact on people's perception of how The Big Issue operates and what it exactly represents."

Mr Bird, who argued that the move reflected the tough economic climate, said the publication did not want to see people "slip into long-term unemployment and homelessness" and wanted to help wherever possible.

The charitable organisation currently supports 2,900 people, while the magazine and its weekly circulation is currently more than 105,000 copies.

In England there were 12,860 households from April to June 2012 which were statutorily homeless - they meet specific criteria which means they need to be helped by a local authority.

Such households are rarely homeless in the literal sense of being without a roof over their heads, but are more likely to be threatened with the loss of their current accommodation.

In Wales there were 1,445 such households from April to June 2012, in Scotland 8,853 up to March, and 9,021 in Northern Ireland.

Homeless charity St Mungo's says The Big Issue "proves that with the right support, people can and do successfully build a life away from homelessness".

"St Mungo's believes that homeless people need a second chance to get skills and a job," said its executive director of operations, Mike McCall.

He says about two thirds of St Mungo's residents have been unemployed for more than five years and only 4% are in permanent employment.

"Clients want to work but many have low levels of literacy and often lack the basic skills required to get them into work. They require specialist support to enter the job market," he says.

Meanwhile, The Big Issue's founder accepts that the publication, and its charitable foundation, cannot help every homeless person.

"I would say that we can really help 20%, we can almost help another 20% and the rest might be with us forever," he says.

And that is a sentiment that is echoed by Terry.

"The magazine helps a lot of people but there are a lot of people out there that it can't help because they don't have the basic structure and self-esteem to get up there and do that in front of people."

- Published14 July 2010