Cambridge Spies: MI5 diaries revealed

- Published

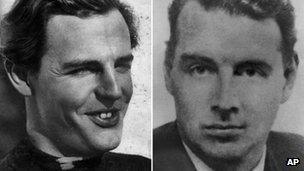

The diaries detail the disappearance of Cambridge Spies Donald Maclean, left, and Guy Burgess, right

The diaries of former deputy MI5 chief Guy Liddell provide a unique insight into the Security Service during some of the darkest days for British intelligence.

The diaries, made available online from the National Archives on Friday, cover the period when evidence emerged of the treachery within the British establishment in the form of the men - who would become known as the Cambridge Spies - who had spied for the Soviet Union.

Liddell provides a day-by-day account of the unfolding drama, while the diaries' matter-of-fact writing style barely conceals how personal the betrayal was for the MI5 man who was close friends with some of the key protagonists and who struggled to believe what they had done.

"It was an age of treachery," explains Stephen Twigge of the National Archives. "His whole world was falling apart around him and it is all there in the diaries."

In early 1951, Liddell notes that evidence has come in suggesting Foreign Office man Donald Maclean may be a Communist spy.

The investigation begins with "watchers" put onto him.

On 18 May there is reference to a meeting planning his interrogation. But just as the net is closing in - he vanishes.

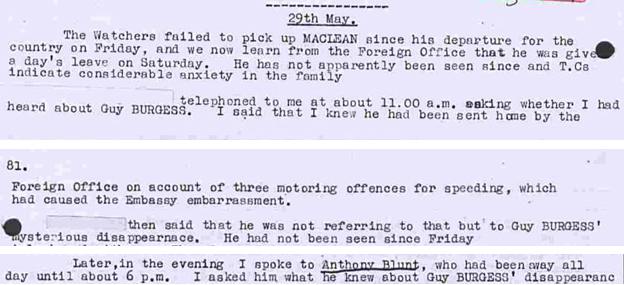

29 May 1951

The watchers failed to pick up Maclean since his departure for the country on Friday and we now learn from the Foreign Office that he was given a day's leave on Saturday. He has not apparently been seen since...

(NAME REDACTED) telephoned me at about 11am asking whether I had heard about Guy Burgess. I said that I knew he had been sent home by the Foreign Office on account of three motoring offences for speeding, which had caused the embassy embarrassment.

(NAME REDACTED) then said that he was not referring to that but to Guy Burgess' mysterious disappearance. He had not been since Friday...

The two had gone to Moscow together, although MI5 has no idea as a frantic search is detailed.

The departure of Burgess comes out of the blue and is a shock, particularly for Liddell.

The Foreign Office man had been a friend of Liddell's for many years and the two had regularly visited the musical hall together, according to Andrew Lownie, author of Stalin's Englishman - an upcoming biography of Burgess.

"That is one of the tragedies of this story," Mr Lownie told the BBC.

"Liddell was a very devoted public servant. He must have felt a great sense of personal betrayal."

The diaries show Liddell dealing with the fallout from Burgess' various debauched adventures in previous years, but he struggled to comprehend that his friend could be allied to Maclean and that the two might have voluntarily gone to Russia.

The question emerges - how did the two learn about the investigation into Maclean?

Perhaps the man in whose house Burgess was living in Washington might have an idea? It might be worth talking to that man - Kim Philby, MI6 station chief in Washington - Liddell notes in the diary.

12 June 1951

Dick had a long interview with Kim Philby who had arrived from Washington at 2.30 today.

Personally I think it not unlikely that the papers relating to Maclean might have been on Kim's desk and that Burgess strolled into the room while Kim was not there.

The story of the Cambridge Spies was told in a 2003 BBC drama of the same name

The truth was much worse.

Soon other pieces of the jigsaw are put together and the possibility that Philby is another Communist spy takes hold within MI5.

On 4 August, there is a scare when they learn he is going yachting and fear he will flee.

The Americans are also convinced he has gone bad and say they do not want him back in Washington - concern over what the Americans think is a recurring theme.

The problem is a lack of evidence. By December, the prime minister is making clear he wants Philby interrogated.

The diaries include feedback from Philby's first interrogation in which the interviewer comes away convinced of his guilt but unable to prove anything.

But it was not just Philby.

One of the first people Liddell contacts on the day he learns of Burgess and Maclean's disappearance is his friend, the former MI5 officer Anthony Blunt.

The diaries are full of accounts of "lunch with Anthony" or "dinner with Anthony".

Blunt is called on for advice, since he knew Burgess and Maclean at Cambridge.

What Liddell does not know is that the young student, Burgess, had recruited the older Blunt into the spy ring.

"I feel certain that Anthony was never a conscious collaborator with Burgess in any activities that he may have conducted," Liddell writes in the diary.

Blunt has now become the King's surveyor of pictures. At one point the diary recounts the King's private secretary, Tommy Lascelles, coming to see Liddell about Blunt for reassurance.

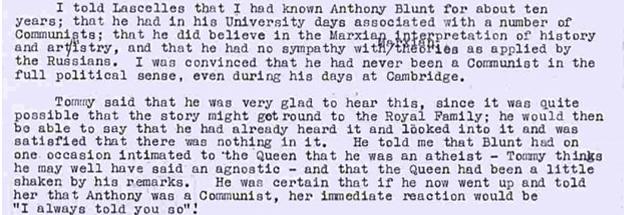

13 July 1951

I told Lascelles that I had known Anthony Blunt for about ten years... I was convinced that he had never been a Communist in the full political sense, even during his days at Cambridge.

Tommy said that he was very glad to hear this, since it was quite possible that the story might get round to the Royal Family; he would then be able to say that he had already heard it and looked into it and was satisfied that there was nothing in in it.

He told me that Blunt had on one occasion intimated to the Queen that he was an atheist - Tommy thinks he may well have said an agnostic - and that the Queen had been a little shaken by his remarks.

He was certain that if he now went up and told her that Anthony was a communist, her immediate reaction would be "I always told you so".

The diaries also show that MI5 was on to John Cairncross as the fifth man of the Cambridge Spy ring by 1952.

Kim Philby fled to Moscow in 1963

"He was extremely perturbed when confronted with the document in his own handwriting which had been found among the papers of Burgess," Liddell writes.

MI5 watchers see him throwing away a recent copy of the Communist Review into a park paper bin.

The diaries show MI5 had successfully identified the spies but lacked the evidence to do much about it.

Philby's name would leak as "the third man" in 1955 but he would deny it until he fled, in 1963, to Moscow.

Blunt confessed to MI5 in 1964 but the public only learnt of what he had done in 1979, around the same time as they learnt of Cairncross.

And what of Liddell himself? The diaries include his account of an interview for the top job at MI5.

He missed out on it. Partly, it is thought, because of suspicions created by his friendships.

The diaries show he was certainly no traitor - just an MI5 man trying to do his best but suffering under the weight of some dangerous friendships in treacherous times.