2011 Census: Is Christianity shrinking or just changing?

- Published

Numbers of nominal Christians are declining despite the close links between Church and state.

The response from some Church leaders to the latest census figures has been to describe them as "challenging".

Churches had pointed to the 72% of people who described themselves as Christian in the 2001 Census to help justify their claim that Britain is a "Christian country".

The sharp decline in the number of people in England and Wales identifying themselves as Christian to 59% is a sign of the religion's weakening influence in society.

The secular trend is confirmed by the significant increase in the percentage of people describing themselves as having no religion from 15% to 25%.

But the churches say they are not discouraged, claiming that Christian belief is still clearly alive and well.

It is true that the raw figures hide a far more complex story, both about Christianity and secularism.

By asking people to state their religion, or lack of it, the census was asking a complex question.

But it allows only a one- or two-word answer, obscuring almost as much as it reveals about what has happened to religion during the past decade.

Religion is about more than belief. It can be a badge of identity, an inheritance of upbringing or a statement of moral intent.

It was always clear that the 72% who said they were Christian in 2001 were by no means all churchgoers signed up to all of standard church teaching.

At the same time, according to academic researchers, many of those who said they had no religion still shared some religious beliefs and more general "spirituality".

For several decades the boundaries between Christianity - as the mainstream, or default - religion in England and Wales, and "no religion" have been blurring.

Sense of identity

By the time of the last census they were probably more porous than ever, reflecting fundamental change, as much as decline, in religion.

Christian organisations insist that the census measured a sense of identity rather than belief.

The Christian research group Theos claims that "even amongst atheists, the most sceptical group in the population, nearly a quarter (23%) believe in the human soul, 15% in life after death, and 14% in reincarnation".

The National Secular Society described the census figures - four million fewer people describing themselves as Christians - as a "major reverse for Christianity".

The society's president, Terry Sanderson, said "It should serve as a warning to the churches that their increasingly conservative attitudes are not playing well with the public at large.

"It also calls into question the continued establishment of the Church of England whose claims to speak for the whole nation are now very hard to take seriously."

Certainly an estrangement from institutions seems to account for at least some of the shift.

Fuzzy faith

Once - had you gone to a hospital casualty unit with a cut hand and been asked routinely what your religion was, and answered, "Well, none really" - the receptionist might have helpfully suggested, "Let's put you down as C of E."

That role has suffered as nominal Anglicans re-evaluate their relationship with a body whose traditional teaching on sex and gender has seemed out of step with secular priorities such as equality.

Even the term "religion" has become associated in some people's minds with extremism and oppression.

"Christianity" has for many people become an increasingly ill-defined practice, incorporating a wider array of spiritual aspirations and beliefs.

This "softer" and more fuzzy form of faith no longer dictates how people behave, who their friends are or how they vote.

Perhaps as people now look at their eclectic views, their personal collection of beliefs and spiritual practices, and realise how little it fits with any church, they are more ready to declare themselves to be of "no religion".

But churches say those who do choose Christianity do so wholeheartedly.

Members of other religions are heeding calls to declare themselves

As the Roman Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales put it: "Christianity is no longer a religion of culture but a religion of decision and commitment.

"People are making a positive choice in self-identifying as Christians."

During a decade in which the Christianity taught by mainstream churches seems to have faded from people's lives, non-Christian religions have gained members.

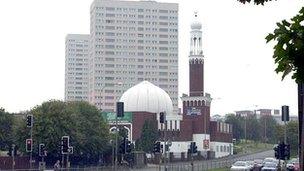

The increase in the number of Muslims is particularly marked, up from 3% to almost 5% of the population.

But there were more Hindus, Sikhs and members of smaller groups such as Spiritualists.

The increasing numbers identifying themselves with non-Christian religions seem partly the result of migration and higher relative birth-rates.

But they are also explained by a number of campaigns encouraging members of minority faiths to acknowledge their religions, assuming that the bigger their numbers prove to be, the more influence they will have.

Hindus are, for example, keen to break free of their joint labelling with other religious groups as "Asians".

In another sign of changing patterns of faith, Pagans - who have achieved some recognition as a religion since the last census - recorded a membership of 57,000 people.