The Nazi prisoners bugged by Germans

- Published

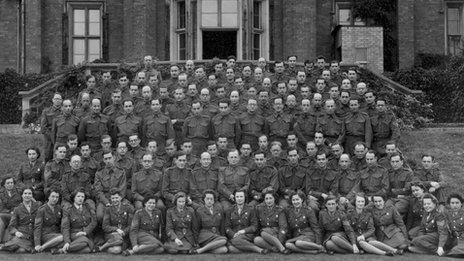

A secret listener at Trent Park, one of a team of about 100 German men

Thousands of German POWs held captive in England during World War II were bugged by "secret listeners" who were themselves German refugees, working for the British. Historian Helen Fry and one of the last surviving listeners explain how the prisoners were lulled into divulging secrets of the Nazi war machine.

One group of German generals captured during World War II thought they had hit the jackpot.

Held in a stately home, they were allowed to keep personal servants, drink wine and eat good food.

As a result they boasted of how stupid the British were, and one even wrote to his family to wish that they could join him at his prison, as he rated it so highly.

But what the prisoners did not know was that British intelligence had bugged every part of their accommodation, from lampshades and plant pots right down to the billiards table around which they relaxed on lazy days.

They were gleaning information about the psyche of the Nazi military from the idle gossip flowing between the prisoners.

Fritz Lustig spent many hours secretly listening to Germans POWs

Carefully listening in on their conversations were fellow Germans of Jewish origin who had fled from the Nazis.

The bugged prisoners were kept in three locations - Latimer House near Amersham, Wilton Park near Beaconsfield, both in Buckinghamshire, and Trent Park near Cockfosters in north London. The first two held captured U-Boat submarine crews and Luftwaffe pilots, who were bugged for a week or two before being moved on to conventional captivity.

The generals, whose numbers eventually reached a peak of 59 as the war progressed, resided in Trent Park until the war ended.

Hidden nearby in each of the three stately-homes-turned-prisons were the pro-British Germans, listening in a place known as the "M room" - the "m" stood for microphoned - where "secret listeners" were glued to the bugging devices.

Historian Helen Fry, who has written a book called The M Room: Secret Listeners who bugged the Nazis., external, says the information gleaned by the eavesdropping of the German generals was vitally important to the war effort - so much so that it was given an unlimited budget by the government.

Trent Park was home to 59 German generals during World War II

She believes what was learned by the M room operations was as significant as the code-breaking work being done at Bletchley Park.

"British intelligence got the most amazing stuff in bugging the conversations. Churchill said of Trent Park that it afforded a unique insight into the psyche of the enemy. It enabled us to understand the mind-set of the enemy as well as learn military secrets.

"If it wasn't for this bugging operation, we may well have not won the war."

Mrs Fry said the conversation transcripts, which numbered more than 100,000, provided the British with "most of what we knew" about Germany's military capability, its weaponry and its new development of technology during the war.

Through intelligence pieced together from prisoner conversations, the British were able to identify and heavily bomb a V2 rocket site in May 1943 at Peenemunde on the northern coast of Germany, which was preparing to launch deadly rockets at Britain.

Crucially, she adds, the bugging was the first time the British overheard admissions that the German army had taken part in the atrocities and mass killing of Jews and were guilty of war crimes.

"The army had always denied it and that was believed for the last 65 years. What the transcripts show us now is that the German army - with the SS - was complicit in war crimes," she says.

Apart from comfortable living arrangements, the Trent Park generals enjoyed such luxuries as garden parties hosted by Colonel Thomas Kendrick, the MI6 officer who oversaw the entire bugging operation and who later received an OBE for his efforts.

The high-ranking guests chatted away at such events in their native language, unaware that Col Kendrick himself spoke German and that such entertainment was being provided so as to relax them in captivity, making them so unguarded as to spill secrets - which they did.

Mrs Fry also says Winston Churchill was outraged when he learned the generals had been bussed into the lavish Simpson's-in-the-Strand in central London for lunch. He ordered what he called "the pampering of the generals" to be stopped.

But spoiling the generals and boosting their egos was providing so much useful information that the British intelligence officers decided to carry on, and simply stopped telling Churchill about it.

"The generals felt they were being treated according to their status." Mrs Fry said. "One of them wrote home to his family and said 'I really wish you could be here, it's wonderful - but without the barbed wire'.

"They had a British welfare officer who once a week would go into London and buy them shaving cream or socks or whatever they wanted. He was called Lord Aberfeldy but he wasn't a peer at all - he was an intelligence officer.

"But the British thought the generals would be flattered by being looked after by a lord."

Some of the captured German generals are seen here at Trent Park

There are thought to be only two "secret listeners" left alive from an original group of about 100. One of them is Fritz Lustig, 93, who lives in Muswell Hill, north London.

Although born in Berlin and baptised a Protestant, his family had Jewish members and so in the eyes of the Nazis he was "not Aryan enough" and left for England in April 1939.

Eager to help fight the Nazis, he eventually joined the British army's Royal Pioneer Corps and, as he was able to speak English, was transferred to the intelligence corps to become a secret listener.

Mr Lustig and other secret listeners were told on their first day by Col Kendrick that "what you will be doing here is more important than firing a gun in action".

"Morale was high among us," Mr Lustig says, "particularly if we had been able to gather something important. Emotionally, we were completely detached from the people we listened to."

He says he can no longer recall prisoner conversations, but does remember marking a transcript with "atrocity" in a red pen at one point.

"We listeners didn't feel that the prisoners were our fellow countrymen any more. We knew of all the horrible things that were happening in eastern Europe, with the killing of Jews, and we knew that would have happened to us if we had stayed in Germany.

"We felt no guilt - on the contrary, we felt proud to be able to contribute to the British war effort. I'm proud of what we did."

Almost all the men in this image, of Latimer House's staff, were secret listeners

Fritz Lustig was interviewed by the BBC World Service programme Witness. Listen back via iPlayer.