Abu Qatada released from prison

- Published

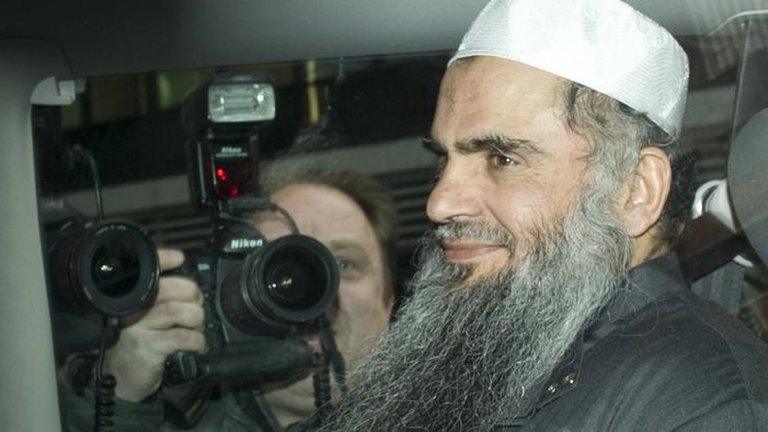

Abu Qatada being driven out of Long Lartin prison after his release

Muslim cleric Abu Qatada has been freed on bail after a UK court ruled he might not get a fair trial if deported to Jordan to face terrorism charges.

He was released from Long Lartin prison, in Worcestershire. He has spent most of the last 10 years in custody.

A UK court approved his appeal against deportation after deciding witness evidence obtained by torture might be used at trial in Jordan.

The government believes the wrong legal test was applied and is to appeal.

"We had received a number of assurances from the Jordanian government - they had even changed their constitution," a spokesman for Prime Minister David Cameron said.

"We believe that we have got the right assurances from the Jordanian government."

He added: "The Home Office will be ensuring that we take all the steps necessary to ensure that Qatada does not present a risk to national security."

Jordan's acting information minister Nayef al-Fayez told the BBC his government shared UK authorities' disappointment at the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (Siac) ruling on Monday.

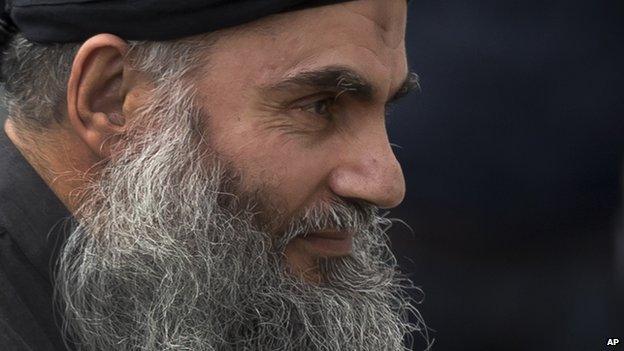

When Abu Qatada arrived back at his home in London, around lunchtime on Tuesday, a small group of protesters - holding a "get rid of Abu Qatada placard" - gathered outside and chanted, "Out, out, out."

Earlier this year, judges at the European Court in Strasbourg ruled the cleric - whose real name is Omar Othman - would not face ill-treatment if returned to Jordan, citing assurances outlined in a UK-Jordan agreement.

Crucially, however, the judge did not believe he would get a fair trial because a Jordanian court could use evidence against Abu Qatada that had been obtained from the torture of others.

On Monday, despite the UK obtaining additional assurances from Jordan, Siac chairman Mr Justice Mitting ruled he was not satisfied Abu Qatada would be tried fairly.

'Act fast'

Speaking to ITV's Daybreak, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg said: "He should not be in this country, he is a dangerous person. He wanted to inflict harm on our country and this coalition governs lived in the UK for almost 20 years - and he might be here a few more yet because the legal roadblock on deportation is very difficult to remove.

Judges say there is a real risk that the preacher's retrial in Jordan would be unfair because it would include incriminating statements made by men who were tortured by the secret police.

Abu Qatada was born in Bethlehem in 1960 and spent his early life in Jordan. He fled to Pakistan in 1989 claiming political persecution and eventually arrived in the UK in 1993. Abu Qatada was part of a wave of Islamists who sought refuge in the UK during the 1980s and 90s, often exiled from the Arab regimes they were trying to overthrow.

