Dignity sought in Mau Mau ruling

- Published

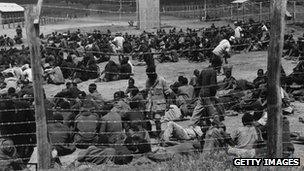

The case has taken six decades to come from Kenya to the High Court

The ruling on Friday in the High Court is a key moment in what has been a long legal battle against the UK government.

The three Kenyans - two of whom are in their mid-80s - claim to have been tortured by British colonial authorities during the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s.

After court proceedings lasting less than five minutes, the judge Mr Justice Richard McCombe ruled that despite the years that have passed a fair trial was possible.

Paul Nzili, Wambugu Wa Nyingi and Jane Muthoni Mara can now pursue their case. They are seeking an apology and recompense for the abuse they suffered while in detention during the conflict.

Their lawyers have always said the Kenyans want to be able to live out their final years with a degree of dignity, and are determined to obtain justice.

State of emergency

The story began exactly 60 years ago when the Mau Mau, or the Kenya Land and Freedom Army as they called themselves, claimed their first European victim.

A woman was stabbed to death near her home in Thika.

On 20 October 1952, Kenya's Governor Sir Evelyn Baring declared a state of emergency amid the growth of the Mau Mau movement.

So began one of the darker periods of British colonial history.

The Mau Mau waged a violent campaign against white settlers in Kenya.

A frequent question is why the claims of torture have taken so long to emerge.

This can be partly explained by the fact that the Mau Mau movement remained banned in Kenya until 2003, 40 years after independence.

Under Kenya's founding father, Jomo Kenyatta, and later during the administration of President Daniel arap Moi, the Kenyan government did little to help Mau Mau victims.

Kenyatta was a strong nationalist, but he was not a member of the Mau Mau and tried hard to bury the past when he became president.

The Mau Mau was therefore something of a taboo subject in Kenya until President Mwai Kibaki was elected head of state and allowed the veterans to register as a legal society.

'Genuine case'

The Kenya Human Rights Commission says the current administration's support for the three claimants has been largely verbal, but appreciated nonetheless.

In July, Prime Minister Raila Odinga told a Kenyan radio station "the claimants had a genuine case in seeking compensation and a statement of regret for the treatment they suffered".

After attacking white settlers in Kenya, the Mau Mau were captured and tortured

Another reason why the case only came to court after so many years is that some of the history of the Kenyan Emergency was revealed by academic research conducted as recently as 2005.

Even now, the Hanslope Archive of some 8,800 secret files, sent back to the UK at the time of independence, has yet to be made public, although the documents were referred to at the High Court in London.

Leigh Day and Co, the lawyers who have brought the case against the British government, claim there are also files relating to 36 other colonies that have been discovered.

David Anderson, professor of African studies at Oxford University, says there are two distinct features about the Kenyan torture case.

First, there are victims still alive, and second, none was ever convicted of any crime or charged.

Cause for concern

But Prof Anderson warns that there are other episodes of British colonial history that may give the Foreign and Commonwealth Office cause for concern in the wake of this Kenyan legal saga.

They are Cyprus, Malaya and Aden, although he says that what happened there, was "not on the same scale or intensity as Kenya".

The British government conceded in court in July that torture had taken place in Kenya in the 1950s.

The Foreign Office says it is disappointed with the latest judgement and will appeal.

However, a Foreign Office statement on Friday said: "We do not dispute that each of the claimants in this case suffered torture and other ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration."

A full trial could still be a year away. lt will need to rely heavily on documentary evidence rather than witness statements because of the years that have elapsed.

In the meantime, lawyers for the Kenyans remain hopeful that the British government might agree to an out-of-court settlement.

This would involve a welfare scheme to assist the elderly Kenyan victims with their health needs.

- Published5 October 2012

- Published5 October 2012

- Published17 July 2012

- Published7 April 2011

- Published6 April 2011