Abu Qatada emerged as a key voice in the Islamist movement in London, which advocated strict Islamic government in Muslim countries and armed struggle against despots and foreign invaders. His preachings and ideas won him influence among Islamist groups in Algeria and Egypt during the 1990s. He was tried and found guilty in his absence of terrorism offences in Jordan in 1999.

By 2001 fears were growing about Abu Qatada's hard-line views. He endorsed suicide attacks in a BBC interview and was questioned in connection with a German terror cell. Copies of his sermons were found in the Hamburg flat used by some of the 9/11 attackers and Spanish judge Balthazar Garzon described him as the "spiritual head of the mujahideen in Britain". In December 2001, Abu Qatada disappeared and became one of the UK's most wanted men.

In October 2002 Abu Qatada was arrested and detained without charge. He was released in 2005 and put under strict house arrest, but months later was arrested under immigration rules and moves began to deport him to Jordan to face retrial on the charges he had been convicted of six years earlier. In 2007 he lost his immigration case, but the Court of Appeal later ruled that deportation to a regime which uses torture - ie Jordan - would breach his human rights.

The Court of Appeal ruling was overturned by the Law Lords in early 2009, and the then Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith (L), signed a deportation order. Abu Qatada then appealed to the European Court, which eventually ruled that he could not be deported while the risk of torture remained. In 2012 Home Secretary Theresa May (R) pressed ahead with deportation, but this was blocked amid a row over the appeal deadline.

In November 2012 Abu Qatada was released from prison once more after a UK court backed his appeal on the grounds that witness evidence obtained by torture could be used against him at trial in Jordan. That was a disastrous blow to the Home Office because it meant the only way the deportation could happen would be if Jordan changed its system to ensure torture-tainted evidence could not be used.

Abu Qatada was then returned to prison on 9 March 2013 after an alleged breach of his bail conditions - but this deportation was still blocked. Weeks later, Home Secretary Theresa May announced a new UK-Jordan treaty to improve co-operation in criminal investigations. That treaty included a guarantee of a fair trial free of torture-tainted evidence for anyone sent back to Jordan. Abu Qatada's lawyers announced he would now return to Jordan.

Shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper said people would be "horrified that Abu Qatada is now out on Britain's streets rather than on a plane", and that government efforts to secure his deportation had "clearly failed".

"Home Office ministers should be setting off to Jordan straight away to discuss what additional action would get this sorted out. The Jordanian government have already been very helpful so ministers should act fast," she said.

Criminal code

David Anderson QC, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, told the BBC: "The key to this case really lies in Jordan.

"What the judge said, what the court said in terms, was that a simple amendment to the Jordanian criminal code so as to remove an ambiguity that is in it at the moment ought to suffice to make deportation possible," he told Radio 4's Today programme.

Home affairs committee chairman Keith Vaz said the visit to the UK of the king of Jordan later this month gave the government "an opportunity to try and persuade him to go that little bit further in terms of the way the criminal code of Jordan operates".

The case had cost taxpayers £1m, he said.

Human rights lawyer Julian Knowles said the case would bring "another year's worth of UK litigation at least".

"And then if Abu Qatada is the loser at the end of the domestic phase, he can then go back to the European Court," he said.

Speaking in the Commons after Abu Qatada's release, Justice Secretary Chris Grayling said he was "frustrated" by international court rulings that had led to Monday's decision.

"I do not believe it was ever the intention of those who created the human rights framework that we are currently subject to, that people who have an avowed intent to damage this country should be able to use human rights laws to prevent their deportation back to their country of origin," he added.

On the question of why Abu Qatada had never been prosecuted in the UK, Lib Dem peer Lord Macdonald - director of public prosecutions from 2003 to 2008 - said he had never been shown any evidence to support a criminal prosecution.

"If there isn't any evidence in existence at the moment, it's a little difficult to see how now, 10 years later, anyone is going to be able to acquire any," he told Radio 4's The World At One.

The bail conditions imposed by Mr Justice Mitting on Abu Qatada include being allowed out of his house only between 08:00 and 16:00, having to wear an electronic tag, and being restricted in whom he meets.

Abu Qatada faces a retrial in Jordan for allegedly conspiring to cause explosions on Western and Israeli targets in 1998 and 1999. He was found guilty of terrorism offences in his absence in Jordan in 1999.

The Palestinian-born Jordanian has been described as the spiritual leader of the mujahideen. Security chiefs believe he played a key ideological role in spreading support for suicide bombings.

- Published13 November 2012

- Published26 June 2014

- Published12 November 2012

- Published12 November 2012